Frederic Edwin Church in Jamaica

This archive article was published in the Summer 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

“Now for Jamaica . . . the scenery is superb,” Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) remarked when he traveled to Jamaica in May of 1865 in search of new tropical material and respite.1 Church was an established artist, known for his monumental landscapes of New World wonders, when in March 1865, he and his wife, Isabel, lost their two children, three-year-old Herbert and five-month-old Emma, in a diphtheria epidemic. To escape from reminders of their tragedy, Church took his wife to Jamaica, where, during their five month retreat, the Blue Mountains and surrounding verdure provided ample inspiration for the artist (Fig. 1).

At the height of his career, Church had the talent and expertise to make the most of his stay, capturing various weather conditions as well as detailed studies of the flowers, plants, and trees. Friends joined their adventure, including the young landscape painter Horace Wolcott Robbins (1842–1904). Together the two artists travelled to the “Northern side of the island—to a place called Moneague,” where Robbins noted “great trees covered with parasites—vines—and other kinds of trees growing on them.”2 Church depicts the effect of such lush growth in his oil sketch Tropical Vines and Trees, Jamaica (Fig. 2). For Church, the oil sketch was more than a study used only for reference. As Robbins observed in a letter to his sister, “Mr. Church with all his immense natural gifts—has as the result of long years of practice and work—acquired a rapidity which is wonderful to think of and at the same time making his sketches exceedingly elaborate and accurate.”3 After returning home, Church mounted Tropical Vines and Trees, Jamaica on canvas and framed it for delighted visitors.4

Church and Robbins also visited the famous Bog Walk and climbed Monte Diabolo, “a wild and pretty high mountain” that afforded them “the sweetest & finest views” overlooking “the Parish of ‘St Thomas in the Vale’ . . .”5 This prospect “so beautiful and grand” became the inspiration for Church’s grandest Jamaican canvas, The Vale of St. Thomas, Jamaica, 1867 (Fig. 3). The scene looks south over the valley of the Black River with a distinctive tree fern anchoring the foreground. As a token and a testament to the tropical plants he recorded, Church sent a tree fern to his patron, Elizabeth Hart Colt, who had commissioned the painting.

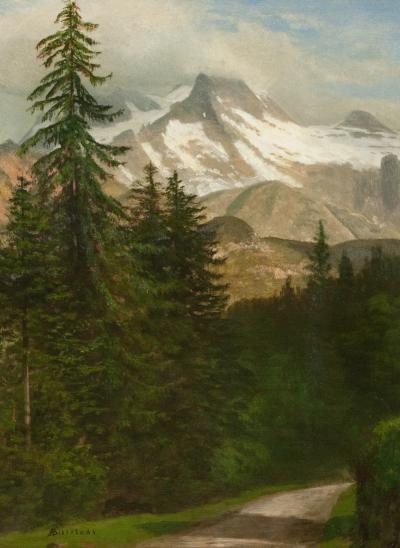

The summer travels of Hudson River School artists provided material for their larger canvases. The artistic goal of Church’s Jamaican excursion was “sketching vines—palms and all that would seem to be useful in our labors of the coming Winters.”6 When Church departed for Jamaica, his Rainy Season in the Tropics (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco), the result of earlier trips to South America, remained unfinished in his Tenth Street studio. Early in his Jamaican stay, part of the island was experiencing a drought, and the contrast between “the gorgeous verdure of the one part and the parched aridity of the other,” provided further material for the incomplete canvas.7 His sketch of the changing weather and cloudy mountain tops (Fig. 4) informed the larger painting.

Church produced many pen and pencil studies, including Coconut Palms (Olana State Historic Site). The drawing, executed on stationery paper, bears the inscription, “Coconuts under sea breeze Kingston Jamaica July 7th 1865.” Three days earlier the Churches and their party had celebrated the United States holiday, in the wake of the Civil War, by hanging an American flag, playing “some National airs,” enjoying “lemon water ice” and setting off a few crackers since “not a rocket could they get — nor any decent fireworks.”8

Nature contributed her own sky displays. In Sunset Jamaica (Fig. 5), Church was also fascinated by the bold rays of the late day sun. Back at home in his New York studio, his sketch of a distinctive sunset became the subject of The After Glow (Fig. 6), where the sun’s rays and the ruined building in the foreground have led scholars to interpret the work as a memorial to Frederic’s younger sister, Charlotte, who died in January 1867. Church’s parents purchased the painting, a sign that the work held special family significance, and after their deaths the work hung in the artist’s own home.

While Frederic explored and sketched, Isabel found her own way to take pleasure in the bounty of the island. In a note to Theodore Cole, Church wrote, “Mrs. Church is fascinated with the occupation of fern collecting and has already an enormous collection—we have them of all sizes from 1/2 inch to 8 feet in length.”9 She collected many of the specimens and artfully arranged them in a herbarium (a book of pressed plants). Isabel presented some of the ferns with a more scientific bent, including their roots, while other pages show three or four different varieties overlapping each other and forming a lovely pattern (Fig. 7).

In Fern Walk, Jamaica (Fig. 8), Church depicts the area he later described to Charles de Wolf Brownell (1822–1909), when Brownell was planning his own Jamaican excursion, “the vegetation, next to that on the Magdalena River, the finest I ever saw—The ferns, especially in the region known as Fern Walk—excelled every place.”10 Another friend and tropical enthusiast, Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), sketched Fern Walk during his trip in 1870. Sharing their experiences Church mused, “What a pleasant thing it would be if a few hours travel would take us at any time to such an island.”11 When in the States, many friends and fellow travelers stayed with the Churches at their Hudson Valley home, Olana (Fig. 9). As part of their 250-acre designed landscape, the Churches planted a fern bed of cultivated specimens native to North America that became a fern walk for Frederic, Isabel, their four children born after the Jamaica trip, and their many visitors (Fig. 10).

The delights of Olana included works by other artists. An oil study of a Pelican Flower (Aristolochia grandiflora) (Fig. 11) was recently attributed to the British flower painter and avid traveler Marianne North (1830–1890). The work may have been a gift to Church during North’s second visit to Olana in 1881, an apt present since the sketch illustrates a vine that she recognized while exploring Jamaica, and which could have been perfect for Frederic and Isabel’s collection.12

Fern Hunting among These Picturesque Mountains: Frederic Edwin Church in Jamaica, is on view in the Evelyn and Maurice Sharp Gallery at Olana from June 6 through October 31, 2010. It features Church’s Jamaican sketches, a selection of his Jamaican photographs, and works by his artist friends who also visited the island. In conjunction with the exhibition, the fern bed and surrounding landscape on the north side of the house is being restored. The exhibition, co-curated by Evelyn D. Trebilcock and Valerie A. Balint, the accompanying book with essays by Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser and Katherine E. Manthorne, and the restoration of the fern bed are funded by The Olana Partnership, the not-for-profit support arm of Olana State Historic Site. Olana, the Churches’ Persian-inspired home, is owned and operated by New York State Office of Parks Recreation and Historic Preservation. For more information call 518.828.0135 or visit www.olana.org.

-----

Evelyn D. Trebilcock is the curator of Olana, Hudson, New York, and the co-author of Glories of the Hudson: Frederic Edwin Church’s Views from Olana (2009).

This article was originally published in the Summer 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized copy of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Horace Wolcott Robbins to his sister Mary Robbins, May 18, 1865. Collection of the late Mary Rintoul.

3. Robbins to his sister, June 30, 1865.

4. Marianne North, Recollections of a Happy Life, Being the Autobiography of Marianne North, Vol. 1, facsimile edition, ed. Susan Morgan, (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1993), 68.

5. Robbins to Mary Robbins, May 18, 1865.

6. Robbins to Mary Robbins, June 30, 1865.

7. Church to Cole, July 28, 1865, OL.1981.863.

8. Robbins to Mary Robbins, June 30, 1865.

9. Church to Cole, July 28, 1865, OL.1981.863.

10. Frederic Church to Charles de Wolf Brownell, November 6, 1893. Copy from an unknown source, Olana Research Collection.

11. Frederic Church to Martin Johnson Heade, January 6, 1871. Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institution.

12. North, Recollections of a Happy Life, 99.