Hiawatha in Rome: Edmonia Lewis and Figures from Longfellow

In November 2000, two pieces of nineteenth-century late-neoclassical sculpture, each a bit over one foot in height, sold at a Christie’s auction in New York City. Riding the crest of a decade-long wave of renewed interest in the sculptor, both pieces readily exceeded their $60,000 upper estimates (Figs. 1, 2). The marble busts of Longfellow’s characters Hiawatha and Minnehaha, acquired by winning bids for the Newark Museum, were the work of Edmonia Lewis (ca. 1840–after 1911), whose mother was of African-American and American Indian descent, and her father Haitian.

|

| Left: Fig. 1: Hiawatha. Inscribed and dated Edmonia Lewis Fecit à Roma 1868 and Hiawatha. White marble. H. 14 1/4 in. Courtesy of Newark Museum; photography courtesy of Christie’s. Right: Fig. 2: Minnehaha. Inscribed and dated Edmonia Lewis Fecit à Roma 1868 and Minnehaha. White marble. H. 12 1/4 in. Courtesy of Newark Museum; photography courtesy of Christie’s. |

Lewis is considered to be the first black American to gain an international reputation as a sculptor. Following studies at Oberlin College in Ohio, she arrived in Boston in 1862 with letters of introduction to William Lloyd Garrison and other abolitionists, black and white. Working in the Studio Building at the corner of Bromfield and Tremont streets, Lewis studied with sculptor Edward Brackett (1818–1908). She was soon advertising portrait busts and terra-cotta medallions of champions of the antislavery cause, including Senator Charles Sumner, Maria Weston Chapman, the martyred John Brown, and the black Sergeant William H. Carney (1840–1908), a hero of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment in the 1863 Civil War battle at Fort Wagner.1

The successful sale of copies and photographs of her bust of Robert Gould Shaw (1837–1863), the Brahmin colonel who died at Fort Wagner, along with continual financial help from her older stepbrother, Samuel, who had financed much of her three year stay in Boston, allowed Lewis to travel and study abroad. After visiting England and France, and following a stay of some months in Florence, Italy, she settled in Rome in 1866. Her first studio was on via della Frezza in a building once occupied by the “patron saint” of many of the late neoclassicists, the sculptor Antonio Canova (1757–1822). She spent most of the rest of her life in Rome, taking frequent trips to the United States to exhibit and sell her work.

|

| Fig. 3: Albert Bierstadt (German-American, 1830–1902), Departure of Hiawatha, 1868. Oil on canvas, 67/8 x 81/8 inches. Courtesy of National Park Service, Longfellow National Historic Site. Bierstadt presented Longfellow with this painting in 1868 when the poet was in England to receive an honorary degree at Cambridge University. Today, it may be seen at the Longfellow House, Cambridge, MA, which will reopen to the public following major restoration in the summer of 2002. |

While it was unusual for established sculptors to carve the final marble statue themselves, it was widely reported and commented on that Lewis did all of the work on her early pieces, from clay to plaster to marble. Starting out, she could not afford to hire assistants. Further, she was acutely aware that, as was true for eighteenth- and nineteenth-century African-American writers, a young black woman working in the fine arts risked accusations of fraud from large segments of the public who believed such accomplishments were impossible. An article in Boston’s The Daily Evening Transcript describes Lewis “in her coarse but appropriate attire, her black hair loose, and grasping in her tiny hand the chisel which she does not disdain—perhaps with which she is obliged—to work….”2

| |

| Carte de visite photograph of Edmonia Lewis by H. Rocher, Chicago, IL, ca. 1868. Courtesy of a private collection. The only known photographs of Lewis are seven poses from this same session. Rocher was celebrated for his photographs of well-known personalities in the arts. |

Lewis is perhaps best known today for her emancipation piece, Forever Free (1867), and her recently recovered The Death of Cleopatra (1876), an acclaimed, monumental work exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.3 She enjoyed considerable success in her heyday between the 1860s and the late 1880s, and then, along with most of the late neoclassicists, fell from public favor as the art world turned its focus from Rome to Paris.

As a friend of Anne Whitney, Harriet Hosmer, and Charlotte Cushman, Lewis was a member of the group of expatriate British and American women artists in Rome dubbed by Henry James, in his 1903 biography of William Wetmore Story, “the white marmorean flock.” About Lewis he wrote: “One of the sisterhood…was a negress, whose colour, picturesquely contrasting with that of her plastic material, was the pleading agent of her fame.” James’s sarcasm notwithstanding, Lewis’s work was much in demand. Her studio, listed in the best guidebooks, was a fashionable stop for travelers on the mid-nineteenth-century version of the Grand Tour. Some visitors commissioned portrait busts of themselves or family members. Others ordered her biblical, literary, historical, or idealized classical figures to adorn their mantels and front parlors. She also created copies of a well known antique bust of the Young Octavian, something of a mainstay in Roman studios for tourists in search of the familiar that also spoke for antiquity. At the same time, Lewis did not hesitate to turn out plump, cavorting putti in the guise of Cupid Caught in a Trap (1876) and Cherubs Asleep and Cherubs Awake(1871–1872), multiples of which could be counted on to keep the pot boiling. To date, the checklist of Lewis’s work runs to some eighty pieces of sculpture—marble, plaster, and terra cotta. Not all of her work has been located; just one drawing has come to light.

Lewis’s figures based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s (1807–1882) 1855 poem “The Song of Hiawatha” were particular favorites of collectors, as they were created by the hand of a woman known to be part Indian. Lewis claimed she shared Hiawatha’s Ojibway (often called “Chippewa”) descent and regaled her early patrons with stories of a childhood spent wandering in the wilds with her mother’s people. The stories were more fancy than fact told by the young artist who actually lived her first years in the North Ward of Newark, New Jersey. None of her Indian figures reflects a direct experience or observation of Ojibway life. Instead, responding to the enthusiastic market for such work, she drew upon scenes from “Hiawatha” for a series of groups and busts depicting the fictional Indian brave and his beloved Minnehaha.

The impact of Longfellow’s poem was remarkable when it first appeared, and its influence has, to a lesser degree, lasted for generations. Four thousand volumes of the initial printing of 5,000 were sold by the November 1855 publication date. By mid-December, 11,000 volumes were in print. Longfellow’s publisher, James T. Fields, announced in January that they were selling 300 copies a day, and so it went for years, likely making “Hiawatha” the best-selling American poem of the entire nineteenth century. Within months of the work’s publication, artists of all sorts apparently found it an irresistible source of inspiration. Composers, dancers, actors, painters, sculptors, among others, all found eager audiences for their interpretations of episodes from the epic fantasy.

Albert Bierstadt’s (1830–1902) glowing canvas Departure of Hiawatha was presented to Longfellow at a dinner in his honor in London in the summer of 1868 (Fig. 3). Poet Robert Browning, painter Sir Edwin Landseer, and Prime Minister William Gladstone himself were present for the occasion. For several decades thereafter, many artists turned to the poem that had initially sparked their imaginations in childhood. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s first life-size sculpture was his 1872 depiction of Hiawatha as a pensive youth alone in the forest. Two years later, Thomas Eakins painted the scene of Hiawatha’s victory over the corn god.

| |

| Fig. 5: “Blanche of Burgundy Praying Before Saint Benedict,” Savoy Hours; fragment of the original text. This section attributed to the workshop of Jean Pucelle, ca. 1334–1348. Tempera and gold on parchment, 201 x 147 mm. Courtesy of Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Ms. 390, f. 7. |

Currier & Ives offered seven different prints based on the story, and over several generations, great illustrators from Frederick Remington to N.C. Wyeth kept dramatic scenes from Longfellow’s pen before the eyes of millions of readers. How to explain such an intense and prolonged response to a poem whose rhythms have managed to permanently establish themselves in a corner of the American psyche? To this day, any number of people recognize that singsong incantation, “By the shores of Gitche Gumee, / By the shining Big-Sea-Water,” even if they know little else of what follows.

Longfellow made his Indians both exotic and romantic, though not particularly threatening, removing them from the realm of the violent and politically ruthless government-versus-Indian realities of the day. Bierstadt’s painting, on the other hand, reflects the then-popular thought that the time had come to bid a melodramatic farewell to America’s noble savages. While a few figures in the tale are of a wilder disposition, Hiawatha is readily domesticated by his passion for Minnehaha. As a couple, Hiawatha and Minnehaha were soon so widely known, so distinctly American, that they ranked with George and Martha Washington for sheer recognition as national symbols.

Moreover, Longfellow’s Indians offered a romantic palliative eagerly embraced by the antagonistic factions of a country about to go to war with itself. “The Song of Hiawatha” was published only three years after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book whose sales were often comparable to those of “Hiawatha.” Longfellow was writing at the height of the fury over the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, a period when blacks in the North were at the mercy of bounty hunters and could in no way be mythologized. So while Stowe attempted to provoke moral outrage and political action for African Americans, Longfellow conjured up a tale of prelapsarian primitives. Each writer offered the reading public a supposedly intimate view of two segments of the population who, it was believed, could never be assimilated—views that furthermore spoke to the uncertain future of the nation.

Completed between the years 1866 and 1872, Edmonia Lewis’s depictions of Indians were an immediate success. Newspaper accounts of Lewis’s work in her Roman studio invariably commented on the presence of the familiar icons from the celebrated poem. Americans visiting Rome, it seems, were delighted to encounter figures and scenes from their own beloved “Hiawatha” in the rarefied company of old and new works in the classical tradition. Longfellow’s characters, purveying an idealized New World history, joined centuries of heroic representations in marble, the very medium of age and permanence.

Lewis’s Marriage of Hiawatha (ca. 1866–1868) shows the couple with hands clasped, poised to step forward into their new life together. That first piece was followed two years later by busts of Hiawatha and Minnehaha. Her elaborate group The Old Arrowmaker and His Daughter (1866, 1872), is also called The Wooing of Hiawatha based on passages from Longfellow’s chapter X called “Hiawatha’s Wooing”:

At the doorway of his wigwam

Sat the ancient Arrow-maker,

In the land of the Dacotahs,

Making arrow-heads of jasper…

At his side, in all her beauty,

Sat the lovely Minnehaha…

Plaiting mats of flags and rushes;

Of the past the old man’s thoughts were,

And the maiden’s of the future…

And a bit further along:

With the deer upon his shoulders,

Suddenly from out the woodlands

Hiawatha stood before them…

At the feet of Laughing Water

Hiawatha laid his burden,

Threw the red deer from his shoulders;

And the maiden looked up at him,

Looked up from her mat of rushes,…

Lewis captures the precise moment as father and daughter, startled from their reverie, are presented with the gift of the deer that Hiawatha had slain on his way to ask for Minnehaha’s hand.

| |

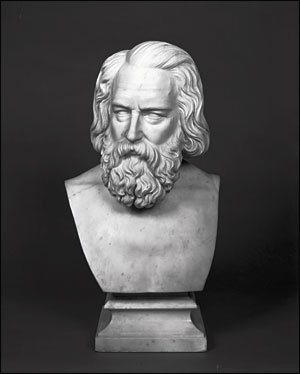

| Fig. 6: Bust of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Rome, 1868–1871. Marble. H. 28.7 in. (73 cm), W. 15.9 in. (40.5 cm). Courtesy of Harvard University Portrait Collection, Acc. No. S052.© President and Fellows of Harvard College. |

In the late 1860s Longfellow visited Rome. Lewis sketched the poet from a discreet distance at receptions held in his honor, as well as from glimpses of him on the street. Longfellow’s brother, Samuel, hearing of the subterfuge, stopped by her studio and was impressed by the bust she was creating from her sketches. Henry himself then visited, pronounced the piece a fine likeness, and sat for the completion of the marble portrait (Fig. 6). Soon after, it was acquired by Harvard College, where Longfellow had taught for many years.

Three marble busts of Hiawatha and four of Minnehaha are in American museums and private collections, as are six of The Old Arrowmaker and His Daughter. Two examples of The Marriage of Hiawatha are in private hands. Other copies of these works, reportedly purchased by European collectors such as Lady Louisa Ashburton, have yet to be located. Longfellow’s reputation, long on the decline, has enjoyed an up-tick with the well-received 2000 publication of a comprehensive edition of his work in the Library of America series. Similarly, as the result of new scholarship and evidenced by impressive sales prices, Edmonia Lewis’s work is increasingly in demand. The poet and the sculptor together have shown us how works of art that so pervasively affected our forebears can strike newly responsive chords as we embrace the twenty-first century.

1. Lewis depicted Carney severely wounded, but holding aloft the company standard. Carney survived the battle and is famous for uttering the rallying cry as he was carried into the field hospital: “The old flag never touched the ground, boys.”

2. The Daily Evening Transcript (14 December 1867).

3. Read more in Stephen May, “The Object at Hand,” Smithsonian Magazine 27 (September 1996): 16, 18, 20.

Selected bibliography:

K. P. Buick, “The Ideal Works of Edmonia Lewis: Invoking and Inverting Autobiography,” American Art (Summer 1995), pp. 5–19.

Linda Roscoe Hartigan, Sharing Traditions: Five Black Artists in Nineteenth-Century America (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), pp. 85–98.

Marilyn Richardson, “Edmonia Lewis’s The Death of Cleopatra: Myth and Identity,” The International Review of African American Art, vol. 12, no. 2 (July 1995), pp. 36–52.

Marilyn Richardson, “Taken From Life: Edward M. Bannister, Edmonia Lewis and the Memorialization of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment,” Hope & Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment (Amherst, MA: The University of Massachusetts Press and the Massachusetts Historical Society, 2001), pp. 94–115.

Charlotte Streifer Rubenstein, American Women Sculptors: A History of Women Working in Three Dimensions (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1990), pp. 51–56.

Marilyn Richardson writes on African-American art and intellectual history. She is the former curator of The Museum of Afro-American History and The African Meeting House on Beacon Hill in Boston, Massachusetts.

This article was originally published in Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|