|

|

Over the past dozen years, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts has been actively collecting ceramics that together relay the history of art and design. To this end, the Institute continues to develop its collection of ceramics; those illustrated here are a selection representing the craftsmanship of the British Isles, Europe, and Asia. The vast majority of these objects date from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries and have recently come to the museum through the support of passionate collectors in the Minneapolis and St. Paul communities.

One of the most significant recent additions is the Modernism Collection, gift of Norwest Bank, Minnesota, which has provided an opportunity for the Institute to interpret early modern styles from art nouveau to art deco. The museum’s interests have further expanded to include the post-World War II movements. This vision dovetails with the Institute’s commitment to studio pottery and its mission to promote the Twin Cities as the center for contemporary ceramics in the Midwest. Indeed, the museum’s own growing collection of Midwest and Upper Mississippi River contemporary pottery is placed in the context of twentieth-century utilitarian and sculptural ceramics through comparison with recently added works by Beatrice Wood, Robert Arneson, and Peter Voulkos.1 Illustrated here are several of the most recent ceramic acquisitions that provide a tour of three centuries of style.2

|

|

|

Punch bowl, Chinese (export), ca. 1762. Hard-paste porcelain with enamel and gilt decoration. Diam. 121/2 in. Gift of Leo A. and Doris Hodroff, 1995.

Inset: Banknote painted on bottom interior.

|

Occidental cultures have long admired the translucent hard-paste porcelains from China. To satisfy the demand for these wares, the Chinese exported ceramics in great numbers to Europe and America from the 1500s through the 1800s. Among the decorative elements that attracted Western patrons were finely decorated floral designs, examples of which appear in grisaille paint with gilt accents on the sides of this punch bowl. As punch bowls were often custom-ordered and commemorative, they frequently displayed coats-of-arms and insignia, the designs being provided to the Chinese as models. This punch bowl is handpainted with the pattern of a Swedish banknote dated 1762, yet, amusingly, the image would have been discovered only upon reaching the bottom of the bowl. It is one of many significant examples of Chinese export porcelain given by Leo and Doris Hodroff, whose close relationship with the museum has resulted in the publication of The Choice of the Private Trader: The Private Market in Chinese Export Porcelain illustrated from the Hodroff Collection (The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1994).

|

|

|

|

Pair of candlesticks, Henry Delamain (1713–1757), owner of World’s End Pottery (1735–1771), Dublin, Ireland, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware with blue and enamel decoration. H. 95/16 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. George R. Steiner, 1997.

|

There are few extant examples of eighteenth-century Dublin polychrome tin-glazed earthenware. Indeed, these are two of only three such candlesticks from Dublin known to exist. Vertical seams reveal that they were created using a two-part mold. The pattern is based on the design of opaque-white twist-stemmed glass candlesticks then being made in the Staffordshire region of England. The spiral design on the stems presented the appearance that the tin-glazed examples were hand-thrown on a wheel. Similar to related opaque glass candlesticks, the raised lip on these Dublin sticks indicates they were intended to hold metal liners, now missing, for candles. The delicately painted floral sprigs appear on similar Dublin earthenware, suggesting that candlesticks with these elements were intended for sale en suite with other tableware.3

|

|

|

|

Garniture, Jacobus Halder (painter), De Griekse A (Greek A) factory (manufacturer), Delft, the Netherlands, ca. 1765. Tin glazed-earthenware with blue decoration. H. 161/4 in. Gift of Samuel and Patricia McCullough in honor of the Decorative Arts Council, 2000.

|

Intended for display atop a mantel or kasten (wardrobe), this ambitious rococo garniture set is a Dutch version of Chinese porcelain exported to Holland through the Dutch East India Company. The town of Delft captured a share of this market by producing earthenware predominantly painted with cobalt blue decoration and coated with a lead-tin glaze. When fired, the glaze turned opaque, resulting in an object that imitated the more expensive Chinese porcelain.

The garniture is decorated with mirror images on each side depicting a woodcutter amid a landscape of trees and grasses. The scenes are framed in scroll-shaped cartouches balanced by naturalistic rococo designs of shells, flowers, and latticework. The Fu-dog finials and ginger-jar shaped vases demonstrate the taste for chinoiserie, the Western interpretation of Chinese art and culture, which served as one of the basic tenets of the rococo style. The combination of Asian and Nordic imagery captures the essence of the Dutch marketplace during this period in time. Americana collectors Sam and Patty McCullough donated this garniture to the museum to provide a valuable comparison with the Steiner collection of British tin-glazed earthenware.

|

|

|

|

Kettle, Leeds Pottery (ca. 1758-1820), Yorkshire, England, ca. 1770. Glazed earthenware with slip decoration. H. 1013/16 in. Gift of Mrs. Eunice Dwan, 2001.

|

This kettle was most likely used for pouring hot water into teapots as it lacks a strainer in its spout for catching tea leaves. The double twist branch-shaped handles that terminate in stylized leaves, and the molded female mask under the spout are characteristic of ceramics made by Leeds Pottery. The blending of naturalism and asymmetry were hallmarks of the rococo style, which was still popular in England into the late eighteenth century. However, a penchant for the geometric ideals of the neoclassicism that followed is conveyed in the vertical striped banding on the sides of the kettle and lid, accomplished through slip decoration.

|

|

|

|

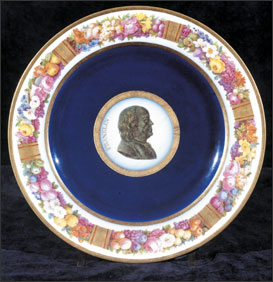

Plate with portrait of Benjamin Franklin, Manufacture Nationale de Sèvres (1756–present), Sèvres, France, 1801–1802. Hard-paste porcelain with blue and enamel decoration. D. 81/4 in. Gift of the Decorative Arts Council with funds from the 2001 Antiques Show and Sale, 2001.

|

Originally part of a dinner service, this neoclassical plate is a testament to the skilled decorative painters of the Sèvres factory. Based on the manner of execution, at least three artists were responsible for rendering the polychrome garland of fruits and flowers, the rich cobalt blue base, and the bronzed head of Benjamin Franklin. Sèvres produced various images of Franklin, perhaps inspired by the occasion when he dined with the directors of the Sèvres decorative studios in 1777.

The first American ambassador to France, Franklin was beloved there for his wisdom and diplomacy. He embraced French culture and, upon his return to Philadelphia in 1785, promoted the ideals of French taste in household furnishings throughout Federal America. The account books at the factory archives confirm that Sèvres produced only a few plates in this neoclassical pattern, of which this is the only one known to survive.4

|

|

|

Encaustic tile, Minton’s China Works (1830–1918), Stoke-on-Trent, England, ca. 1865. Tile marked Minton & Co. Pressed clay and incised slip decoration. L. 6, W. 6, H. 1 in. Gift of Christopher Monkhouse in honor of Evan and Naomi Maurer, 2001.

|

In 1830, Herbert Minton began making tiles by the encaustic process in a manner similar to those made in medieval Europe. Encaustic tiles were immediately popular as they evoked the dramatic and romantic Gothic Revival patterns promoted by designers like A.W.N. Pugin (1812–1852) and Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852). The Gothic Revival also had intellectual overtones, making the tiles suitable for even the president of the United States: An inscription on this bold tile suggests that it was one of many installed in the White House in the 1860s or 1870s and removed during the McKim, Mead & White restoration of the mansion in 1902.

The encaustic process involved compressing a malleable clay tile into a relief pattern, resulting in an intaglio channeled design on the surface of the object. After a colored slip was poured into the channels, the tile was fired and cleaned to reveal a smooth appearance, often ornamented with a vocabulary of Middle Ages motifs.5 This tile is part of several groups of American and English tiles recently given to the museum, many of which may be seen with other Twin Cities tile collections in the exhibition Minton to Malibu: The Art of Glazed Tiles (through November 17, 2002).

|

|

|

Bodenvase (floorvase), Gustav Heinkel (1907–1945), (designer), Karlsruhe State Maloyka Manufaktur, (manufacturer), Karlsruhe, Germany, 1930. Glazed stoneware with enamel decoration. H. 27 in. The Modernism Collection; gift of Norwest Bank, Minnesota, 1998.

|

Gustav Heinkel started his career in Germany at the Karlsruhe State Maloyka Manufaktur where he remained until 1944. While there he developed his expertise in the Bauhaus principals of abstract and geometric design apparent in this vase. The atmospheric decoration incorporates hand-drawn shapes, vivid flowing colors, and speckled paint on a crackle-glaze surface. It speaks to Heinkel’s command of the ceramic medium as well as to his expressive painting technique. Shortly after the vase was completed, a member of the E. L. King family of Minnesota purchased it for the redecorating campaign of Rockledge, their 1912 Arts and Crafts home along the Mississippi River.6

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts has been highlighting its ceramics collections this yearin several exhibitions to celebrate the theme of the nineteenth annual Decorative Arts Council Antiques Show and Sale, Meissen to MacKenzie: Three Centuries of Creating and Collecting Ceramics. Many of the objects illustrated are on display at the Institute throughout the fall.

All photographs courtesy of The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Jason T. Busch is Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts, Sculpture, and Architecture at The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

1 Work by these makers can be seen in the exhibition California Ceramics: Functionalism to Funk, on view through October 13, 2002.

2 I wish to thank my colleagues in the Department of Architecture, Design, Decorative Arts, Craft and Sculpture, especially Christopher Monkhouse, the James Ford Bell Curator, and David Ryan, Curator of Design, for their encouragement and advice in publishing this article.

3 Peter Francis, Irish Delftware: An Illustrated History (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 2000), 116–117. Peter Francis generously shared his thoughtson the museum’s Irish delftware candlesticks.

4 I wish to thank Deborah Gage of Deborah Gage Works of Art for providing information on the design of the plate.

5 For more information on Minton tiles, see Julian Barnard, Victorian Ceramic Tiles (New York: Christie’s International Collectors Series, 1979).

6 Rockledge was destroyed in 1985. For more information on Heinkel and Bauhaus objects in the Norwest Collection, see Alastair Duncan and David Ryan, Modernist Design: 1880–1940 (Minneapolis: Norwest Corporation and Antiques Collectors’ Club, 1998).

|

|

|