Biedermeier: The Invention Of Simplicity

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine,

a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

Between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the series of revolutions that erupted in 1848, central and northern Europe enjoyed a period of relative stability and peace. The art associated with this period, and the culture that gave rise to it, have come to be known as “Biedermeier,” a name coined at a later date that sums up both a nostalgia for the period and a criticism of it.1 Although collectors and curators have long been drawn to the art of this period, to date the Biedermeier style and era have eluded clear definition. Biedermeier has variously been identified as a branch of romanticism; a late manifestation both of neoclassicism and romanticism; as an independent self-contained style; and as a prelude to mid-nineteenth century realism. Dates for the Biedermeier period have been equally elusive. Some art historians end the period in 1835 with the death of Austrian Emperor Franz I; others with the outbreak of revolution in 1848.

Biedermeier has its roots in the late eighteenth century. Some early works that date from the turn of that century anticipate the heyday of the purest form of Biedermeier, around 1820. Although the period is considered by some to have lasted as long as thirty-three years, the best examples of the style date from a narrow ten-year span between 1815 and 1825, when new ideas about private life began to circulate throughout central and northern Europe. Simplicity, clarity of line, and geometry of form define the essential building blocks of this aesthetic vision that anticipated modernism.

Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity, currently on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum, elucidates for the first time a clear definition of the aesthetic principles that inform the Biedermeier style around 1820—the moment of the style’s greatest purity—principles that would have a continuing resonance for the European Arts and Crafts movement and the Wiener Werkstätte style at the turn of the century, and even for designers and artists of our own day. This is the first major exhibition in North America to examine the furniture, decorative objects, and fine art from the Biedermeier period (1815–1830).

New research overturns the common assumption that Biedermeier’s spare, simple designs merely reflected bourgeois modesty in taste and the exhausted postwar economies of the period. The rejection of extravagant ornamentation in favor of proportion and utility was largely initiated by the aristocracy and was only later taken up by the newly emerging bourgeoisie. As Hans Ottomeyer, a leading authority on the Biedermeier period, has suggested: “The cult of simplicity developed itself as a principle of beauty in contrast to the luxurious style of the close of the eighteenth century. Whoever could afford to pay for it acquired new decoration in the new style of unpretentiousness.”

New types of cabinet furniture, seating furniture, and tables appeared around 1820, and their rapid evolution toward simplicity of design and form is remarkable. The most elaborate example of these was the writing cabinet, which was both functional and an object of impressive display. Two Vienna writing cabinets (Figs. 1–2) from circa 1810–1815 exemplify the full spectrum of design options available on the furniture market. Both are lyre-shaped luxury pieces crafted with precious woods and veneers. The first writing cabinet (Fig. 1) reflects the lingering influence of the French Empire style in its sculptural decoration and gilding, while the second (Fig.2) relies on the natural persuasive powers of the wood grain and the geometric surface pattern created by the contrasting ebonized banding.

In Biedermeier furniture, veneered surfaces—through sheen, color, construction, and ornamentation—typically express design and shape. Indeed the veneered surface, as Ottomeyer has suggested, is “analogous to a precious, colorful dress with an appealing material structure that is drawn over the body, concealing more than it reveals.”2 A deceptively plain writing cabinet (Fig. 3), attributed to the Munich court cabinetmaking firm of Daniel, demonstrates how a vertically streaked cherry veneer in a symmetrical pattern enhances the architectonic form and scale of the cabinet. The elimination of conventional furniture fittings and the replacement of the usual brass-framed keyholes with diamond-shaped intarsia further contribute to the effect of simplicity.

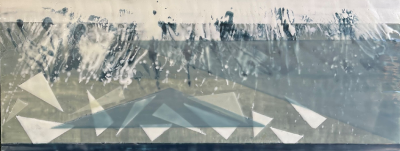

Innovations in seating furniture are perhaps the best-known development of the Biedermeier period, when settees and a veritable tidal wave of new chair designs emerged throughout central and northern Europe. Lighter, portable chairs that could be positioned around a room as needed offered furniture designers the greatest opportunity for individual expression and experimentation (Figs. 4-5). The stark, curvilinear forms of the Bohemian chair from Prague (Fig.5) are the ultimate expression of Biedermeier’s anticipation of Modernism.

A wide variety of chair-backs and upholstery fabrics were made available to satisfy every taste. Improved comfort resulted from technical advances in upholstery, such as the use of metal box springs in the seating surface. Two settees (Figs. 6, 7) demonstrate the same evolution toward simplicity seen in the writing cabinets. The early white silk settee (Fig. 6), based on the design of Josef Danhauser, illustrates the use of draperies, borders, and cords to define the upholstery and to create a surface pattern that alleviates the ponderous character of the piece. Only ten years later, the brilliantly colored orange settee (Fig. 7) with contrasting blue cording is so geometric in design that it is often thought to date from the 1920s or even the 1960s. The upholstery assumes a weight-bearing, tectonic function similar to the use of veneers in cabinetmaking.

Cultural life was centered almost entirely in the home during the Biedermeier period. Furniture innovations reflected a new emphasis on the private household sphere that developed in the postwar period. People often performed a number of activities in a single room, so islands of furniture groupings were employed within the same living space. Restrained, tasteful interior décor and costume emerged to complement well-ordered domestic lives. In genre painting and portraiture, sitters are almost always shown in their own homes or gardens, and their furnishings are lovingly depicted, often reflecting and reinforcing the characters of their proud owners. This concept of the interior is clearly represented in Georg Friedrich Kersting’s interiors populated by his friends and family members (Fig. 8). Kersting and other artists of his time took up the “window picture” popularized by German Romantic painters, notably Kersting’s Dresden friend and colleague Caspar David Friedrich. For Friedrich, the open window functioned as a highly charged symbol conveying a sense of yearning for nature and the external world. For Kersting, it reinforced the primacy and comfort of the interior world and the identification of the sitters with their elegant surroundings.

In Jakob Alt’s depiction of his easel and drawing table in front of an open window with a sunlit view of suburban Alser, a chair, casually pushed aside, serves as a surrogate for the physical presence of the artist (Fig. 9). Here the incidental and the simple pleasures of nature triumph over the mystical aspects extolled in romanticism. Alt and many of his Austrian contemporaries, among them, Thomas Ender, Matthäus Loder, and Eduard Gurk, were commissioned by Archduke Johann of Austria and later by Emperor Ferdinand I to document the Austrian Alps and the local landscape (Fig. 10). With their reportage approach and exquisite color sense, these artists rank among the very best landscape painters of the nineteenth century.

The decorative arts capture the same brilliant hues and sensuous forms so characteristic of Biedermeier furniture and painting. Wallpapers, textiles, porcelain, and even glass all display unexpected exuberance of color and pattern. In some cases, uninterrupted chromatic fields define space and form; in others, contrast performs the same function. Designers achieved an effect of simplicity with vivid wallpapers by treating the wall as a single decorative whole (Fig. 11). According to contemporary theories of perception, the use of complementary colors for upholstery and white or gray for accents and draperies contributed to a healthful, stimulating environment for living. Similar principles of design can be found in the Viennese porcelain writing set (Fig. 12), which relies on a few simple bands of white to enhance the underlying geometric forms and to balance the striking green color.

Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity at the Milwaukee Art Museum runs through January 1, 2007. It will travel to the Albertina in Vienna (February 2 to May 13, 2007), the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin (June 8 to September 2, 2007), and to the Musée du Louvre in Paris (October 15 to January 15, 2008). For information call 414.224.3264, or visit www.mam.org.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

Laurie Winters, curator of European art at the Milwaukee Art Museum, is the co-curator of the exhibition along with Hans Ottomeyer, director of the DHM in Berlin, and Klaus Albrecht Schröder, director of the Albertina in Vienna. Many of the ideas expressed in this article are more fully articulated by Hans Ottomeyer and Christian Witt-Dörring in the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition.

2. Quoted in Hans Ottomeyer, Klaus Albrecht Schröder, and Laurie Winters. Biedermeier: The Invention of Simplicity (Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2006), 83.