|

|

|

|

by Mary Cheek Mills

|

|

|

|

The Corning Museum of Glass, designed by Gunnar Birkerts. Photography by Carol M. Highsmith.

|

|

|

Nowhere are the mysteries of glass and the skill of its craftsman celebrated more completely than at The Corning Museum of Glass. Long regarded as a destination for scholars and collectors, the museum draws visitors of all ages who want to see and learn about glass and glassmaking.

|

|

|

|

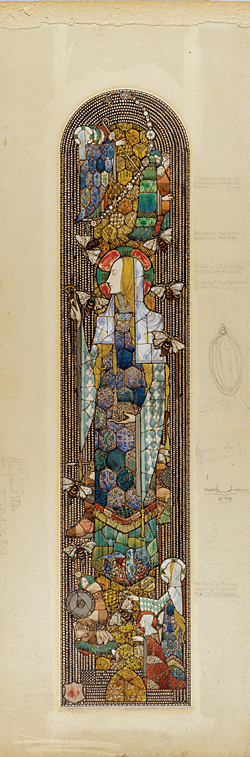

Design for stained glass window depicting St. Gobnet, Harry Clarke, designer (1889-1931), Ireland, 1914. Pencil, pen and ink, and watercolor on board. H. 21.5 in.

|

|

|

|

The Houghton family, who brought the glass industry to Corning in the 1860s and founded Corning Glass Works (now Corning Incorporated), conceived the idea of the museum as a means of marking the family's one hundredth anniversary in the glass business. When it opened its doors to the public in 1951 the museum had a collection of 2,000 glass objects, two staff members, and a research library, all housed in a low, glass-walled building. Although the museum was a nonprofit institution, it was part of the for-profit Corning Glass Center complex, which also included an auditorium for community events, a Hall of Science showcasing the technology of glass, and a windowed wall that permitted visitors to view glass working in the Steuben factory. When the museum opened, then chairman of the board of Corning Glass Works, Amory Houghton, stated it was the purpose of the founders 'to provide in one place the complete picture of a single industry, vital to mankind in all its aspects, historical, aesthetic, scientific, industrial, and sociological.'[1] The museum now houses approximately 45,000 objects, nearly 40 percent of which are on display at any given time, and visitors can explore more than 3,500 years of glass history in the collection galleries.

Having outgrown its original space, architect Gunnar Birkerts designed an addition in 1976 with galleries that, from a bird's-eye view, resemble flames surrounding the glory hole–the mouth of a furnace in which glass is worked. The museum underwent yet another major renovation in 2001, this time designed by architects Smith-Miller and Hawkinson. With each addition, the architects have innovatively revealed the potential and elegance of glass as a building material. Also in 2001 the Leonard S. and Juliette K. Rakow Research Library moved into a separate building on the museum campus. Now the world's foremost library on the art and history of glass and glassmaking, its extensive holdings range in date from a twelfth-century manuscript, Mappae Clavicula, or Little Key to the World of Medieval Techniques (ca. 1150) that presents more than 200 recipes for making various substances used in the decorative arts, to biographies of more recent glass artists. The Studio, The museum's internationally renowned teaching facility created in 1996, offers glassmaking classes to students at all skills levels, while its month long artist-in-residence program allows artists to master glassmaking techniques.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Portrait of an Egyptian king, probably Amenhotep II, Egypt, ca. 1450–1400 BC. Cast. H. 1.6 in. 79.1.4.

|

|

|

Among the museum's early treasures is a small glass sculpture dating from about 1450–1400 BC. It is believed to be a portrait of the eighteenth-Dynasty Egyptian ruler Amenhotep II, identified by his royal headdress and the fact that his ears are not pierced (later pharaohs like King Tutankhamen had pierced ears). Weathered to a tan color by centuries of burial, the sculpture is displayed in front of a mirror showing its original blue glass exposed on the back of the object.

Sometime around 50 BC an ingenious individual realized that if a gather (gob) of hot glass was picked up on the end of a hollow pipe, it could be inflated by blowing through the pipe; gravity would cause the glass to stretch and form a neck and a bottle could be quickly formed. With this technique Roman glassblowers produced glass vessels rapidly and inexpensively, making glass a common commodity. But there is nothing common about the ewer created by inflating a gather into a mold to give the object its form and decoration. Just below the handle a small label in the mold states in Greek, 'Ennion made [it].' We do not know whether Ennion was a designer, a mold maker, a glassblower, or the owner of the glassworks, but he is associated with a small group of objects that bear this mark, making them particularly unusual, since glass work was not typically signed until the mid- to late nineteenth century.

|

|

|

|

|

Ewer signed by Ennion, Rome, mid-first century AD. Blown into a mold, handle applied. H. (including handle and restored foot) 9.4 in. 59.1.76.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cameo plaque, Moorish Bathers, signed George Woodall (1850-1925), Thomas Webb & Sons, Amblecote, England, 1898. Blown, cased, carved and engraved. D. 18.2 in. Bequest of Juliette K. Rakow. From the cameo glass collection of Leonard S. Rakow and Juliette K. Rakow. 92.2.10.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dragon-stem goblet, Venice, Italy, or in the Venetian style, seventeenth century. Blown, pattern-molded, applied, tooled. H. 10.3 in. 51.3.118.

|

|

|

Venetian glassworkers on the island of Murano brought unparalleled virtuosity to the art of glassblowing during the Renaissance. Largely isolated, the artists created glass that imitated precious or semiprecious stones, developed a delicate and almost colorless glass known as cristallo, and perfected a technique known as vetro a filigrana, using twisted white canes of glass. During the seventeenth century, their elaborate dragon-stem goblets, known as vetri a serpenti, were particularly popular. When Venetian glassworkers migrated to other parts of Italy, they helped lend their distinctive style to regional forms and decorative techniques.

In the mid-nineteenth century, glassworkers often looked back to antiquity and the Renaissance for inspiration. In the Stourbridge area of England they began to experiment with the ancient Roman cameo technique that involved layering one color of glass upon another and carving the outer layer(s) to create a design in relief. George Woodall (1850-1925), a glassmaker employed by Thomas Webb and Sons in the town of Amblecote, was a master of the technique of cameo carving. His plaque Moorish Bathers, portraying seven female figures, was his largest and most complex work; it was begun around 1890 and completed in 1898.

From the Gilded Age to World War I cut-lead glass, much of it made in Corning, New York, decorated dining rooms, parlors, and boudoirs in the homes of wealthy Americans. When the Houghtons moved their glass factory from Brooklyn to the rural community of Corning in 1868, glass cutters and engravers had followed them. By 1905 there were 490 glass cutters in the town, which promoted itself as the Crystal City.

|

|

|

|

|

|

L–R: Rouge Flambe vase with iridescent blue decoration, Frederick Carder, Steuben Glass Works, Corning, N.Y., ca. 1916. Blown, tooled. H. 4.9 in. Gift of Tim and Paddy Welles. 2005.4.5.

Window with Hudson River landscape, Tiffany & Co., 1905. Leaded glass. H. 136.3 in. (346.2 cm). 76.4.22.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Evening Dress with Shawl, Karen LaMonte (1967), Zelezny Brod, Czech Republic, 2004. Mold-melted, ground, polished, assembled. H. 59 in. (150 cm). Gift in part of the Ennion Society. 2005.3.21.

|

|

|

In 1903 Thomas G. Hawkes, who owned a cutting firm in Corning, invited a young Englishman named Frederick Carder (1863-1963) to run his new company, Steuben Glass Works. Carder managed the firm until the 1930s and designed thousands of shapes and colors of glass. His decorated Rouge Flambe vase is one of only two such known pieces by him. The opaque red color was extremely difficult to make. Carder's iridescent blue leaves and vines are in striking contrast with the body of the vase, dramatically exhibiting his passion for color.

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), Carder's contemporary, is perhaps the most famous name in American glass history. A large Tiffany stained glass window, presenting a view of the Hudson River framed by hollyhocks, clematis, and trumpet vines and designed for the music room of a Gothic Revival mansion, Rochroane, in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, graces the entrance to the museum's modern gallery. Although called stained glass, the color is not applied; instead, it is in the glass itself. Making glass of many colors and textures, as well as selecting the appropriate piece for each section of a design, was the true genius of Tiffany Studios.

The museum also exhibits an outstanding collection of contemporary sculpture and large-scale installations. Among the hundreds of artists represented are Stanislav Libenskye and Jaroslava Brychtove, Lino Tagliapietra, Dale Chihuly, Howard Ben Tre, and Karen LaMonte, a young American glass artist who works in the Czech Republic, and who uses live models to create her large castings. A major exhibition of contemporary glass, showcasing 230 objects made by eighty seven international artists, formerly in the collection of Ben and Natalie Heineman of Chicago and recently donated to the museum, will open in May 2009.

The collection is only part of the story of glass that is told at the museum. Throughout each day, gaffers (master glassworkers) present narrated demonstrations using tools and techniques very similar to those that have been employed for thousands of years. Visitors can also learn about glass making technique and design by working with trained staff members to create their own pressed and blown glass decorative objects. In its Glass Innovation Center interactive exhibits range from the history of bottle-making machines to optical fiber communication; presenters explain the properties of glass and explore concepts such as tension in glass and color changes with various metallic oxides.

Each year The Corning Museum of Glass introduces thousands of visitors to the world of glass, encouraging them to develop a broader and deeper interest in the medium and to appreciate its infinite possibilities. For more information visit www.cmog.org.

|

|

|

| Mary Cheek Mills is Education Programs Manager at The Corning Museum of Glass. She also teaches glass history and technology for various graduate programs. |

|

|