|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 1: Punch bowl and goblets, Cristalleries de Baccarat (1764–present), Lunéville, France, ca. 1867. Cased and acid-etched glass. Punch bowl: H. 23”; Goblets: H. 4 3/4”. Gift of the Decorative Arts Council with funds from the 1999 Antiques Show and Sale, 2000. |

Through the major gift of the Modernism Collection from Norwest Bank Minnesota, The Minneapolis Institute of Arts expanded its collection of twentieth-century decorative arts. Among the acquisitions are examples of glass that complement the institute’s existing collection of early modern glass built over the last two decades.1

The collection represents modish taste, from the aesthetic movement to art deco. This period was artistically eclectic, with styles representing an historical interest in classical Greece and the cultures of Japan and the Near East to an appeal for naturalism and functionalism. Artists in both America and Europe produced glass that pushed the boundaries of innovation in design, style, and manufacture. A number of these changing fashions from the early modern era are illustrated through glass selections from The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

The design of this lidded punch bowl and goblets was first presented in glass by Cristalleries de Baccarat (1764–present) at the Paris International Exhibition of 1867, and today only three sets are known. The set was celebrated at the fair for its scenes of Bacchanalian revelry in the neo-Grec style, a classical movement of the late nineteenth century that was heavily influenced by the archaeology of ancient Greece and often expressed in geometric scrollwork. The scenes were executed through the then-innovative technology of acid-etched engraving,

|

|

|

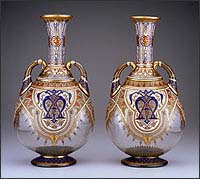

Fig. 2: Pair of flasks, Phillip-Joseph Brocard (active 1867–1896), manufacturer, Paris, France, 1872. Enameled glass. H. 15 9/16”. Purchased through the Decorative Arts Glass Deaccession Fund and Putnam Dana McMillan Fund, 1998. |

whereby acid is applied to an encased body of blue and clear glass and controlled to produce definition and shading of figures, palmettes, and other designs. Decorating through acid reduction was more efficient than labor-intensive copper-wheel engraving, and “the effect is excellent,” according to critic George Wallis of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum) in his 1868 review of the punch bowl and goblets.2

During the aesthetic movement, decorators and manufacturers in America and Europe sought inspiration from a variety of sources, including China, Japan, Persia, and Turkey. Phillip-Joseph Brocard (active 1867–1896) was credited for reproducing glass with enamel decoration that mirrored ancient objects from Egypt, Syria, and the Near East, and his contemporaries referred to his products as “novelties of modern art.”3 Brocard’s command of the popular Islamic style of the late nineteenth century is represented in these two flasks, which are based on actual Islamic enameled mosque lamps. They are also ornamented with the initials of their original owner, “AM,” for the collector, connoisseur, and scholar Alfred Morrison (1821–1897). The lamps decorated Morrison’s London house at Carlton Terrace (now privately owned), the interiors of which remain largely intact and were designed by Owen Jones to complement Morrison’s varied Chinese, Greek, and Persian collections.4 Jones was the perfect choice of designer for Carlton House as he was an authority on the Islamic style, publishing the pioneering text on the subject, Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra (1842).

|

|

|

| Fig. 4: Favrile Floriform Vase, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), designer, New York, ca. 1900. Iridescent blown glass. H. 19”. The Modernism Collection; gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota, 1998. |

Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) was the first modern industrial designer who emphasized function over decoration in machine-produced products of all media, a revolutionary idea before the advent of the Bauhaus and other twentieth-century style movements that supported this approach. In Principles of Design (1872), Dresser stated, “the first aim of the designer of any article must be to render the object that he produces useful.”5 Dresser derived many of his art ideas from Japan, which was officially opened to the West in 1854 and was introduced to the western world through Japanese furnishings exhibited at the London International Exhibition of 1862. The ensuing interest in the exotic Japanese culture and honest workmanship spawned the Japanesque style, art made in Europe and America according to Japanese taste. In 1867 Dresser visited the Japanese Pavilion at the Paris International Exhibition, and in 1877 he spent several months in Japan. The fluidity and geometric shape of this claret jug was inspired by Japanese metalwork and demonstrates Dresser’s attention to the simplicity of form and decoration.

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Claret jug, Christopher Dresser (1834–1904), designer; Heath & Middleton (1887–1909), manufacturer, Birmingham, England, 1892. Glass, silver, and ebonized wood. H. 16 3/4". Gift of the Decorative Arts Council, 1987. |

Similar to Tiffany in America, the Daum Fréres firm (1878–present) in France gained international recognition for its mastery of naturalistic art nouveau designs. Among the wide variety of utilitarian and decorative glass manufactured by the Daum family firm, the best known are its stylized organic forms created by carving cameo or encased glass. At the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, Daum displayed its first products made from the process of acid-etching glass. As seen in this vase, a bitumen-resist was painted on the glass to depict thistle and floral motifs, and then the vase was placed in hydrofluoric acid to reduce unpainted areas. The process was repeated to create the textured layers of the design. Daum’s knowledge and skill in manipulating glass won the firm a grand prize at the Paris International Exhibition in 1900. About the same time, Daum united with the firms of Emile Gallé (glass), Louis Majorelle (furniture), and Victor Prouvé (interior design) to create the Alliance Provinciale des Industries d’Art (later named Ecole de Nancy), which fostered art design and production in Nancy.

|

|

|

| Fig. 5: Vase, Daum Fréres (1878–present), Nancy, France, ca. 1896–1899. Acid carved, etched, and polished glass. H. 20 1/16”. The John R. Van Derlip Fund, 1990. |

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) is the best-known advocate and manufacturer of art glass in America, a market he dominated by the early twentieth century. In 1894, only a year after he opened his glass furnace at Corona, Long Island, Tiffany patented the technique of exposing molten glass to metal oxides and thus creating a brilliantly colorful iridescent surface. Tiffany called this process “favrile” after the Latin word faber (artisan), and it proved successful for creating realistic organic forms such as this art nouveau vase. Here the glass is manipulated in various ways to depict an Egyptian onion with an elongated, plantlike stem and flower. Complementing the rarity of this vase is its fascinating history of ownership by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., who was instrumental in forming the modern design collection at the Museum of Modern Art. The vase illustrates Tiffany’s genius in creating naturalistic designs based on actual flowers, insects, and horticulture, a central premise of the art nouveau movement.

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Wine glass, Otto Prutscher (1880–1949), designer;Adolf Meyer’s Neffe-Adolfshutte bei Winterberg Factory, manufacturer, Vienna, Austria, ca. 1910. Glass with cut decoration. H. 8 3/4”. Miscellaneous purchase funds, 1986. |

After studying with Josef Hoffman (1870–1956) at the Kunstgewerbeschule (Academy of Applied Art, Vienna), Otto Prutscher (1880–1949) worked as a designer for several Austrian manufacturers, including Hoffman’s own Wiener Werkstätte (Viennese workshops). The Wiener Werkstätte were cooperative artisan workshops that in their earliest incarnation produced geometric objects based on creativity and craftsmanship. The workshops had the capability of making objects in different materials, including metals and textiles, but glass was commissioned to other manufacturers, such as Adolf Meyer’s factory. While Prutscher also designed in a variety of media, he is noted for his expressions in glass. In this wine glass, Prutscher used the traditional Austrian or Bohemian glass process of encasing clear glass within a layer of colored glass, which ranged in hue from purple to cobalt blue and was cut or polished to reveal the clear glass. The resulting dramatic checkered motif became a trademark of Prutscher as well as the Wiener Werkstätte.

Lalique is one of the most recognized names in glass production today; the firm’s reputation originated with its namesake and his popular art deco designs of the 1920s. The art deco embraced a variety of sources, including art movements and styles such as the Bauhaus, classicism, and cubism, but in glass it increasingly strove for abstraction and functionalism in design. The term art deco derives from L’Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris (1925), the foremost exhibition of art deco objects, which established the early period of the style as decidedly French and set their standard for luxurious workmanship.

|

|

| Fig. 7: Luminaire, René Lalique (1860–1945), Wingen-sur-Moder, France, ca. 1925. Molded glass. H. 18 1/2”. The Modernism Collection; gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota, 1998. |

A familiar motif in the art deco repertoire is the floral bouquet, and Lalique incorporated a stylized version of it into this lighting device, the luminaire. Designed to create ambience in a dark setting, the luminaire produced a soft, warm glow lit through bulbs placed in the metal base. The glass was formed through metal press-molding, a process invented in America 100 years earlier, whereby molten glass is forced into a metal mold through the weight of a vertical plunger. Similar to other art deco artists, Lalique revived a craft technique but pushed the boundaries of his media and the original methods of production by frosting the glass in acid, contributing to its luminescence.6

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts is highlighting glass this fall through a major exhibition of the contemporary glass sculptor Howard Ben Tré and a survey exhibition of studio glass from the 1950s to the present. Glass is also the theme of the 2001 Decorative Arts Council Antiques Show and Sale in Minneapolis from October 18–21.

All photographs courtesy of The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Jason T. Busch is Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts, Sculpture, and Architecture at The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was previously Assistant Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut.

|

|

- Early modern glass is a component of the museum’s overall glass collection, which spans four continents and 2000 years, presenting an encyclopedic history of the medium.

- George Wallis, “Glass—Domestic and Decorative” in The Illustrated Catalogue of the Paris Universal Exhibition (The Art Journal, 1868), 102.

- Art Journal Catalogue, vol. 10 (1871), 57, as reprinted by Kathryn B. Hiesinger, “Phillippe-Joseph Brocard” in The Second Empire 1852–1870 Art in France under Napoleon III (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1978), 199.

- For more information on Alfred Morrison, see Clive Wainwright, “Alfred Morrison: A Forgotten Patron and Collector” in The Grosvenor House Art & Antiques Fair Handbook (London: The Burlington Magazine, 1995), 27–32.

- Christopher Dresser, “Principles of Design” in The Technical Educator (1872), 277.

- For information on René Lalique, see Patricia Bayer and Mark Waller, The Art of René Lalique (Secaucus, NJ: Wellfleet, 1988).

|

|

|