|

| Home | Articles | What Were They Thinking? Silk Embroideries Give us a Clue |

|

|

|

by Carol Huber

|

|

|

|

The Death of Sylvia's Stag, Maria E. Hoffman, worked at Mrs. Saunders and Miss Beach's Academy in Dorchester, Mass., ca.1820. Silk and paint on silk, with frame, 21 7/8 x 24 3/8 inches.

|

|

|

Silk embroidered pictures made by schoolgirls were the height of fashion in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, often holding a place of prominence in the 'best' parlors where visitors could admire the skill of the maker. Early in the twentieth century these pictures were being purchased by pioneer collectors such as Edgar and Bernice Garbisch, Henry du Pont, Henry Ford, and others, who considered them important because of their association with home and childhood.

|

|

|

|

|

Maternal Affection, Joanna Hoyt of Weare, N. H., in 1805, probably worked at a Boston school. Silk and paint on silk, with frame, 24-1/4 x 26-3/4 inches.

|

|

|

|

Only in the last quarter of the twentieth century, after the publication of several scholarly works including Betty Ring's enormously important two volume Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650–1850 (1993), did collectors begin to learn about the elite academies where middle- and upper-class girls studied and worked these pieces. It was not uncommon for girls to travel great distances to attend one of these schools for a year or more, nor did they necessarily remain at one school, but often enrolled in several.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, anonymous, Massachusetts, ca. 1810. Silk and paint on silk, 15-1/8 x 17 inches.

|

|

|

At the turn of the nineteenth century, these young women were taught an extensive academic curriculum similar to those being taught to young men. As advertised in 1819, the Mrs. Saunders and Miss Beach Academy in Dorchester, Massachusetts, instructed young ladies in 'reading, writing, arithmetic, ancient and modern geography, astronomy, use of globes, use of maps, history, rhetoric, botany, composition, English and French languages.' Students also learned applied arts, including 'drawing, painting in oils, crayons and watercolors, painting on velvet, ornamental paper work, drawing, coloring maps, plain sewing, tambour work, and needlework.' The academy library contained over fifteen hundred volumes including the best classic authors in both French and English. Music and dancing were offered at an additional cost as were all supplies for needlework. Although this curriculum was particularly ambitious, there were many schools and academies throughout the eastern states teaching similar disciplines. All such 'accomplishments' were intended to prepare female students for attracting an appropriate husband and taking their place in society. Boston instructor Susanna Rowson's theory of education for young women was to learn to practice what they needed to know later in life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

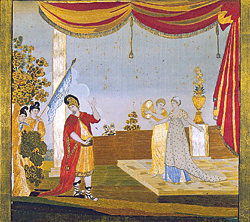

The Royal Palace in Alexandria, Antony, Cleopatra, Eros, Charmain, Iros, etc., anonymous, worked at Susanna Rowson's Academy, Boston, Mass., ca. 1805. The faces and background were painted by John Johnston (1753–1818). Silk and paint on silk, with frame, 26-5/8 x 32-1/4 inches.

|

|

|

|

Maria E. Hoffman stitched The Death of Sylvia's Stag at the Saunders and Beach Academy in the early 1800s. The scene from Virgil's Aeneid shows Sylvia, daughter of Tyrrheus, bending over her dying pet stag who has been shot by Iulus, son of Aeneas. This incident leads to the outbreak of war between Aeneas and the Rutulians. Surely Maria did not spend numerous hours stitching this complicated picture without knowing the story of the Trojans. It must have been a favorite story at this and other schools as several pictures with this scene survive.

|

|

|

|

|

Jephtha, worked at Lydia Royse's school, Hartford, Conn., ca. 1805. Silk, velvet and fabric applique, paint on silk, with frame, 26-1/2 x 28-1/2 inches. Mrs. Royse was known for her artistic skill and painted the faces and backgrounds of embroideries for her students. An elaborate frame with shell corners and an unusual gold 'glomis' surround this picture.

|

|

|

Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, was a popular subject for young ladies in New England. A second-century BC Roman matron, Cornelia was the widowed mother of three children, with a reputation for goodness and wisdom. When a rich woman brought a box of jewels to show Cornelia and then asked to see hers, Cornelia pointed to her children and said, 'These are my jewels.' Her young boys grew up to be exemplary statesmen, though both were murdered as a result of their good doings. Several embroidered pictures from different schools were based on an engraving entitled Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi by Francesco Bartolozzi (1729–1815), after a 1785 painting by Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) published in London in 1788. The needleworks bear such titles as These Are My Jewels, Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, and Maternal Affection. Joanna Hoyt, of Weare, New Hampshire, labeled her rendition the latter in September 1805. She most likely attended school in Boston where similar pictures were produced.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jephtha Repenteth His Rash Vow, Beulah Child, East Haddam, Conn., worked at the Misses Pattens' school, Hartford, Conn., ca. 1810. Silk, metallic thread, gold foil, and paint on silk, with frame, 25-3/4 x 23-1/8 inches. Heavy metallic fringe decorates the draperies and the faces are very primitive, indicating they were most likely painted by the stitcher.

|

|

|

The typical composition of this scene depicts Cornelia and the other figures in Roman garb in a classical setting of large columns, tiled floors, and a hilly Italian landscape. But one unusual needlework shows Cornelia entertaining her rich guest in a fashionable circa-1810 parlor; both are attired in the current Empire fashion, as is the youngest child. Cornelia is pointing to her sons, who are set apart in their Roman garb. This updated interpretation may have been designed by either the schoolmistress or the student.

The Royal Palace in Alexandria, Antony, Cleopatra, Eros, Charmian, Iros, etc. was worked by an unknown young lady most likely at the academy of Susanna Rowson in Boston, circa 1810. It is the exact size and likeness of a 1795 engraving by G. N. and J. G. Facius, after a painting by Henry Tresham, published on December 1 of the same year by John and Josiah Boydell in London. The image was obviously traced onto the silk directly from the print. Based on Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, Act III, Scene IX, the dialogue reads:

Eros: the Queen, my Lord, the Queen

Iras: Go to him, madam, speak to him;

He is unqualitied with very shame.

Cleopatra: Well then—Sustain me:––O

Eros: Most noble sir, arise the

Queen approaches, Her head's declin'd

and death will seize her; but Your comfort

makes the rescue,

Antony: I have offended reputation;

A most unnoble swerving.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Hermit, anonymous, Mrs. Lydia Royse's school, Hartford, Conn., ca, 1810. The painted features are attributed to Mrs. Royse. Silk and watercolor on silk, with frame, 25-1/2 x 29 inches.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rosina, anonymous, Samuel Folwell design, Philadelphia, ca. 1810. Silk and paint on silk, with frame, 23 x 27 inches.

|

|

|

|

|

Shakespeare was widely read at girls' academies, so it is not surprising that this subject was selected for an embroidery project. The quality of the stitching suggests that this young lady was adept with the needle. The fact that the faces were painted by the Boston artist John Johnston (1753-1818) suggests that she came from a wealthy family. It was not unusual for the faces and backgrounds of silk embroidered pictures to be painted by a professional artist for a fee. More often, painted areas were executed by the teacher or the student herself.

Biblical subjects were also the basis for needlework composition: Moses in the bulrushes, Mary and Joseph with the baby Jesus, the sacrifice of Isaac, Ruth, and Naomi, and Ruth and Boaz to name a few. In New England, the Old Testament story of Jephtha (Jephthah) was very popular, most likely because the tragic ending appealed to the imaginations of the young ladies. Jephtha was a judge in Israel who led the war against the Ammonites. Before going into battle he promised God that if successful he would offer as a sacrifice the first person to greet him on his return home. Jephtha returned home victorious and was met by his only child. His daughter dutifully surrendered her life so that the heartbroken Jephtha could keep his promise.

This powerful story captured the minds of two girls attending two Hartford, Connecticut, schools. An anonymous stitcher worked her version at Lydia Royse's school, circa 1815, and Beulah Child from East Haddam created her version at the Misses Pattens'school at about the same time. Techniques and materials differed. Lydia Royce most likely painted the faces and background of the piece worked by the student at her school. Beulah's piece exhibits more primitive painting, which she probably did herself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Castle of Indolence, Mary Wyatt Carpenter, N. J., 1799, probably stitched in Philadelphia. Silk and watercolor on silk, 23 x 27 inches.

|

|

|

Rosina, the light opera composed by William Shield (1748–1829) and first performed December 31, 1782, at Covent Garden, London, was the inspiration for several beautiful embroideries worked at Samuel Folwell's school in Philadelphia. The pattern for the anonymous embroidery shown here was designed by Folwell, whose wife Elizabeth taught needlework at the school. The selected scene illustrates Mr. Belville asleep under a tree, devastated by the effects Rosina has had on him. Upon finding the sleeping Belville, Rosina uses one of her ribbons to tie the branches of a tree together to shade him from the sun. The romantic comedy, filled with love, rejection, good, and evil–with a happy romantic ending–was an enticing subject for young ladies eager to find a suitor.

Poetry and recitation were important elements in female education. An embroidery, probably worked at Lydia Royse's academy in Hartford, Connecticut, has its roots in the epic poem The Hermit by the Anglo-Irish clergyman Thomas Parnell (1679–1717). The poem relates how a hermit undergoes a series of encounters with vice and virtue in an effort to understand both himself and the world. The scene in this embroidery is from an engraving by Benjamin Tanner (1775–1848) based on the poem. Several embroideries exist showing this particular scene, long thought to be a biblical scene. It was not until an embroidery was found with an inscription on the glass that read, 'But Scarce his speech began, when the strange partner seem'd no longer man,' that the subject was connected to the poem with the engraving as the source.

|

|

|

|

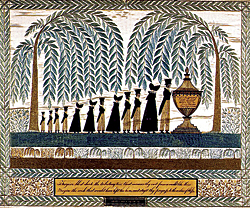

Memorial to Enoch Long, Mary Banforth, Jaffrey or Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire,1822. Silk, graphite, and paper on silk, with frame, 20 x 23-1/4 inches.

|

|

|

To be wary of, and perhaps warn others about the pitfalls of an affluent lifestyle, Mary Carpenter, based her embroidery on the poem The Castle of Indolence, by James Thomson (1700–1748). This poem includes the verse: 'The Castle hight [sic] of Indolence, and its false luxury; Where for a little time, alas! We lived right jollily.' A poem expounding the virtues of labor over the self-serving lifestyle of the rich, the scene shows the contrast between cottage and castle. The silkwork includes an inscription on the back: 'Mary Wyatt Carpenter married James Hunt, April 4, 1800 in the 18th year of her age. Made Castle of Indolence in the 17th year of her age. Took lessons from a nun.' This important label was the key in identifying the subject of the embroidery, as the print source is unknown. Mary was born June 3, 1783, the daughter of William and Elizabeth Wyatt Carpenter, in Mannington Township, Salem County, New Jersey. She most likely attended school in Philadelphia.

A more personal style of embroidery took the form of memorials, which were very much in vogue, particularly after the death of Washington in 1799. So popular was this genre of needlework that sometimes memorials were left blank because there was no one to dedicate it to or because the stitcher intended to add an inscription at a later date.

One very touching and exceptionally graphic memorial was created by Mary B. Banforth in either Jaffrey or Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire, and was most likely designed with the help of her teacher. The scene depicts a family in silhouette mourning the death of their youngest son.[1] The monument is inscribed, 'Sacred to the memory of/ Enoch H. Long/ who departed this life/ June 28, 1822/ Aged 6 years, 6 m.' An inscription on paper written by Mary reads, 'FORGIVE, blest shade, the tributary tear, that mourns thy exit from a world like this:/ Forgive the wish that would have kept thee/ here, and stay'd thy progress to the realms of bliss.' Mary was engaged to the oldest son; family history states she made this as a gift for him. The piece is beautifully executed with exquisite costume details; ruffled collars, bonnets and top hats, little shoes below hemlines, and a sense of grief expressed by handkerchiefs covering faces.

The surviving silk work pictures that resulted from an academy education give us an insight into the guidance teachers provided young women. These dedicated instructors took seriously the duty of educating in the academic sense, but also morally, and always with an eye for beauty.

[1] Research identifies the family (right to left) as the father Issac Long, mother Susanna Kimball Long, and children–fiancee John b.1794, Rufus b.1797, Nancy b.1799, David b.1801, Sara b.1803, Sally b.1805, Edward b.1807, Issac b.1809, Charles b.1811, and William b.1813.

|

|

|

|

Carol Huber, with her husband, Stephen, specializes in American girlhood embroideries and are owners of Stephen & Carol Huber, Old Saybrook, Connecticut. Carol has written and lectured extensively on the subject of American school girl needlework, and appeared on the television programs Martha Stewart and Find!.

All photogaphy courtesy of Stephen & Carol Huber.

|

|

|