|

| Home | Articles | The Call of the Coast: Art Colonies of New England |

|

|

|

Art Colonies of New England

|

|

by Thomas Denenberg, Amy Kurtz Lansing, and Susan Danly

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Frederick Childe Hassam (1859–1935),

The Ledges, October in Old Lyme, Connecticut, 1907.

Oil on canvas, 18 x 18 inches.

Florence Griswold Museum; gift of the Hartford

Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (2002.1.66).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902),

Horseneck Falls, Greenwich,

Connecticut, ca. 1890–1900.

Oil on canvas, 25-1/4 x 25-1/4 inches.

Florence Griswold Museum; gift of the Hartford Steam

Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (2002.1.145).

|

The coast of New England has long attracted tourists drawn to the primal drama of wave on rock or the soothing play of glasslike ocean greeting sandy shore. The coast is historic, animated in the popular imagination by founding myths of the American colonies and legends of heroic maritime culture. It is timeless, populated by hardy individualists seemingly immune to change. No one place or geographic feature, the coast of New England is a varied and ever-changing landscape that has been both muse and home for artists working in the region's storied art colonies.

The call of the coast proved especially attractive to artists who placed their skills in service of the new culture of summer at the turn of the century. Seascapes—romantic visual dramas of sailing vessels tossed on the rocks or quiescent harbors brimming with commerce—enjoy a lineage that dates to the seventeenth century and remain in vogue to this day. In the course of the nineteenth century, however, images of the coast took on a nuanced and privileged importance in American visual culture. Whereas certain painters such as Winslow Homer sought solitude—indeed his reputation as the "hermit of Prouts Neck" is now the stuff of legend—the vast majority of painters, printmakers, and photographers who followed the tourist path to New England on railroads and steamship lines preferred company. Banding together for the purposes of camaraderie, creativity, and commerce, they founded art colonies from Connecticut to Maine.

The exhibition Call of the Coast: Art Colonies of New England examines four creative locales: Old Lyme and Cos Cob, Connecticut, and Ogunquit and Monhegan, Maine. In each spot, influential figures such as Childe Hassam (Fig. 1), John Henry Twachtman (Fig.2), Robert Henri, and Hamilton Easter Field fostered collegiality and inspired their students and followers to tackle the landscape with fresh, independent approaches. Each colony offered artists the opportunity to commune with the coast in its different guises, from rolling pastures by Long Island Sound to the elemental rocky terrain of Maine. The resulting artworks suggest the atmosphere of their places of creation: flickering impressionist renderings conjure Connecticut's calm shore, while bolder textures and expressive forms announce Maine's rugged landscape.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Henry Ward Ranger (1858–1916),

Long Point Marsh, 1910. Oil on canvas, 28 x 36 inches.

Florence Griswold Museum; Purchase (1976.5).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Edward F. Rook (1870–1960),

Laurel, ca. 1910.

Oil on canvas, 40-1/4 x 50-1/4 inches.

Florence Griswold Museum; gift of the Hartford Steam

Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (2002.1.117).

|

Arriving in Old Lyme by train in 1899, Henry Ward Ranger (1856–1916) spied France on the Connecticut shore. "It looks like Barbizon, the land of Millet. See the knarled [sic] oaks, the low rolling country. This land has been farmed and cultivated by men, and then allowed to revert back to the arms of mother nature. It is only waiting to be painted," he would later say.1 Part of the area's perceived charm was the record of human presence Ranger saw inscribed in the landscape—an aura of history and tradition that would flavor paintings by members of the art colony Ranger went on to found in Old Lyme (Fig. 3).

The quiet impress of man that Ranger admired accounted for much of the appeal of the Connecticut coast to artists venturing out by train from New York City. The village of Cos Cob, site of the state's other major art colony, offered century-old houses, a pocket-size harbor, and small farms—a far cry from the bustling streets of the turn-of-the-century metropolis (Fig. 2). The artists who painted in Old Lyme and Cos Cob delighted in the preindustrial atmosphere of these places, with their colonial architecture and cultivated landscape. Artists found these historic pastoral settings ideal for immersing themselves in nature through walks in the fields or along the shore, both opportunities to experience the outdoors on an intimate scale impossible in the city (Fig. 4). The quiet voice of the Connecticut landscape drew artists into conversation with its subtle qualities, a discourse sustained through the establishment of colonies in Old Lyme and Cos Cob.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Clarence Chatterton (1880–1973),

Road to Ogunquit, ca. 1940.

Oil on Masonite, 24-5/8 x 31-1/2 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine; gift of Pendred E. Noyce (1997.3.2).

|

If Ranger identified Old Lyme as an ideal spot for artists to gather, it was Florence Griswold who made the community an art colony. "Miss Florence," the only remaining member of an illustrious family whose ancestors included governors of Connecticut, turned her home on Old Lyme's main street into a boardinghouse in order to support herself. Griswold's cultured background and natural talents as a conversationalist suited her for the role of gracious hostess, which she played for Ranger and the generations of artists who followed him to her doorstep. Her time-worn home, built in 1817 along the banks of the Lieutenant River, became the epicenter of the Lyme art colony. There, she accommodated the artists' every need, converting barns into studio space, transforming the front hall into an informal gallery for the display and sale of her tenants' artwork, and allowing them to embellish the home's first floor with paintings on the walls and doors. Today her home, open to the public, is a living legacy of creative life on the Connecticut shore.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Charles Herbert Woodbury (1864–1940),

Ogunquit Bath House with Lady and Dog, ca. 1912.

Oil on board, 11-7/8 x 17 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine;

bequest of Elizabeth B. Noyce (1996.38.56).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Gertrude Fiske (1878–1961),

Silver Maple, Ogunquit, ca. 1920,

Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine;

bequest of Elizabeth B. Noyce (1996.38.7).

|

|

|

|

|

|

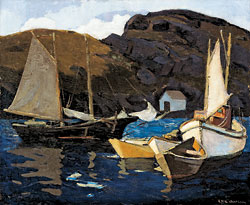

Fig. 8: Walt Kuhn (1877–1949),

Lobster Cove, Ogunquit, 1912.

Oil on canvas, 20-1/8 x 24-1/8 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine; gift of Ellen Williams (2000.43).

|

Ogunquit, a sleepy small town on the rocky coast of Southern Maine, served as the fall line between two artistic cultures in the opening decades of the twentieth century (Fig. 5). By the time of World War I, the picturesque fishing village had become contested terrain in an ideological conflict between artists who traded in the regionalist image of "old" New England and those hewing to a modernist worldview.

Ogunquit, much like Old Lyme, initially attracted a uniform group of like-minded artists—Boston painter Charles Herbert Woodbury (1864–1940) (Fig. 6), a well-known teacher who built a summer home and studio on Perkins Cove in 1897 and established a course of instruction that put Ogunquit on the map as an art colony in the waning years of the nineteenth century. Initially attracted to the narrow cove and surrounding coastal geology, Woodbury and his followers no doubt also appreciated the genteel reputation of their summer venue. "The social atmosphere of Ogunquit is uniformly high-class," noted a popular travel guide in 1911."2 Local residents were bemused, even astonished at times, by the artists in their midst, and stories of their interaction soon became the stuff of legend. One farmer is reported to have said of Woodbury, "I don't know how he could have got 150 dollars for a picture of my cow. I didn't give but 35 for her in the first place, and it don't look like her anyway."3

The rustications of well-to-do Bostonians such as Woodbury and students like Gertrude Fiske (1878–1961) (Fig. 7) were interrupted by the arrival of Hamilton Easter Field (1873–1922), a charismatic New York modernist. Field established his own school in 1911, calling it the Summer School of Graphic Arts and describing the endeavor as "an art school devoted to individual expression."4 In the course of his brief life, Field, who served as an important catalyst for modern art in the United States, founded schools in Ogunquit and Brooklyn and opened the Ardsley Studios, a gallery run out of his Brooklyn home that provided an important venue for modernists including John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Walt Kuhn (Fig. 8), and Marguerite and William Zorach. His most important role, however, was as a spiritual leader in Maine to an emerging group of avant-garde painters and sculptors. He exhorted his students to "open your eyes wide, get the local tang. There's as much of it right here in Maine as there is in Monet's Normandy. But to get it you must live in touch with the native Ogunquit life, just as Monet wears the sabots and peasant dress of Giverny."5 Field also fueled the burgeoning interest in American folk art, collecting furniture, decoys, and weathervanes and using these suggestive objects to decorate the fishing shacks his students used as studios. In this way Field conjoined modern art and maritime culture—a pattern of influence seen on Monhegan as well.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 9: Charles Ebert (1873–1959),

Monhegan Headlands, 1909.

Oil on canvas, 30 x 42 inches.

Florence Griswold Museum;

gift of Miss Elisabeth Ebert (1977.18.1).

|

Settled in the seventeenth century as one of the first fishing communities in colonial America, Monhegan Island evolved into an art colony some two hundred years later. These two seemingly unrelated occupations—fishing and painting—have been intertwined there ever since. As early as 1875, Sarah Albee, a fisherman's wife, provided rooms and meals to tourists. Later she also purchased part of the island's most imposing Federal-style house, known as "the Influence" to house her guests who later included the Cos Cob-based Charles Ebert (1873–1959) (Fig. 9). In the early 1890s, the island's first hotel, the Monhegan House, was constructed next to the schoolhouse, and among the growing tourist trade were a number of artists. In 1903, Samuel Peter Rolt Triscott (1846–1925) was the first artist to settle there year-round. Known for his evocative watercolors of the island's daunting scenery as well as its picturesque houses, Triscott also worked as a photographer and frequently hand colored his prints. From the beginning, the role of photography has been especially strong and is one of the distinctive features of artistic practice on the island.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10: Eric Hudson (1864–1932),

Manana, undated.

Oil on canvas, 28-1/8 x 34-1/16 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine;

gift of Mrs. Eric Hudson (1934.5).

|

By 1900, seven of the thirty-three houses and cottages on Monhegan, belonged to summer people, one of whom was Eric Hudson (1864–1932) who first sailed into Monhegan harbor in 1897, on his way from Bar Harbor to Boston (Fig. 10). Attracted by the rugged landscape, Hudson returned the following year and purchased land that had been part of the old Trefethren Flake Yard, property that belonged to one of the island's old fishing families. The artist immediately began producing his signature sailboat scenes, first with an impressionist palette and later in a darker, more romantic style. Hudson also produced marine photographs, recording boats and harbor scenes from Venice to Monhegan. Some of the posed photographs served as studies for Hudson's paintings, but he took others to capture the hard work entailed in fishing under sail and by hand. His images of local fishermen provide some of the most detailed documentation available of island life at the turn of the century.6

|

|

|

|

Fig. 11: Robert Henri (1865–1929),

Barnacles on Rocks, 1903.

Oil on panel, 8 x 10 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine;

bequest of Elizabeth B. Noyce (1996.38.21).

|

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, Robert Henri (1865–1929) was the most influential artist working on Monhegan (Fig. 11). A teacher at the New York School of Art and a member of the Ashcan School, Henri encouraged his students and more established New York artists to visit the island in the summer months as an antidote to the rigors of urban life. Drawn by its elemental, natural qualities, Henri admired the simple but hard life of the fishermen, the rugged landscape, and the power of the sea. In an effort to capture the changing light and atmosphere on the rocky shores of the island, Henri taught his students to follow his practice of making quick outdoor sketches on small panels. He also produced vigorous, almost abstract sketches of the rocks and trees in the island's woods. Eschewing the high-keyed pastel palette of the impressionists, Henri worked up his scenes in more somber, tonal ranges.

|

|

|

|

| Call of the Coast: Art Colonies of New England chronicles the development of impressionist Connecticut and modernist Maine through their art colonies. It features seventy-four works drawn from the collections of the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine, and the Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut. On view at Portland Museum of Art: June 25 through October 12, 2009; Florence Griswold Museum: October 24 through January 31, 2010. A catalogue of the exhibition is available. For information call 207.775.6148 or visit www.portlandmuseum.org. |

|

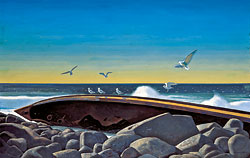

Among Henri's students, Rockwell Kent (1882–1971) established the deepest relationship with the island. He arrived in 1905, bought land on Horn's Hill, and supported himself as a carpenter, eventually building a modest home and studio, as well as a more substantial summer cottage for his mother at Lobster Cove. After his marriage in 1908, Kent managed to paint on the island only in the summer months. But in an effort to ensure a reason for his return, Kent and fellow Henri student Julius Golz established the short-lived Monhegan Summer School of Art in 1910. Following the discovery that year of his extramarital affair with an island woman, Kent abandoned Monhegan, not to return until 1947.7 In his second sojourn on Monhegan, Kent created works now recognized as icons of American painting and the apogee of art-making on the coast of New England (Fig. 12).

The art colonies of New England played a key role in the creation of the region's identity in the early twentieth century. The art colonies in Old Lyme, Cos Cob, Ogunquit, and Monhegan were inspiration for nationally recognized artists including Edward Hopper, Childe Hassam, Robert Henri, and George Bellows, among others.

|

|

|

Thomas Denenberg is the chief curator and the William E. and Helen E. Thon Curator of American Art, and Susan Danly is curator of Graphics, Photography, and Contemporary Art; both from the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. Amy Kurtz Lansing is curator at the Florence Griswold Museum, Old Lyme, Connecticut.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12: Rockwell Kent (1882–1971),

Wreck of the D. T. Sheridan, ca. 1949.

Oil on canvas, 27-3/8 x 43-7/8 inches.

Portland Museum of Art, Maine;

bequest of Elizabeth B. Noyce (1996.38.25).

|

1. Henry Ward Ranger, as quoted in the New Haven Morning Journal and Courier (July 5, 1907).

2. L. S. Woodruff, Souvenir of Ogunquit Maine (Boston, 1911). With thanks to Earle Shettleworth for sharing this booklet.

3. Unidentified farmer quoted in Lewiston Journal (August 7, 1937), in Earth, Sea and Sky: Charles H. Woodbury, Artist and Teacher, 1864–1940, eds. Joan Loria and Warren A. Seamans (Cambridge, MA: MIT Museum, 1988), 34.

4. Hamilton Easter Field, The Technique of Oil Painting and Other Essays (New York: Ardsley House, 1913), 84.

5. Field, Technique of Oil Painting, 58.

6. For a discussion of Hudson's photographs and paintings, see Earle G. Shettleworth Jr. and W. H. Bunting, An Eye for the Coast: The Maritime and Monhegan Island Photographs of Eric Hudson (Gardiner, ME: Tilbury House, 1998).

7. Kent managed to spend the summer of 1917 on the island but accomplished little in the way of art; see Jake M. Wien, "The Return of Rockwell Kent to Monhegan Island, 1917," in Rockwell Kent on Monhegan, 16–19. For a more detailed account of Kent's Monhegan years, see the exhibition catalogue Rockwell Kent on Monhegan (Monhegan Island, ME: Monhegan Museum, 1998).

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format    Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|

|