|

| Home | Articles | Odd, Old & Unusual: Intriguing Forms in Delftware |

|

When most people think of delftware, the ubiquitous plate, pot, or punch bowl often comes to mind. Occasionally other pieces of delftware are encountered on the antiques market whose purpose is more obscure and foreign to our twenty-first century way of life. Many of these unusual objects begin to make sense when placed in their social, cultural, and historical context.

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Posset pot, London or Bristol, England, ca. 1710–1730. Tin-glazed earthenware decorated in cobalt blue, green, and red. H. 93/4" (24.77 cm), D. 97/8" (25.1 cm), Diam. 71/4" (18.42 cm). Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc. 63.179.

|

One of the strangest and most fascinating forms created in delftware was the posset pot (Fig. 1). The versatile beverage known as posset was most often served in these two-handled, spouted drinking vessels with a cover. Over time, the shape of posset pots progressed from simple, straight-sided forms to curvilinear vessels with elaborate ornamentation. The most outlandish examples, fashioned with three-dimensional snakes, birds, and crowns, appeared in the mid-1670s and 1680s. Most pots produced in the early eighteenth century returned to a simpler form of decoration while retaining the bulbous baroque shape.

Dictionaries and cooking manuals mention the beverage posset from 1573 onward, but the drink was most popular in the seventeenth century. In a typical recipe, several eggs were beaten and mixed with sugar, spices, and sack (a general name for a class of white wines imported from Spain and the Canaries) or ale. After straining the resulting mixture, boiling cream was added. The acidic alcohol curdled the hot cream, forming a frothy layer of custard floating on top. Separation of the curd from the whey required about two or three hours, during which time the posset usually rested near a fire. One seventeenth-century manuscript receipt book advised surrounding the posset with cushions to prevent it from cooling too much. A good posset had three parts to it: “If it be right made it will be snow on ye top, thike in the middle and clear liquor at ye bottome.”1 The floating custard portion of posset was usually eaten with a spoon, while the liquid was sucked from the bottom of the pot through the central spout.

Convivial gatherings often featured posset. Samuel Pepys, England’s famous diarist, wrote, “At night to supper; had a good sack-posset and cold meat and sent my guests away about ten a-clock at night.”2 Pepys also chose to serve the beverage at his Twelfth Night (the evening before Epiphany) celebration. He observed, “By and by to my house to a very good supper, and mighty merry and good music playing; and after supper to dancing and singing till about 12 at night; and then we had a good sack-posset for them and an excellent Cake.”3

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Puzzle jug, Liverpool or London, England, ca. 1760. Tin-glazed earthenware decorated in cobalt blue. H. 75/8" (19.38 cm), D. 71/8" (18.11 cm), Diam. 33/8" (8.89 cm). Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc.; John W. and Christiana G. P. Batdorf Endowment Fund for Museum Acquisitions. 2000.64. Inscription on belly in cobalt blue: Here gentlemen Come try yr Skill/ Ile hold a wager, if you will/ That you don’t drink this liqr all,/ Without you Spill or let Some fall.

|

Valued for its strengthening and restorative properties, posset was a traditional drink at weddings from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. The “benediction” posset toasted the bride and groom before they retired to the nuptial bed. In 1713, Samuel Sewall, a Boston judge and diarist, recorded drinking sack-posset at the wedding of his niece Susan Sewall to Aaron Porter. Sewall recalled that “Mr. Noyes made a Speech, said Love was the Sugar to sweeten every Condition in the married Relation. Pray’d once…After Sack-Posset, & c. Sung the 45th Psalm from the 8th verse to the end.”4

Beyond its popularity as a social drink, posset was valued as a remedy for common ailments and afflictions. Pepys drank posset when he sought relief for a cold. He stated that “it is a cold, which God Almighty in justice did give me while I sat lewdly sporting with Mrs. Lane the other day with the broken window in my neck. I went to bed with a posset, being very melancholy.5” But by the mid-eighteenth century the consumption of posset and the use of posset pots had declined. Beverages such as punch and tea became much more popular and needed little in the way of elaborate preparation.

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Fuddling cup, London, England, ca. 1630–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 31/2" (8.89 cm), D. 43/4" (12.07 cm). Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc. 58.057.

|

Another drinking vessel that confounds modern onlookers is the puzzle jug (Fig. 2). These vessels, manufactured in many countries and in all types of earthenware and stoneware, date from as early as the Middle Ages. Delftware puzzle jugs achieved great popularity in both England and northern Europe, and were widely used in taverns and clubs. The unwitting drinker faced the “puzzle” of drinking from the vessel without spilling its contents through the perforations. This could be accomplished only by covering all but one of the spouts and a small hole under the handle, then sucking the liquid out of the remaining spout. The puzzle jug was a tour de force of the potter’s art, and the preserve of the most accomplished potter. The creation of a puzzle jug required great virtuosity, because a potter threw a hollow handle that linked the container with a hollow ring at the top of the vessel. The inscriptions on puzzle jugs typically dare or challenge the drinker. The one shown here (see previous page) bears the most common version of drinking rhyme and implies a wager.

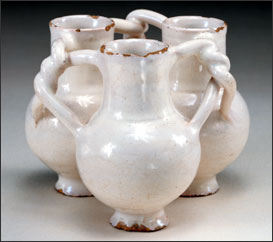

Another variant on this drinking game theme is seen in the fuddling cup (Fig. 3). The Oxford English Dictionary defines fuddle, a word in use by the late sixteenth century, as “to confuse with, or as with, drink.” Although there is no evidence that the term fuddling cup had entered the language in the seventeenth century, it has long been used to describe a vessel of three or more containers with internal openings and intertwined handles.6 The modest size of the containers surely deceived uninitiated drinkers who were encouraged to drain the cup dry. In reality, they would consume the liquor in all three, becoming more drunk or befuddled than anticipated.

A three-part cup in the Taunton Museum, Somerset, England, with the inscription “THREE MERY BOYS” has led scholars to suggest that the individual cups were called “boys.” Similarly, a fuddling cup formerly in the Louis Lipski collection is labeled “DRYNCK ALL BOYSE.” Boy may be a corruption of the French conjugated verb bois, to drink, or it may derive from earlier drinking cups decorated with faces on each of the cups.7

|

|

|

|

|

Figs. 4a, b: Monteith, probably Holland or possibly England (London or Bristol), ca. 1700–1710. Tin-glazed earthenware decorated in cobalt blue. Inscribed on base in cobalt blue, “2” and other marks. H. 63/4" (17.15 cm), Diam. 131/4" (33.66 cm). Courtesy of Historic Deerfield, Inc. 67.103.

|

In the late seventeenth century, the preference for serving wines cold led to placing glasses in ice water before use. Several forms—basins, fountains, and cisterns—were developed for this specific purpose. Monteiths (Figs. 4a, b), notched basins that allowed footed glasses to hang in chilled water, first appeared in 1683. The Oxford diarist Anthony Wood wrote that “this yeare in the summer time came up a vessel or bason notched at the brims to let drinking glasses hang there by the foot so that the body or drinking place might hang in the water to coole them. Such a bason was called a ‘Monteigh,’ from a fantastical Scot called ‘Monsieur Monteigh,’ who at that time or a little before wore the bottome of his cloake or coate so notched uuuu.”8 These large bowls were usually made of silver, although pewter, glass, pottery, and porcelain monteiths survive. Their production had nearly ceased by the 1730s. Dr. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (London, 1755) described a monteith, then long out of fashion, as “a vessel in which glasses are washed,” the purpose over time having extended beyond just cooling. By the mid-eighteenth century the function of the monteith had been replaced by individual wineglass coolers and by the stylishly French verriere, essentially smaller versions of the monteith intended for the table.

These objects and more are featured in the exhibition Delicate Deception: Delftware at Historic Deerfield, 1600– 1800, on view in the Flynt Center of Early New England Life at Historic Deerfield until November 30, 2002. The exhibition is accompanied by a full-color catalogue featuring three essays on collecting delftware at Historic Deerfield, the history and manufacture of delftware, and delftware for the Connecticut River Valley, in addition to ninety-seven detailed object entries.

Amanda Lange is an Associate Curator at Historic Deerfield, Inc., Deerfield, Massachusetts. She is the author of Delftware at Historic Deerfield 1600–1800 (2001).

1 Quoted in Peter B. Brown and Marla H. Schwartz, Come Drink the Bowl Dry (York, England: The York Civic Trust, 1996), 65.

2 Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds., The Diary of Samuel Pepys, 8 vols. (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1976); 4: 14.

3 Ibid., 13.

4 M. Halsey Thomas, ed., The Diary of Samuel Sewall, 1674–1729, 2 vols. (New York: Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1973); 2: 730–731.

5 Latham and Matthews, eds., The Diary of Samuel Pepys; 4: 318–319.

6 According to Richard Coleman-Smith and T. Pearson, Excavations in the Donyatt Potteries (Chichester, England: Phillimore & Co., Ltd., 1988), 40,

an early reference to the form dates to 1791, when the Reverend J. Collinson wrote of earthenware manufacture in Donyatt, Somerset: “The chief productions of the Crock Street potteries would appear to have been Jolly Boys or Fuddling Cups, which were three drinking cups joined in one so that they could all three be drunk from at the same time.” Quoted in Leslie Grigsby

et al, The Longridge Collection of English Slipware and Delftware, 2 vols. (London: Jonathan Horne Publications, 2000); 2: 316, D290, D291.

7 Michael Archer, Delftware: The Tin-Glazed Earthenware of the British Isles (London: The Stationery Office in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), p. 256; David Gaimster, German Stoneware, 1200–1900 (London: The British Museum Press, 1997), 228–229, pl. 77.

8 Andrew Clark, ed., The Life and Times of Anthony Wood, Antiquary, of Oxford, 1632–1695, Described by Himself, 5 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, for Oxford Historical Society, 1891–1900); 3:84.

|

|

|

|