|

|

|

Wine has matured alongside human institutions such as religion and the arts, and, therefore, has been viewed to have religious, spiritual, and ritual significance. The connection between wine and spirituality, artistic expression and social customs may be observed in any culture of any epoch. In studying the traditional uses of wine in China, we confront the mystique of antiquity and basic human spirituality, but we also encounter a living tradition. This article is intended to open a window on Chinese culture through wine and wine-related materials as their history is traced through the dynasties. Wine has matured alongside human institutions such as religion and the arts, and, therefore, has been viewed to have religious, spiritual, and ritual significance. The connection between wine and spirituality, artistic expression and social customs may be observed in any culture of any epoch. In studying the traditional uses of wine in China, we confront the mystique of antiquity and basic human spirituality, but we also encounter a living tradition. This article is intended to open a window on Chinese culture through wine and wine-related materials as their history is traced through the dynasties.

Distillation originated in China as early as the Yangshao culture (5000–3000 B.C.) in the Neolithic period.1 The classic bronze wine vessel forms of the Shang (ca. 1766–1122 B.C.) and Zhou (1122–256 B.C.) periods actually evolved from the pottery and horn vessels used for prehistoric rituals, cooking, and serving.2 These forms developed from primitive prototypes during the Xia dynasty (ca. 2500–ca. 1766 B.C.) [Fig. 1] and became increasingly ornate during the Shang, when the attachment of figures and animals in relief and in the round as finials and handles, as well as entire drinking vessels made to resemble animal forms, were introduced. Shang oracle bone inscriptions indicate that a wide variety of ritualistic ceremonies involved the consumption of wine, some of which are reflected by the decorative animal elements on the wine vessels. While wine was important in a religious context, with the relatively high standard of living garnered from agricultural pursuits among the ruling class, drinking also became a recreational activity that led to debauchery and extravagant lifestyles.

Wine retained a significant ritual role in the Zhou period. Opulent furnishings found in royal tombs demonstrate that the Zhou dynasty resembled the Shang in their enjoyment of wealth as well as in their devotion to similar religious beliefs and practices; in contrast to their late Shang predecessors, however, the Zhou dynasty prided themselves on their sobriety and piety. In the Zhou period, their own stylistic signature was interpreted on their bronzes, which tend to be less delicate in their decoration than Shang examples. Wine retained a significant ritual role in the Zhou period. Opulent furnishings found in royal tombs demonstrate that the Zhou dynasty resembled the Shang in their enjoyment of wealth as well as in their devotion to similar religious beliefs and practices; in contrast to their late Shang predecessors, however, the Zhou dynasty prided themselves on their sobriety and piety. In the Zhou period, their own stylistic signature was interpreted on their bronzes, which tend to be less delicate in their decoration than Shang examples.

Archaeological finds attest to the prominent role wine played in ceremonies as reflected in the storage vessels found at burial sites [Figs. 2, 3]. The literature of the period also contains some of the earliest descriptions of the precise use of wine and wine-related paraphernalia. Zhou texts, for instance, describe different varieties of alcoholic drink and their ingredients and production methods. Generally speaking, at this point there were two primary kinds of wine available in China: one made from rice in the South and one from millet in the North.

The Han dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220) ushered in political and economic stability in the wake of the social upheaval accompanied by the end of any dynasty. The unified empire expanded into Central Asia. Emperor Wudi (141–87 B.C.) sent the official Zhang Qian on a diplomatic mission whereby he discovered cultures with valuable goods to trade in exchange for silk. Opening the fabled “Silk Road,” he is also credited with the introduction of grapes and grape wines. The introduction of this new beverage resulted in the opening of wine shops in the Han capital Chang’an, where exotic food and wines were available to the privileged class.

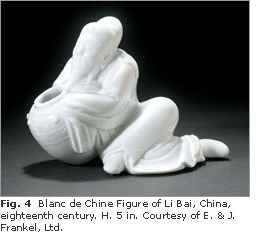

During the Tang dynasty (618–906), Silk Road trade brought in goods as well as an increased influx of foreign ideas and artistic influences. In cosmopolitan Chang’an, grape wine from the West became fashionable not only among the elite but also among the masses. The popularity of the beverage was reflected in the images of grapes that embellished wine vessels, influences absorbed from Central Asia and the Middle East. Li Bai (701–762), regarded as the finest poet of the Chinese language, frequented the wine shops of Chang’an. His poetry expresses his love of solitude, wine, and the transcendent beauty of nature. He and his friend Du Fu (712–770) were the voice of this golden age; the depiction of Li Bai in Chinese art immortalized him in later dynasties [Fig 4].

|

More than in any earlier age, Tang dynasty wine connoisseurship integrated all the senses, not merely taste and smell. The sense of sight, for example, was stimulated by the wine’s color, and the frequent reference to wine and its colors in Tang poetry brought wine into the realm of sound as well. Green was a favorite wine hue, with its allusion to pale green bamboo leaves. Furthering connections with the senses, green wines were served in red- and purple-glazed cups carefully chosen to enhance the visual effect. More than in any earlier age, Tang dynasty wine connoisseurship integrated all the senses, not merely taste and smell. The sense of sight, for example, was stimulated by the wine’s color, and the frequent reference to wine and its colors in Tang poetry brought wine into the realm of sound as well. Green was a favorite wine hue, with its allusion to pale green bamboo leaves. Furthering connections with the senses, green wines were served in red- and purple-glazed cups carefully chosen to enhance the visual effect.

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), connoisseurship in all the arts extended to cuisine and wine. The connection between art and wine became so close that wine shops hosted literati discussions about the finesse of porcelain glazes, paintings, and poetry. The most elegant wine shops also became art galleries, especially in the capital. Sometimes literati patrons ran out of money and left paintings in lieu of payment. While elaborately decorated restaurants known as “wine palaces” catered to the intelligentsia and upper classes, wine shops flourished at all levels of society, offering various forms of entertainment—from wine brothels to roadside tents set up for workers.

During the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) there was increased contact between the East and West resulting in the assimilation of various artistic influences [Fig. 5]. This cultural exchange was decreased significantly, however, when after nearly a century of foreign domination, Zhu Yuanzhang’s peasant rebellion resulted in the formation of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Although one of China’s most prosperous periods, foreign influences were frequently limited by the narrow scope of the regime. The one exception was the reign of Yongle (1402–1424), whose merchant fleet conducted exploration, trade, and diplomacy. These voyages brought treasures from as far as Africa and Arabia, including large quantities of foreign wine. Subsequent emperors disbanded the fleet, plunging China back into self-imposed isolationism and a gradual decline as a world power. During the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) there was increased contact between the East and West resulting in the assimilation of various artistic influences [Fig. 5]. This cultural exchange was decreased significantly, however, when after nearly a century of foreign domination, Zhu Yuanzhang’s peasant rebellion resulted in the formation of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Although one of China’s most prosperous periods, foreign influences were frequently limited by the narrow scope of the regime. The one exception was the reign of Yongle (1402–1424), whose merchant fleet conducted exploration, trade, and diplomacy. These voyages brought treasures from as far as Africa and Arabia, including large quantities of foreign wine. Subsequent emperors disbanded the fleet, plunging China back into self-imposed isolationism and a gradual decline as a world power.

A reaction to the period that preceded it, the Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1912) patronized traditional arts to assert their legitimacy as rulers of China. For example, Emperor Qianlong (1736–1796) embraced the traditions of Chinese antiquity. It was during his reign that the examination and classification of archaic bronzes, which had been sorely neglected since the Song dynasty, gained renewed interest. Qianlong was a connoisseur of the arts. With over a million objects in his collection, his taste influenced the production of imperial workshops and the porcelain kilns. His personal collection of European enamels, clocks, and watches demonstrates his taste for foreign art as well. He held great admiration for his royal counterpart in France, Louis XVI, and the influence of European rococo style found expression in the highly refined media and surface decoration of eighteenth-century imperial porcelains [Fig. 6]. This trend reflects perhaps the greatest period of foreign influence on Chinese art since the Tang dynasty.

Court decadence, bureaucratic corruption, and encroachment by foreign forces, however, all contributed to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912. Yet even the violent and turbulent changes experienced by China and the Chinese people could not efface completely the deep-rooted traditions of the culture. We may not find the grand ceremonies of the imperial ancestor cult performed anymore, but the treasured relics of ancient rites are studied and appreciated. The love of wine, not only as a social convention but also as an allusion to ancient themes of romance, loyalty, and freedom of the spirit, is still alive today in China and elsewhere. Since time immemorial, wine has played an indispensable role in so many of our human endeavors. This ancient tradition gives wine, wine lore, and wine-related art their continuing interest today. Court decadence, bureaucratic corruption, and encroachment by foreign forces, however, all contributed to the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912. Yet even the violent and turbulent changes experienced by China and the Chinese people could not efface completely the deep-rooted traditions of the culture. We may not find the grand ceremonies of the imperial ancestor cult performed anymore, but the treasured relics of ancient rites are studied and appreciated. The love of wine, not only as a social convention but also as an allusion to ancient themes of romance, loyalty, and freedom of the spirit, is still alive today in China and elsewhere. Since time immemorial, wine has played an indispensable role in so many of our human endeavors. This ancient tradition gives wine, wine lore, and wine-related art their continuing interest today.

|

|

Edith Frankel, together with her husband, Joel Frankel, founded their Asian art gallery, E&J Frankel, Ltd., in 1967. Mrs. Frankel founded the Far Eastern Art department of The New School for Social Research, New York City, in 1970. She teaches, lectures, and writes on the subject of Asian art and, with her son, has recently published Wine and Spirits of the Ancestors (March 2001), which accompanies an exhibition at their gallery that runs from March 22–April 28, 2001.

James Frankel, son of Joel and Edith, is active in his family’s Asian art business. A Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Religion at Columbia University, he has taught courses in history, comparative literature, and religious studies at Columbia and has authored numerous articles.

All photography by Steven Lonsdale Photography.

Selected Bibliography

*The Art of Wine. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco Exhibition Catalog. November 5, 1985.

*Cameron, Nigel. Barbarians and Mandarins. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1970.

*Chang, K.C. Food in Chinese Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977.

*Board of Editors. Catalog of the Special Exhibition of Shang and Chou Dynasty Bronze Wine Vessels. Taipei: National Palace Museum, 1989.

*Ebrey, Patricia B. Chinese Civilization and Society: A Sourcebook. New York: The Free Press, 1981.

Levathes, Louise. When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405–1433. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994.

Liu, Wu-chi, and Irving Yucheng Lo. Sunflower Splendor. New York: Anchor Books, 1975.

Pope, John Alexander. The Freer Chinese Bronzes. Meridan, CT: Smithsonian Publications, 1967.

Rawson, Jessica. The Bella and P.P. Chiu Collection of Ancient Bronzes. Hong Kong: P.P. Chiu Private Publ., 1988.

Riddell, Sheila. Dated Chinese Antiquities 600–1650. London: Faber & Faber, 1979.

Schloss, Ezekiel. Ancient Chinese Ceramics: Han through Tang Dynasties. Stanford: Castle, 1971.

Thompson, Laurence G. Chinese Religion: An Introduction. 4th Edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1988.

Sun, Yifu, et al., eds. The Silk Road on Land and Sea. Trans. Cui Sigan, et al. Beijing: China Pictorial Publishing Co., 1989

Tsang, Gerald, C.C., ed. Warring States Treasures: Cultural Relics of Zhongshan, Hebei Province. Hong Kong: Urban Council of Hong Kong, 1999.

Yang, C.K. Religion in Chinese Society. Prospect Hills, IL: Waveland, 1991.

Zhoug Guo Jiu Wen Kuo (Chinese Wine Culture). Shanghai: People’s Art Publ., 1997.

|

- Scholarship also suggests later dates stretching into the Dawenkou (4300–2400 B.C.) or Longshan (2400–2000 B.C.) culture.

- Please note there is discrepancy in the field regarding dates of the

early dynasties.

|

|

|