|

| Home | Articles | Of, By and for the People: The Art of the Presidential Campaign |

|

|

by Jeff Pressman

|

|

|

|

Quadruple jug, 'Jackson shooting Adams,' American, ca. 1824. Incised and cobalt decorated salt-glazed stoneware, H. 9, Diam. 9 in. Courtesy of Rex Stark.

|

In 1836, after serving two terms as president, Andrew Jackson expressed two regrets: 'I didn't shoot Henry Clay, and I didn't hang John C. Calhoun.' These tough sentiments recall events that shaped American politics, and which were artfully recorded by folk artists of the day, active participants in political commentary.

Prior to 1828, true organized political parties did not exist although there were basically two factions: the Federalists who supported strong central government, and the Democratic-Republicans, who were states' rights supporters. In the presidential election of 1824, Andrew Jackson won a plurality of the electoral and popular vote, but failed to win a majority, throwing the election to the House of Representatives to decide. Henry Clay had polled fourth in electoral votes and was therefore not eligible for election. He met privately with John Quincy Adams twice before the House voted and threw his support behind Adams, giving Adams the majority of votes. Shortly afterwards, Adams appointed Clay as his secretary of state, enraging Jackson and his supporters, who claimed a 'corrupt bargain' had been made. Though there is no documentation to support the allegation of a quid pro quo, the stoneware jug showing Jackson shooting Adams summarizes the hard feelings felt by Jackson's supporters after the election.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sgraffito plate, Samuel Troxel, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, 1828. Glazed red earthenware. Inscribed 'Liberty for Gackson [sic].' Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased with the Baugh-Barber Fund, 1960. 1960-120-1.

|

As one might imagine, the bitter feelings over this election signaled the end of the so-called Era of Good Feelings and a one party system. The 1828 presidential campaign began almost as soon as the Tennessee legislature nominated Andrew Jackson in 1825. A new political party, the Democratic–Republicans formed around Jackson, while Adams supporters remained less organized, finally coalescing as the National Republicans. Passions ran high as Jackson's supporters portrayed his opponent, Adams, as elitist and accused him of using government funds to purchase gambling equipment for the White House; in reality, he'd purchased a pool table with his own money. Adams' supporters leveled their own accusations, calling Jackson's mother a prostitute and his wife, Rachel, a bigamist. The Jacksons believed her divorce had been finalized when they married; after they learned otherwise, they married again, though Jackson felt the slurs directed toward his wife were responsible for her death shortly after the election. In 1828, Jackson's political allies pushed through high tariff rates protecting raw materials, gaining him votes in Western states and a decisive majority in both the popular and electoral vote, including Pennsylvania, where potter Samuel Troxel made this pro-Jackson sgraffito plate, extraordinary in its abundant decoration, political slogan,spreadwing eagle,

and signature of the maker.

|

|

|

Steamboat Veto box. Artist unidentified, possibly New York State, ca. 1832. Paint, gold leaf, and bronze powder stenciling on wood. 5-1/2 x 13 x 7-5/8 inches. Courtesy of American Folk Art Museum, New York; gift of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration, 76.5.2. Photo by John Parnell.

|

Although the Tariff of 1828 helped Jackson secure the election, it came with a terrible price – sectionalism. Known as the Tariff of Abominations, Jackson's vice-president, John C. Calhoun, led a campaign to nullify it in his home state of South Carolina, where the legislature passed a bill making it illegal to collect the tariff. When South Carolina threatened to secede over the tariff, Jackson, who viewed South Carolina's action as unconstitutional and Calhoun's actions as treasonous, sought and obtained approval to use the armed services, if necessary, to enforce it. The compromise Tariff of 1833, which gradually reduced the rates to 1816 levels, was introduced by Henry Clay and diffused the crisis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

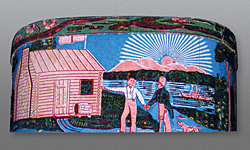

William Henry Harrison wallpaper hatbox, American, ca. 1840. Paper board and block-printed paper, H. 12, W. 16, L. 12 in. Courtesy of a private collection; photography by David Wheatcroft.

|

|

Jackson's long-standing mistrust of banks and their potential of concentrating too much control over the government were focal points of the 1832 election. That year, Henry Clay, Jackson's likely opponent, ushered a premature bill through Congress reauthorizing the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, not due to expire until 1836. Clay felt support of the bank was an issue he could campaign on and believed it might help him in Pennsylvania where the bank was based. Jackson, concerned about the power of Nicholas Biddle, president of the Second Bank of the United States, and of the bank itself, vetoed the re-charter bill. The box (above) shows the steamship Veto, likely referring to Jackson's actions, given Clay's characterization of the bank in more benign terms as, 'a mere vehicle; just as much so as the steamboat is...and not the grower of that produce.'1

|

|

|

|

|

|

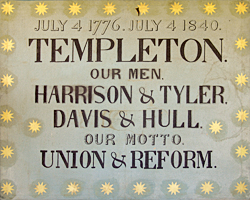

Harrison–Tyler parade banner, Templeton, Mass, 1840. Oil on canvas, 45 x 35-1/2 x 2 inches. Courtesy of Narragansett Historical Society. Photo-graphy by Brian Tanguay. The reverse reads: 'July 4 1776. July 4 1840. Templeton. Our Men. Harrison & Tyler. Davis & Hull. Our Motto. Union & Reform.'

|

|

|

Reelected by an overwhelming majority, Jackson took this as a mandate to continue his attack on the Second Bank of the United States. He ordered funds withdrawn from it and deposited into, what became known as 'pet banks' that he deemed as friendly. His secretary of the treasury, William Duane, refused, arguing the transfer was illegal. Jackson fired him and replaced him with Attorney General Roger Taney, who executed Jackson's orders. Jackson followed up with the Specie Circular, an executive order that required payment for land sold by the government in gold or silver (specie). This led to a credit shortage that saddled Martin Van Buren with the financial panic of 1837 and the ensuing depression. Jackson's heavy-handed actions led his opponents to label him 'King Andrew' and gave rise to a new opposition party, the Whigs, who took their name from the colonists who had opposed King George.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Reverse of Harrison-Tyler parade banner above. |

|

In 1836, the newly formed Whig party ran three candidates in different regions of the country. Their hope was to prevent Jackson's nominee, Martin Van Buren, from winning an outright majority. Had they succeeded, the election would have been decided in the House of Representatives, where the Whig candidates held a majority and could select a Whig president. This strategy failed, but set the stage for the election of 1840. This was the first modern election in U.S. history, where one of the candidates (Whig William Henry Harrison) gave speeches on his own behalf; when campaign paraphernalia (metal tokens, jewelry, china, ribbons, and bandanas) other than political newspapers were widely distributed; and mass rallies and parades were convened.

|

|

|

Clay parade banner, American, 1844. Paint on cloth. Courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection. Photography by Jim Frank.

|

|

|

The 1840 election was also the first time that a party, the Whigs, held a convention to select a candidate. Henry Clay and Winfield Scott lost to Harrison. After the latter won the nomination, a disgruntled Clay supporter was heard to say, 'Give him a barrel of hard cider and a pension of two thousand a year and, my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in a log cabin by the side of a &'sea coal' fire and study moral philosophy.' Newspapers published the derogatory quote, but the Whigs turned it to their advantage, portraying Harrison as a common man born in a log cabin and a friend of the people. In fact, the 'log cabin' candidate's father was a wealthy landowner, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, and a governor of Virginia. Harrison had earlier gained national fame for leading U.S. forces against American Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, earning him the nickname 'Tippecanoe,' which gave rise to one of the most popular campaign slogans of all time, 'Tippecanoe and Tyler Too,' – a reference to John Tyler, Harrison's vice-presidential choice. A wallpaper hatbox shows Harrison welcoming a wounded veteran to his log cabin on the banks of the Ohio River, identified by the steamship Ohio. A barrel of hard cider sits in front of the cabin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fremont-Dayton parade banner, New Hampshire, 1856. Paint on cloth, 46 x 37 inches. Courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

|

|

|

In their campaign materials, the Whigs portrayed Van Buren, known as the Red Fox of Kinderhook––a reference to his birthplace in New York––as an elitist, although he, in fact, was the self-made man. A Whig banner from 1840 shows Van Buren trapped in the 'Sub Treasury Fox Trap,' with Amos Kendall, editor of the Washington Globe, the organ for the Jackson Administration, struggling to rescue him from the trap with his pro-Van Buren newspaper. Van Buren's proposed solution to the financial panic of 1837 and ensuing depression was the sub treasury, a plan to deposit gold and silver in vaults in cities throughout the United States, in lieu of a central bank, where it could be accessed when needed (Van Buren's gold buttons signify his support of specie, or hard currency). Harrison won easily, but developed pneumonia and died thirty-one days after taking office. Tyler, his vice-president, was not supportive of Whig policies and so Harrison's election turned out to be a hollow victory.

Annexation of Texas, a state that endorsed the ownership of slaves, was a key issue in the 1844 election. Democratic Party candidate James K. Polk favored annexation as well as further geographic expansion west. His Whig opponent, Henry Clay, initially opposed annexation, and later alienated Northern Whigs by equivocating. Whig policy also favored protective tariffs to pay for a national system of roads and canals, and by 1842, had restored tariff levels to those before 1832. The Whig parade banner depicts Clay (on the left) as the hero of the protective tariff. Below the figures of Clay and Polk, the verse reads: 'Thus Polk the scoundrels tries / Our Tariff to[o] low to Lay / While to its rescue flies / Our Gallant Henry Clay.' Polk (on the right) is attempting to shoot Henry Clay. The ball and chain attached to his leg is labeled 'Texas.' Depicted as a liability here, Clay's position on Texas actually cost him the election in his third attempt at the presidency.

Despite never succeeding to the presidency, Clay remained a vital politician in the 1840s and 1850s. When the Northern and Southern states were wrangling over the admission or exclusion of slavery in the territories recently acquired from Mexico in the U.S.-Mexican War, Clay helped work out what historians have called the Compromise of 1850 that led to California's admission as a free state and further strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Act, which satisfied pro-slavery advocates.

|

|

|

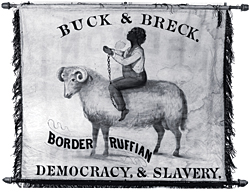

When the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 divided the territory of Nebraska into the Nebraska territory and the Kansas territory, allowing each to decide on whether slavery would be legal, sectional tensions raged. Democratic Party candidate James Buchanan, who ran in 1856, favored popular sovereignty, allowing each territory to decide whether to be a slave or a free territory. His opponent, John C. Fremont, whose opposition to slavery won him the nomination as the newly formed Republican Party candidate, ran with the slogan, 'Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Men, Fremont.' The Republicans of New Hampshire carried a banner in parades that read 'Fremont and Dayton' on the front and 'Buck and Breck' short for Buchanan and Breckinridge, on the reverse. The image of a slave in chains linked the Democratic Party to a pro-slavery platform.

|

|

|

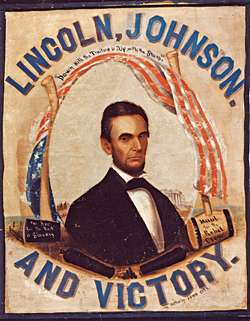

Lincoln-Johnson parade banner, Isaac Wetherby, Iowa City, 1864. Paint on Cloth. Courtesy of Putnam Museum of History and Natural Science, Davenport, Iowa.

|

The Kansas-Nebraska Act essentially nullified the Missouri Compromise passed in 1820 that prevented the extension of slavery north of the 36.30 parallel. It had a profound affect on Abraham Lincoln, who had decided in 1848 not to run for Congress after serving six years in the House of Representatives. In response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Lincoln reentered politics, campaigning in favor of the limitation of slavery and running as the newly formed Republican Party candidate for the Senate against Democrat Stephen Douglas in 1858. Douglas was victorious and went to the United States Senate, but the election gave Lincoln national recognition and led to his nomination as Republican Party candidate for president in 1860.

Sectionalism reached its peak in the election of 1860. The Democratic Party split into Northern and Southern parties, each fielding their own candidates for president. A fourth party, the Constitutional Union Party, formed in 1860 by former Whigs whose party had dissolved in 1856, had only one object, to preserve the Union. Lincoln won with a majority of the electoral votes, but only a plurality of the popular vote. South Carolina immediately seceded and the Civil War began just as Lincoln assumed the presidency. By 1864, Lincoln himself was doubtful he would be reelected. New England itinerant artist Isaac Wetherby, a devoted abolitionist, did not share Lincoln’s doubt. After moving his family to Iowa City in 1854, Wetherby, who continued to make a living as a painter and photographer, recorded in his daybook the painting of campaign banners for Lincoln. In it, he wrote, 'I charge nothing for my painting, [I] went in for the Glory.' A newspaper article pasted in his daybook states, 'We saw a very fine life size portrait of our next president Mr. Lincoln, painted by Mr. I Wetherby, of Iowa City, and said to be an excellent likeness. An axe, maul, wedges, and the stars and stripes surround the portrait.'2

Folk artists continued to produce parade banners in the latter half of the nineteenth century, although printed banners increasingly took over and the invention of the celluloid campaign button in 1896 dramatically altered memorabilia made for campaigns.

|

|

|

Of, By and For the People: The Art of Presidential Elections, is on view September 20, 2008 through December 31, 2008 at the Fenimore Art Museum, New York State Historical Association, Cooperstown, New York. For information call 607.547.1400 or visit www.fenimoreartmuseum.org.

1. Stacy Hollander and Brooke Davis Anderson, American Anthem Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York, Harry N. Abrams, 2001), 87, 325. The author would like to thank Stacy Hollander for calling this box to his attention.

2. Michael R. Payne and Suzanne R. Payne, 'The Business of an American Folk Portrait Painter: Isaac Augustus Wetherby.' Folk Art 21, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 59–67. The author wishes to thank the Paynes for their information about Isaac Wetherby.

|

|

|

Jeff Pressman is a collector, president of the American Folk Art Society, and guest curator of Of, By and For the People: The Art of Presidential Elections.

|

|

|