|

|

|

|

|

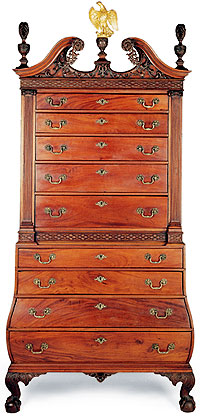

Attributed to John Cogswell (1738–1819) Attributed to John Cogswell (1738–1819)

Carving attributed to the shop of John and Simeon Skillen

Boston, Massachusetts, circa 1780

In three sections: the upper section with removable scrolled pediment with elaborate ruffle, foliate carving, and carved rosette terminals with dependent trailing swags above an applied blind-fretwork frieze; the upper case with five beaded graduated drawers flanked by fluted pilasters surmounted by ionic capitals, all above a waist with blind fretwork of a similar design; the lower case with swelled sides enclosing four conforming, beaded graduated drawers, the molded base below with central C-scroll and ruffle-carved drop pendant on acanthus-carved cabriole legs ending in hairy claw-and-ball feet with hairy talons, each flanked by carved, shaped brackets.

Condition:

When Leigh Keno first encountered this object, the plinths, finials, and carved rosettes from the pediment were missing. The barrel terminals (upon which the original rosettes had been applied) were carved with a pinwheel motif and a similar semicircular fan rested on the central plinth. A small (1” x 1 1/2”) passage of the rococo leaf pattern on the right side of the pediment had also been poorly replaced in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The removable pediment was coated with a thick lacquer, making it appear darker than the rest of the piece. Simple Doric moldings replaced the original capitals of the pilasters, and the blind fretwork at the waist (at the bottom of the upper section) was also missing. The upper and lower cases had been cleaned in the late nineteenth century, but much of the original surface on the moldings, carved feet, and open drop pendant was preserved. The piece retained its third set of brasses, and the drawer front around each central keyhole had been pierced, with wooden roundels inset as escutcheons. (Interestingly, another chest of drawers in the house was updated with the same brasses and escutcheon treatment, probably done at the same time.)

Once secured by Leigh Keno American Antiques, Alan Anderson and his staff restored the chest-on-chest. When the lacquer from the pediment was removed in December 2000, it was discovered that the fretwork on the right side was replaced. This fretwork was re-replaced to more accurately match the front and side panels. The signed Cogswell chest-on-chest at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which retains most of its original ornament, was used as the prototype for reconstructing the missing pediment ornaments on the present example. With the help of Jonathan Fairbanks, Gerald Ward, and Gordon Hanlan of the MFA as well as with Keno, Andersen and carver Rob McCullough took measurements and photographs, making the detailed drawings necessary for the restoration of the missing ornament.

The finials, plinths, and rosette terminals were reproduced based on the group’s analysis. Their examination, as well as others before, determined that the urn-and-ball finial supporting the carved eagle on the MFA’s chest-on-chest was replaced. As a result, the current urn finial supporting the eagle was conceived based on the design of the flanking urn-and-flame finials. The ionic pilaster capitals were restored based on both the MFA’s chest-on-chest and the Cogswell secretary bookcase in the collection of the Winterthur Museum (the distance between the pilaster and the molding above is identical on all three of these pieces). Each of the three aforementioned case pieces (the present chest-on-chest, the MFA example, and the Winterthur secretary bookcase) features a different fretwork design in the pediment frieze. The waist-molding fretwork design, however, is the same on both the MFA chest-on-chest and the Winterthur secretary bookcase. Consequently, the fretwork design was selected for the waist of the present piece.

Andersen’s shop also expertly patched and colored the holes from the inserted roundel escutcheons and the holes from previous brasses, resurfacing the finish on the front of the cases. The prior inappropriate brasses were replaced with eighteenth-century Birmingham brasses from an eighteenth-century English chest-on-chest, and were placed in the original post holes in the drawer fronts. Appropriate custom-cast escutcheons were reproduced based on illustrations in a period Birmingham hardware catalogue (in the Keno library collection).

Notes:

Few recent discoveries in American furniture parallel this bombé chest-on-chest attributed to Boston cabinetmaker John Cogswell. A sophisticated form made by one of the finest Boston cabinetmakers of the era, the present chest-on-chest represents the apogee of Boston Chippendale furniture. Two closely related examples survive in museum collections today: the Derby family chest-on-chest at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston1 and the Cogswell secretary bookcase at the Winterthur Museum.2 Together these three exceptional pieces demonstrate the conservative and simultaneously luxuriant nature of Boston taste that took a form, which had waned abroad, to new levels of development.

The bombé (or swelled base) form was introduced by imported pieces such as the English bombé double chest reportedly owned by Charles Apthorp (1698–1758) of Massachusetts.3 The earliest signed and dated bombé piece of furniture made in America is a secretary bookcase made by Benjamin Frothingham in 1753.4 The Frothingham secretary bookcase illustrates a combination of characteristics that remained popular for nearly three decades. This combination comprises a double-case piece which has a flat upper unit with flanking pilasters and a lower unit with a shaped front. On the Cogswell chests examined here, this combination is refined: The case sides are less bottom-heavy and abrupt, with a more gradual swelling. Three surviving chests-on-chests with this arrangement were probably made just north of Boston in the 1760s. They include a chest-on-chest in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg, another chest-on-chest probably from the same shop now at the Carnegie Museum, and a third chest-on-chest illustrated in Wallace Nutting’s Furniture Treasury, then in an Ipswich, Massachusetts, private collection.5

John Cogswell (1738–1819) moved to Boston from nearby Ipswich, Massachusetts, around 1760. As furniture scholars Robert Mussey and Ann Rogers Haley have discovered, Cogswell was one of the few outsiders to break into Boston’s relatively closed artisan community.6 In 1762, Cogswell married Abigail Gooding of Charlestown, Massachusetts, daughter of a six-generation family of artisans. It is likely that Cogswell trained with a member of the Gooding family, who presumably provided him entrance into Boston’s artisan community. Shortly after his marriage to Abigail, Cogswell became involved in the Caucus Club of Boston, a large and important union of artisans that wielded significant political power in the city. Cogswell rose to a certain amount of prominence and held town offices from 1763 to 1818 including constable, scavenger, surveyor of boards, surveyor of shingles, and surveyor of mahogany.7

Cogswell’s cabinetwork is perhaps most recognized on the Derby chest-on-chest at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which he signed, “Made by John/Cogswell in middle Street/Boston 1782.” Based on the construction and design features of the chest-on-chest, Rogers and Haley attribute at least thirteen pieces to Cogswell’s shop. The present chest-on-chest is a clear fourteenth. In their study, Mussey and Haley argue that by the early 1780s Cogswell (and at least one other cabinetmaker) updated traditional bombé forms by reducing the convex swell of the sides and fronts and by adding a double-serpentine edge to the façade. While the present chest-on-chest and its two close counterparts do not have double–serpentine façades as well as bombé sides, this feature is present on two desk-and-bookcases in the collection of Winterthur.8 The serpentine shape came into fashion in New England in the 1770s and was exceedingly fashionable by the 1780s. Generally, New England serpentine front furniture is indicative of the new Federal taste, but on Cogswell’s double-serpentine bombé case pieces it seems more expressive of the baroque design ethos. Nonetheless, the Derby family chest-on-chest is clearly labeled “1782,” and the Winterthur secretary bookcase retains a pencil inscription that reads “1786 AD” (on the underside of the bottom drawer), indicating that Cogswell continued to use the bombé shape without a double-serpentine façade well into the 1780s.

The present chest-on-chest, the MFA chest-on-chest, and the Winterthur secretary bookcase share great similarities in their design, decoration, and construction. As aforementioned they are each double-case pieces with rectilinear upper cases flanked by pilasters and coupled with shaped lower cases. All three examples are fitted with removable pediments constructed and designed in the same fashion with identical profiles (only the façades of these pediments rise up and scroll). The composition of design motifs used on the pediments also relate to one another. On all three a molded C-scroll with serrated edge outlines the negative space on either side of the plinth. Each also has a series of rocaille-type ruffles and vinelike foliage, all flanking a single arching leaf pendant with a central bead that decorates the central plinth. While the present chest-on-chest has a series of three rocaille ruffles on each side of the plinth, there are four on the Winterthur secretary pediment and five on the Derby chest-on-chest (if you count the one on the top toward the terminals). These applied carvings, which in some places are carved in three-quarters-inch-deep relief, are skillfully designed and carved. On the present chest-on-chest the largest rocaille ruffle artfully arches up off the surface and back down again.

The pediments on each of the three related examples feature a band of fretwork of equal size along the frieze. While the fretwork is composed of a linear diamond design together with a series of reverse curves, each one displays a slightly different pattern. The fretwork pattern at the waist of the chest-on-chest at the MFA and the secretary at Winterthur is the same, differing from the pattern on the frieze. As a result, this waist pattern was selected to replace the missing fretwork on the waist of the present chest-on chest.

According to Andersen, the pilasters on all three pieces are the same width and depth, each with five flutes. Probably a result of one template, even the space at the top (where the capital fits between the pilaster and the molding) is identical on all three upper cases; the applied capitals are therefore nearly interchangeable. In the lower cases, the bombé profiles are consistently swelled as well. A double molding at the base of all three examples creates a nice transition from the case into the compressed s-shaped cabriole legs. The claw-and-ball feet have raked talons and are carved with “hairy” talons, a favored treatment on Cogswell pieces (when the knees and brackets are carved). The brackets and knees of the present chest-on-chest and its two counterparts feature sophisticated carving consisting of C-scrolls and dense overlapping acanthus leaves articulated with shallow grooves like the rocaille shells at the pediment. The central pendants on the present chest-on-chest and the Derby chest-on-chest at the MFA closely relate in shape and are carved in a similarly laid-out pattern with a central piercing above a C-scroll over foliage. Here, the present chest-on-chest is arguably more successful: The size of the drop pendant on the Keno example is slightly smaller and better integrates with the stance and overall design of the lower case.

As Haley and Mussey discuss in their study of Cogswell furniture, the Cogswell shop used four different construction treatments for the interior surfaces of bombé case sides. The present chest-on-chest, the Winterthur secretary bookcase, and the Derby chest-on-chest at the MFA demonstrate two of these methods. One of the four treatments was to leave the inner case sides vertical while the exterior surface was shaped. The present chest-on-chest and the Winterthur secretary bookcase are constructed in this method. On these two pieces, the drawer sides are also vertically straight and the projecting drawer fronts fit into rabbets in the front edge of the case sides. The second method was to hollow-out the interior surface of the sides where the case swells to relieve the case of some mass. The Derby chest-on-chest at the MFA has hollowed-out inner case sides (two large hollows are cut on the inner surface of the sides where the case swells, leaving flat, unplaned surfaces at the top and bottom of each hollow to function as drawer guides). The drawer sides of the Derby chest-on-chest are also vertical rather than angled or curved, and the curved ends of the drawer fronts project beyond the drawer sides and fit into rabbets on the front edges of the case sides.9

Similar to the second method, the third method was to cut angled facets approximately parallel to the outer curve, while the fourth method was to saw the interior sides parallel to the outer curve. Of the pieces that Mussey and Haley examined in their study, Cogswell appears to have only used straight inner case sides on two pieces, which are both heavy double-case pieces like the present example. Perhaps he selected this construction method for the double-case pieces because of the mass of their upper section10 Nonetheless, the present chest-on-chest is consistent with Cogswell case construction.

The Keno chest-on-chest illustrates the most refined craftsmanship available in mid-eighteenth-century Boston. It attests to the competence and creativity of early American craftsmen as well as to the sophistication of their patrons. This chest-on-chest is arguably one of the best examples of a popular combination of forms, with scrolled bonnet, a linear upper case, and a shaped lower case. It is an exciting discovery attributed to a celebrated cabinetmaker, adding to a well-studied group of furniture from John Cogswell’s shop.

Provenance:

Charles Carroll of Doughoregan (1801–1862), grandson of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, to his daughter Helen Sophia Carroll, who married Charles Oliver O’Donnell (1822–1877), to their son John Charles O’Donnell to his son Hugh Roe O’Donnell and Lily Roosevelt (married 1930) to their son, the previous owner.

A special note on Provenance:

The present chest-on-chest came from a private Baltimore, Maryland, collection. The family believed that the chest was originally a Carroll family piece brought to the family by the previous owner’s great grandmother, Helen Sophia Carroll. It is believed that the chest-on-chest was owned by Helen’s father, Charles Carroll of Doughoregan. Coincidentally, an oral history maintained that the secretary bookcase at the Winterthur Museum belonged to the Carroll family of Carrollton. Another great coincidence is that the inscription in the Winterthur secretary bookcase was inappropriately read and published as “1786 AD Jackson.”11 In 1833, Charles Carroll of Doughoregan’s sister Louisa Catherine Carroll (b. 1809) married Isaac Rand Jackson (1804–1842) of Newburyport, Massachusetts. Isaac Rand Jackson’s father was Abraham Jackson (1748–1823), a prosperous merchant in Newburyport. Louisa Carroll and Isaac Rand Jackson resided in Philadelphia, which, if the Jackson inscription were correct, would have been a possible route south for this secretary bookcase. Nonetheless, it is fascinating that both pieces carry an oral history of Carroll family descent.

Dimensions:

Height to top of finial: 95”

Height to top of swan’s neck: 86 1/2”

Height to top of cornice: 79 1/16”

Height to top of case below pediment: 74 3/4”

Height to base molding: 9”

Height to bottom of drop pendant: 6 3/4”

Maximum width at cornice: 42 1/8”

Width of upper case: 38 1/4”

Width of lower case at top: 39 7/8”

Width of lower case at bombé: 43 5/8”

Width of knees: 43 7/8”

Width of feet: 44”

Depth at cornice: 21 1/2”

Depth at upper case: 19 3/8”

Depth at top of lower case: 21 1/8”

Depth at bombé area: 22 3/4”

Depth at knees: 23 3/8”

Depth at feet: 23 3/4”

Inventory number 1870.F00C

|

|

- Illustrated in a great number of publications including: Joseph Downs, “John Cogswell, Cabinetmaker,” The Magazine Antiques (April 1952): 322–324; Jonathan Fairbanks and Elizabeth Bidwell Bates, American Furniture: 1620 to the Present (New York: Richard Marek Publishers, 1981); Department of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Paul Revere’s Boston: 1735–1818 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1975), no. 265; Morrison H. Heckscher and Leslie Green Bowman, American Furniture, 1750–1775: Elegance in Ornament (New York, Harry N. Abrams, 1992), p. 143, no. 93; Wendy A. Cooper, In Praise of America: American Decorative Arts, 1650–1830, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), no. 33.

- Also illustrated in a number of publications including: Nancy E. Richards and Nancy Goyne Evans, New England Furniture at Winterthur (Winterthur, Delaware, A Winterthur Book, 1997), p. 46, no. 209; Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury (New York: Macmillan, 1954), no. 717; Joseph Downs, American Furniture (New York: Macmillan, 1952), fig. 228.

- This linen press is owned by the MFA, see Paul Revere’s Boston, p. 44.

- See Clement E. Conger and Alexandra Rollins, Treasures of State: Fine and Decorative Arts in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms of the U.S. Department of State (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1991), p. 94, no. 13. For further information on the development of bombé furniture in America, see Gilbert T. Vincent, “The Bombé Furniture of Boston,” Boston Furniture of the Eighteenth Century (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1972), pp. 137–196.

- For the Colonial Williamsburg example, see Barry A. Greenlaw, New England Furniture at Williamsburg (Williamsburg, Virginia, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1974), pp. 92–94, no. 81. For the example from the Carnegie Museum, see James Biddle, American Art from American Collections (exhibition catalogue) (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1963), p. 31, no. 57. For the example in a Massachusetts private collection, see Wallace Nutting, Furniture Treasury, vol. III (New York: Macmillan, 1933), fig. 277.

- Robert Mussey and Anne Rogers Haley, “John Cogswell and Boston Bombé Furniture: Thirty–Five Years of Revolution in Politics and Design,” American Furniture 1994, Luke Beckerdite, ed. (Milwaukee, WI, The Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 73–105.

- See Mussey and Haley, pp. 79–80, and Richards and Evans, p. 447.

- See Mussey and Haley, p. 90, figs. 24–25, and Richards and Evans, pp. 492–493, no. 225.

- For further discussion, see Mussey and Haley, p. 83.

- See Mussey and Haley’s chart, pp. 104–105.

- Mussey and Haley, pp. 88,105.

|

|

|