|

| Home | Articles | Pride of Place: Architecture in American Textiles |

|

|

by Laura Fisher

|

A charming and accessible way to appreciate American architectural history is to explore textile folk art that contains images of buildings. For centuries, folk artists have refined and elaborated on the nostalgic, iconic allure of our architectural past, and thus portraits of buildings abound in this nation’s artistic heritage.

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Sampler worked by Hannah L. Hancock, Burlington County, N. J., dated 1840. 17-3/4 x 20-1/2 in. Courtesy of M. Finkel & Daughter.

|

Made of fabric, wood, metal, or paper, representations of the built environment fall into two categories: realistic images of specific structures; and symbolic allusions to home, religion, industry, community. Buildings are universal, welcoming, and offer shelter. They are a central component of people’s lives and thus a natural image to select and record. Whether showing a family residence, church, public building, or ancient structure from mythology or literature, folk art depicting architectural renderings communicates a heartfelt effort to represent a sense of place.

In folk textiles, it was primarily women and young girls who either chronicled their surroundings or fantasized about their concepts of home, creating realistic or idealized structures that represented both a necessity in life (a roof over one’s head) as well as the female domain. As in other areas of folk art, there are unique, individualized examples to be found, but there are also folk textiles that were made from patterns. Though these designs were generally mass-produced, this latter group can still bear the artistic imprint of the person who worked the pattern. What follows are some examples of how architecture was expressed, in American antique needlework, quilts, and hooked rugs.

|

|

|

|

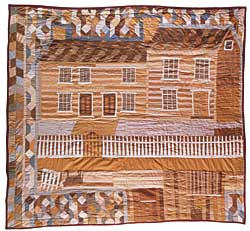

Fig. 2: Log farmhouse and barnyard pieced and appliquéd quilt by Sarah Goforth, Weymouth, N. J., ca. 1870–1880. Cotton. 70 x 66 in. Collection of Laura Fisher.

|

Needlework

Some of the earliest images of architecture in American textiles are seen in samplers and silkwork pictures (Fig. 1) rendered by young girls who attended schools in which they learned sewing skills. The name of the student, schoolmistress, and location of the academy were sometimes incorporated into the overall design of these works. As a result, structures such as the first congregational church in Providence, Rhode Island; St. Joseph’s Academy in Maryland; and the Hancock House in Boston, Massachusetts, are identifiable.

There are scores of needlework pictures, however, about which no documentation exists, frustrating the search to uncover specific information about the structures. Trying to determine a needlework’s origin based on the style of the architecture can be misleading, given the challenge of differentiating between, for example, an English Georgian house and its colonial counterpart when worked in thread. Building designs can, however, provide information relating to the age of the work, even if it is a compilation or generic structure.

Some needleworks have characteristics that link them with a particular instructor. Though stitched by different hands, the images depict exactly the same building, decorative elements, and format. In such circumstances, the structure may be the school itself or a public building known to the needleworker, or the teacher may have provided print sources for the students to copy. A challenge to the collector is to locate samplers featuring the same building, or to collect building types recorded in samplers from schools in different states, so as to compare the range of architectural images.

|

|

|

|

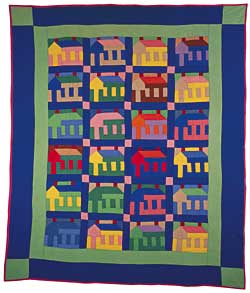

Fig. 3: “The Old Homestead,” pieced quilt, unknown maker, probably Ohio, ca. 1940s. Cotton. 80 x 70 in. Collection of Laura Fisher.

|

Quilts

The universality of quilts—pieced, appliquéd, or whole cloth—pays tribute to the comfort they bring to the home, on both a physical and an emotional level. Given their elemental connection to the concept of protection, it seems only natural that images of the home would become part of the decorative vocabulary. Houses and buildings primarily appear on quilts in the form of repetitive pieced or appliquéd blocks of a single image or as the central elements on pictorial quilts.

Whether a communal enterprise engaging women from a neighborhood, or a solitary expression, quilts offer a prominent surface on which to create a decorative scheme, a story, or a visual record of one’s surroundings. The unusual pictorial quilt in figure 2 was made by Sarah Goforth, and most likely represents her home in Weymouth, New Jersey. She fashioned in cloth the brickwork, roof shingles, clapboards, and a white picket fence. Portraying both sides of the dirt road in front of the farmstead, she provided a dual perspective of the site. In both the details and the monumental size of the house, this portrait is a personalized statement symbolically emphasizing the importance of home to the maker.

Aside from such unique images as this one, numerous house patterns were published from the late nineteenth century onward that quilt makers could purchase from catalogues or periodicals. Rival firms borrowed design ideas from one another, particularly the favorite patterns “House on the Hill,” “Old Kentucky Home,” “Honeymoon Cottage,” “Schoolhouse,” and the frequently seen “Log Cabin.” The most familiar house design consisted of pieces of colored material combined in a geometric pattern that created the visual framework for a building. The basic pattern could be modified or embellished by the quilter with materials such as lace at the windows or embroidered windowpanes to personalize what was an otherwise generic shape.

The quilt in figure 3 was made using pattern number 108, “The Old Homestead,” published and sold through the Ladies Art Company catalogues from the late 1800s into the twentieth century. Rather than create a conventional look by using earth tones or calicoes, a bold palette was selected, creating a stunning play of contrasting colors. As with other quilts based on purchased patterns, through depicting an idealized image of home, the emphasis was on creating a visual scheme.

|

|

|

|

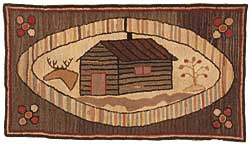

Fig. 4: Log cabin hooked rug with deer head, maker unknown, New England, ca. 1920. Wool yarn on burlap. 26 x 48 in. Collection of Laura Fisher.

|

Hooked Rugs

Anyone with fabric or rags, a foundation material like burlap or canvas, and a bent nail could hook a rug. Made in America and Canada by the early 1800s, their purpose was utilitarian rather than for display, perhaps the reason why they were infrequently signed, unlike quilts and needlework.

All types of buildings were depicted in this versatile medium—cottages in landscapes, log cabins, mill buildings, farmsteads, churches, town halls, court houses, and so on. Many rugs were of individual design. Others were hooked from pre-stamped burlap patterns marketed from the late nineteenth century by Edward Sands Frost of Maine, and Ebenezer Ross of Ohio, the principal pattern entrepreneurs at the time, and in the early twentieth century by companies such as Ralph E. Burnham of Massachusetts, Garrett’s of Nova Scotia, and Heirloom Rug Patterns of Rhode Island. Still other collectible rugs are the product of cottage industries organized to generate income for rural families, or to provide a creative outlet for participants. By producing and marketing rugs, the Grenfell Mission in Labrador and Newfoundland, Canada; the Maine Seacoast Missionary Society, and other groups made lasting contributions to this area of folk art collecting.

The rug in figure 4 depicting a log cabin with deer head dates from the 1920s. While the oval framed center, corner motifs, and narrow hooked borders suggest a stamped pattern, the idiosyncratic design seems to indicate a personal interpretation influenced by mass-produced examples. The rendering of the log cabin is generic, possibly, in part, because precise architectural detailing was more challenging in this medium.

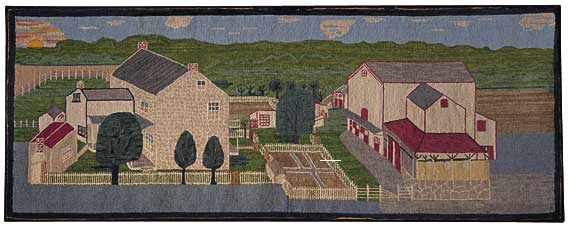

In contrast, the portrait of an Amish farm (Fig. 5) features realistically rendered architectural detailing, even using proportion and perspective. A stunning visual study in the folk art tradition, this rug provides insight into building materials and structural relationships based on the needs of this agrarian community, thus underscoring its importance as an historical document.

The architectural record preserved in folk textiles is quite broad and spans centuries, lifestyles, economic levels, and artistic trends. As Gerard Wertkin, Director of the American Folk Art Museum has said, “…folk artists have found a potent symbol in these images…. That sense of a rational built environment…is at the heart of the American Experience,”1

|

Fig. 5: Pennsylvania Amish farmstead hooked rug, Mamie Smoker, Lancaster County, Penn., ca. 1930s. Wool on burlap. 40 x 103 in. Collection of Dr. Leslie Williamson.

|

|

The content for this article is adapted from Home Sweet Home: The House in American Folk Art (Rizzoli, 2001), authored by Laura Fisher and Deborah Harding. It is available in bookstores and at Laura Fisher/Antique Quilts & Americana.

Laura Fisher is the owner of the New York City gallery Laura Fisher/Antique Quilts & Americana. In addition to Home Sweet Home (2001), she is the author of Quilts of Illusion (1988). She lectures and contributes to Country Living Magazine, and is a frequent guest on Martha Stewart Living. Her next publication will be the 2004 Quilt Engagement Desk Calendar (Barnes & Noble).

|

|

1. Harding and Fisher, Home Sweet Home: The House in American Folk Art (New York, 2001), forward.

|

|

|

|