|

| Home | Articles | The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950 |

|

|

|

by Emily Ballew Neff

|

While the main storyline in American art has always emphasized the importance of urbanism -- especially machine-age technology -- a new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, argues that the vast, rugged land of the American West has also left an indelible mark on modernism. The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950, presents 110 paintings, works on paper, and vintage photographs by Frederic Remington, John Henry Twachtman, Edward Sheriff Curtis, Georgia O'Keeffe, Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Dorothea Lange, Maynard Dixon, Jackson Pollock, Ansel Adams, and others, in its exploration of the connections between the West, modernism, and ideas about national meaning. For these artists, the West provided a "new" environment in which to construct a "new" American art. In six roughly chronological sections the exhibition traces how early artists, as part of survey expeditions, made the landscapes of the American West accessible and legible to the American public; how subsequent artists found ways to interpret the West through their own artistic lenses; how the concept of a monolithic West gave way to an appreciation of its regional contours, most productively in the Southwest; and how, following the disasters wrought by nature and humankind during the Dust Bowl era, certain artists articulated these landscapes in new and groundbreaking ways.

|

|

Text continued at bottom of article.

|

|

|

Ansel Adams (1902-1984)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ansel Adams (American, 1902-1984), Surf Sequence (one of five), 1940. Gelatin silver photograph, printed 1941. 8 x 9-5/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Anonymous gift. ©The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

|

Although best known for his work in California's Yosemite National Park, Ansel Adams actually lived on the California coast. In Surf Sequence, he captures the surge and retreat of waves on the beach over a period of time. His close observations track the subtle patterns found in nature as well as the ephemeral pleasures to be found in its rhythms. The sequence of images emphasizes the point that no one photograph can be an authentic marker of place. Some viewers regarded this work as abstract, but Adams preferred the term "extract."

|

|

|

Frederic Remington (1861-1909)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frederic Remington (American, 1861-1909), The Scout: Friends or Foes? (The Scout: Friends or Enemies?), 1902-1905. Oil on canvas, 27 x 40 inches. Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA.

|

The stark landscape plays a crucial role in this early-twentieth-century Frederic Remington painting that evokes the then-popular idea of the vanishing West. A Blackfoot Indian scout, alone and noble looking, as if he were the last of his race, peers down from a precipice to an encampment below. The abstract quality of the terrain describes an empty space waiting to be filled, a vast place where heroic dramas could be enacted, or from where indigenous cultures might disappear into thin air.

|

|

|

Stuart Davis (1892-1964)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stuart Davis (American, 1892-1964), New Mexican Landscape, 1923. Oil on canvas, 32 x 40-1/4 inches. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas. ©The Estate of Stuart Davis / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

|

A trip to New Mexico forever changed the artistic approach of Pennsylvania native Stuart Davis. Perhaps influenced by the sculptural landforms, vivid angles, and saturated colors of the region, Davis turned away from Synthetic Cubism and increasingly used planar abstraction in his subsequent works, as seen here. Separating himself from the dominance of European styles, Davis followed his conviction that there could be an authentic American style and subject matter informed by the land and its people. For him, the landscapes of the Southwest were modern.

|

|

|

Thomas Moran (1837-1926)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Moran (American, born England, 1837-1926), Mountain of the Holy Cross, 1875. Oil on canvas, 82-1/8 x 64-1/4 inches. Courtesy of the Autry National Center, Museum of the American West Collection, Los Angeles. Donated by Mr. and Mrs. Gene Autry.

|

Artists accompanied early survey expeditions west, but their depictions of the landscape were not always faithful to topography. This picture of a mountain in Colorado is actually a composite view of the waterfall, the mountain bearing an image of a cross, and the path leading toward it. Critics of the time applauded Moran's performance, but a few complained, faulting him for failing to convey a sense of space in the wide open terrain of Colorado. Moran, however, was well aware of the optical sensations in the West that challenged conventional notions of space. By compressing distance, he could transform the mountain into an emphatic symbol of manifest destiny.

|

|

|

Grant Wood (1891-1942)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Grant Wood (American, 1891-1942), Spring Turning, 1936. Oil on Masonite panel, 18-1/4 x 40-1/4 inches. Reynolda House, Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. ©Estate of Grant Wood / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

|

In the 1930s, while some artists of the Midwest created images of fields and farms ravaged by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, Grant Wood focused on the enduring serenity and structure of agrarian life in his native Iowa. Spring Turning depicts a quaint vision of a farm, revealing nostalgia for a different rhythm of life and a longing for innocence. Affiliated with American Scene painting, a realist style established to counter European modernism, Wood painted subjects that were particular to his region, believing that an "authentic" American art would result. Through a reductive streamlining to basic shapes, a minimal palette, and an evenness of detail, Wood makes agricultural order -- as well as his artistic discipline -- a Midwestern value.

|

|

|

Gottardo Piazzoni (1872-1945)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gottardo Piazzoni (active United States, born Switzerland, 1872-1945), The Sea, 1915. Oil on canvas, 48 x 124 inches. University of California, Berkeley Art Museum, Gift of Helen and Ansley Salz.

|

In the early decades of the twentieth century, various regions within the West began to emerge with their own particular identities -- and artistic styles. In California, the soft contours and romantic views of pictorialism (in photography) and tonalism (in painting), prevailed longer than in other parts of the country, perhaps perpetuated by the idyllic landscape. Here Gottardo Piazzoni reduces the coast of California to minimal blue-gray tones and spare, rectangular shapes, which help convey the serenity of the scene. Like a note on a musical scale, a sail in the distance interrupts the calm stillness of the sea. The scale of this painting, which is ten feet long, suggests the great expanse of the Pacific Ocean, the outermost limit of the West.

|

|

|

Raymond Jonson (1891-1982)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Raymond Jonson (American, 1891-1982), Cliff Dwellings, No. 3, 1927. Oil on canvas, 48 x 38 inches. Jonson Gallery Collection, University Art Museum, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Bequest of Raymond Jonson.

|

For many artists in the Southwest, the strange geology and the indications of ancient cultures provided a rich vocabulary for addressing the issues of "Americanness" and the concept of modernity. Jonson's painting perfectly expresses this dynamic; emblems of ancient cliff dwellings and the pines of the Pajarito Plateau thrust upward like New York skyscrapers, while the eerie background "lights" are reminiscent of a city at night. Jonson seems to indicate an ancient pedigree for the modern skyscraper through references to ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) cave dwellings. By merging machine-age symbols with the Southwest's ancient civilizations, Jonson articulated what it meant to be both modern and American.

|

|

|

Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Hart Benton (American, 1889-1975), Boomtown, 1927-28. Oil on canvas, 45 x 54 inches. Memorial Art Gallery, University of Rochester; Marion Stratton Gould Fund. ©T.H. Benton and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

|

Like the train and the plow, the oil derrick had an effect on the West. In Boomtown it is shown serving as a magnet for those looking for new opportunities. This scene of the town of Borger, in the Texas Panhandle, is one of Thomas Hart Benton's greatest Regionalist works. Benton's rubbery figures -- cowboys, farmers, businessmen, buxom women, toughs, African-Americans, and a menacing figure, at lower right, carrying a knife -- inhabit a remarkable landscape. Using a bird's eye perspective, Benton looks down and across the vast landscape, so that the foreground slips into the viewer's lap and the background stretches endlessly in the distance, punctuated by telephone poles, enclosed oil wells, and derricks. The town merges with the oil field, and black smoke spews like an apocalyptic cloud, but no one seems to notice, except for the voluptuous woman in white, who raises her umbrella, confusing carbon clouds for a brewing thunderstorm. In this expansive scene of the West, Benton seems to take delight in its contradictions, as he finds freedom in Borger's anarchy and shame in the ambivalence that the people in it express toward their surroundings.

|

|

|

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986)

|

|

|

|

|

|

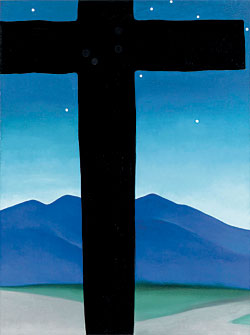

Georgia O'Keeffe (American, 1887-1986), Black Cross with Stars and Blue, 1929. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches. Mr. and Mrs. Peter Coneway. ©The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

|

More than any other artist of her time, Georgia O'Keeffe was the most highly disciplined in the development of her geographical perceptions of the Southwest. One of her greatest series of paintings is of the crosses she found in the landscape around Taos, New Mexico. Here, O'Keeffe accentuates the cross so that it hovers over the mountain rather than under it. In reality, Taos Mountain appears enormous from any vantage point, both protective and overwhelming, yet O'Keeffe makes it somehow manageable, narrowing the sweeping Taos Valley into a shadowy wedge of green. Using crystallized forms and precisionist lines, O'Keeffe suggests how land and life in New Mexico inform each other. And, more fundamentally, that there is something sacred to be learned from the land, especially a place so historically fraught as New Mexico, where to see the land one must view it through the events that have occurred there -- symbolized here through the Penitente cross that appears in the middle of a valley, reframing the landscape.

|

|

|

Jackson Pollock (1912-1956)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956), Night Mist, 1944. Oil on canvas, 39 x 72-1/8 inches. Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL; Purchase, the R.H. Norton Trust, 71.14. ©The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

|

Jackson Pollock was not a landscape painter, but the West, where he was born and reared (in Cody, Wyoming), had a tremendous impact on his art. Drawn to the symbols of ancient cultures and American Indian art, Jackson Pollock generated his own kind of iconography, some snippets of which can be seen here. Symbols of a primordial spirit world -- fragmented images of humans, birds, eyes, and faces -- lurk beneath a web of white paint. Pollock internalized the western landscape and its cultures, expressing them in a new, dynamic way, which led him to become a pioneer of abstract expressionism.

|

|

|

Timothy H. O'Sullivan (1840-1882)

|

|

|

|

|

|

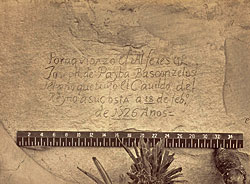

Timothy H. O'Sullivan (American, born Ireland, 1840-1882), Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock, New Mexico, 1873. Albumen silver photograph, 8 x 10 inches. Robert G. Lewis Collection.

|

This image, one of the most famous American photographs of the nineteenth century, documents one of many autographs inscribed over several centuries on a sandstone promontory in New Mexico. The startling precision and clarity of photographer Timothy O'Sullivan's work underscores the purpose of early government surveys: to measure the West at a time when much of America's western lands were just becoming known. However, when O'Sullivan's photographs were rediscovered in the 1930s, their appeal lay in their spare lines, flat, reductive surfaces, and seeming simplicity.

|

|

|

The Modern West, opening in Houston in October 2006, marks the 200th anniversary of the expedition of explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the uncharted land of the American West. The information they gathered on the nearly 8,000 mile round-trip expedition became the basis for the ambitious geological and geographic surveys undertaken between 1867 and 1879. Photographs from these surveys, such as Timothy O'Sullivan's canonical Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest, South Side of Inscription Rock, New Mexico, provided records of the prehistoric ruins, pueblo villages, seventeenth-century Spanish military and clergy, and nineteenth-century Euro-American settlers of the American West.

The year 2006 is also the fiftieth anniversary of the death of abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, credited with the radical innovations in painting that led to New York's internationally central position in the art world in the mid-twentieth century. A Westerner by birth, Pollock's background and his experiences with American Indian cultures colored his artistic enterprise. Paintings such as Night Mist rec"all the rich layering of American Indian compositions that he saw in his childhood. Despite a nearly eighty year gap between the era of survey photography and Pollock's mature career, they share a deep connection with ideas about time, space, history, and the clash of cultures played out in the American West.

|

The Modern West: American Landscapes, 1890-1950 will open to the public at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, on October 29, 2006, and will be on view through January 28, 2007. The show then travels to Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it will be presented from March 4 to June 3, 2007. The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue published by Yale University Press in association with the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

|

|

Dr. Emily Ballew Neff is curator of American painting and sculpture at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. She is the author of Frederic Remington: The Hogg Brothers Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and other works. Dr. Neff would like to acknowledge Heather Brand in the museum's publications department for her assistance in compiling the image captions.

|

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format     Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|

|