|

| Home | Articles | Connected to the Past: Objects from the Collections of the Newport Historical Society |

|

|

by Ruth S. Taylor

|

Founded in 1639, Newport was the de facto capital of Rhode Island until after the American Revolution. Unlike its Massachusetts and Connecticut neighbors, colonial Newport was noted for its religious tolerance and was a thriving commercial center that attracted craftsmen and artisans and the citizens with the wherewithal to patronize them. Although British occupation during the Revolutionary War destroyed the city’s maritime economy and caused large numbers of residents to flee, by the mid-nineteenth century Newport had begun to thrive again as a summer colony for the wealthy, a Navy base, an artist’s haven, and, in the twentieth century, known for its music festivals and sporting activities, including polo, lawn tennis, and the America’s Cup competition. Newport contains more surviving colonial structures than any other American city, with many still being used for their original purposes: eighteenth-century buildings are still home to residents and businesses, and three-hundred-year-old taverns still serve customers. The Newport Historical Society owns or maintains five of Newport’s most important colonial structures: The Great Friends Meeting House (1699), the Wanton-Lyman-Hazard House (1696), the Seventh Day Baptist Meeting House (Richard Munday, 1730), the Colony House (Richard Munday, 1740), and Peter Harrison’s Brick Market (1762), which now houses the Museum of Newport History, used as the Society’s visitor center and exhibition space.

Founded in 1853 to preserve Newport’s past, the Historical Society’s need to display its collections led it to acquire its first historic property in 1884: the Baptist Meeting House. This structure is currently being restored to a more historic appearance. The headquarters, which incorporates the Meeting House, is within a brick wing that houses a library with documents dating to the mid-seventeenth century; collections research; fine and decorative arts by Newport’s finest silversmiths, furniture-makers, clockmakers and painters; and objects associated with iconic American figures such as George and Martha Washington, Oliver Hazard Perry (who was born in Newport), and Paul Revere.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

James Nicholson (1848–1893), Newport Harbor, 1888. Oil on wood board, 24 x 30-1/2 inches. Purchased from Hyland Granby Antiques, 2000.40.

|

This luminous scene of Newport harbor is one of less than a dozen known works by this Newport artist. A self-taught artist and an early photographer, Nicholson was born in Scotland in 1848 and came to Newport as a master joiner to work on the interiors of some of the new cottages being built for wealthy summer residents, including Marble House (1892) and the Breakers (1893). The vista gives us an accurate picture of Newport harbor in the late nineteenth century, including factories, wharves, and many Newport church spires. A historically accurate ship, the Eolus, is shown docked on Commercial Wharf to the right of center. This steamship ran between Newport and Wickford, Rhode Island, from 1871 to 1892, taking passengers to the railroad station in Wickford Junction. Nicholson’s granddaughter, Natalie Nicholson, lives in Newport and is a member of the Historical Society.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

F. A. Peckham, (1837–1876), Easton’s Beach, ca. 1870. Watercolor on board, 9 x 7 inches. Private gift. 2004.13.19.

|

Born in Middletown, Rhode Island, Felix Augustus Peckham worked and painted in Newport and Middletown, and completed still lifes, portraits, and landscapes. Peckham had a spinal disorder that confined him to a wheelchair as an adult. He was an important enough figure to have had his death notice in The New York Times, and one contemporary assessment of his work was that it was 'superior to the work of many artists of much wider fame.' This picture beautifully captures summer at Newport’s Easton’s Beach. It contains a wealth of historical details about daily life and Newport architecture. Horse drawn carriages travelled down the long 'Bath Road' from the city to the sea and came right onto the beach to discharge their passengers. A hint of the bathhouses constructed to facilitate the trend of 'bathing' can be seen at the far right and are the precursors to the row of bathhouses on the beach today. Men are roughhousing on the beach without their shirts, but the women enter the sea in full bathing dresses.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spoon, Joseph Gabriel Agard (French), ca. 1730-1750. Sterling silver. L. 12-1/4 in. Acquired from Mrs. May H. Bowen, 1964.3.

|

|

During the American Revolution, the Count de Rochambeau landed at Newport on July 10, 1780, to join General Washington's army. For a year his French troops occupied Newport, which had previously been occupied by the British army.

Their arrival was met with joy and relief by Newporters, who had suffered a great deal under the British occupation, and strong relations were established between French and Rhode Island dignitaries. Rochambeau presented this spoon, taken from his personal camp equipment, to Jabez Bowen, the deputy governor of the state, and his family. The spoon is engraved with Rochambeau's crest. At some point, the family added the inscription: "Rochambeau to Lt. Gov. Jabez Bowen, R.I. 1780." In 1969, the Gorham silver company created a reproduction of the spoon and many were sold. Every year since then the Newport Historical Society receives excited phone calls or letters from people who believe they are holding the original Rochambeau spoon. The original was kept within the Bowen family, and came to the Historical Society in 1964.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Easy Chair, Goddard-Townsend School, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1760–1775. Mahogany; upholstery. Dimensions: H. 45, W. 33 in. Gift of Thomas Hale and family, 2006.17.

|

|

Family history relates that the mahogany used to make this chair was grown on a plantation in Honduras owned by William Ellery (1727–1820), Newport’s signer of the Declaration of Independence. The embroidery on the current upholstery was worked by Ellery’s wife, Abigail Carey Ellery, and the chair was presented to their daughter Almy at the time of her marriage to Mr. William Stedman in 1790. It has descended in the family for 250 years, and whenever reupholstery was needed the original crewel work was carefully cut from the older background and sewn to new cloth. The original ground was a dark green canvas. While preparing for an exhibit on Ellery in 2006, Historical Society staff members found the glasses , which date to Ellery’s lifetime, tucked away in a compartment of a desk (NHS 32.1) owned by Ellery.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jeweled locket containing hair of George and Martha Washington, late 19th or early 20th century. Gold, onyx, human hair, and diamond. H. 1-1/2, W. 1-1/4 in. Gift of Mrs. Thomas G. Brown, 81.4.1.

|

|

|

|

This locket, by the New York jewelry company Starr & Marcus (1864–1877), is engraved around the rim: 'Presented Personally to Oliver Wolcott, March, 1797 / Hair of George & Martha Washington.'

Oliver Wolcott was born in 1726 in Windsor, Connecticut. A graduate of Yale, a lawyer, and a judge, Wolcott became an ardent patriot as the colonies moved toward war with Britain. He served on the Continental Congress, signed the Declaration of Independence for Connecticut, and, as a colonel in the militia, lead Connecticut regiments in battle. After the war he served ten years as lt. governor of Connecticut and one year as governor until his death at 72 in 1797.

In the last year of his life, which was also the final year of George Washington’s presidency, he was presented with samples of hair from both George and Martha Washington. Years after the gift, the reddish and white strands of hair were turned into the ornamentation inside this locket. Washington was revered in his lifetime and Martha distributed samples of his hair to several friends and fans. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow inherited such a sample, and also had it turned into a locket. We are not, however, aware of other samples of Martha’s hair.

The locket was donated to the Historical Society in 1981 by Lily Barrett Knut Brown, a descendent of Wolcott’s via the Gibbs family of Newport. A note associated with the locket stated that the stone on the cover was a diamond, though over the following decades the stone was judged unlikely to be real. The firm of Starr & Marcus, however, was famous at the time for its diamond jewelry. Recent testing by Newport Antiques Show participant Dan MacDonald of Three Golden Apples in Newport has revealed that, in fact, set within the locket is a rose-cut three carat diamond.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Teapot, Paul Revere, Jr. (1734–1818), ca. 1765. Silver. H. 5-1/2, W. 9-1/2 in. Estate of Frances Raymond. 98.2.1.

|

Paul Revere is known not only for his midnight ride to announce the attack by the British but also as one of early America’s most important craftsmen. Trained by his father as a silver and goldsmith, his work was highly regarded during his lifetime; the rococo style of this teapot dates it to before the American Revolution. A 1998 gift of Frances Raymond, the teapot descended in the Clarke family of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Newport businessmen and bankers. The gift of documents, artifacts, and costumes, was so large and so valuable that it took several years to catalogue the items. A staff member discovered this beautiful silver teaport marked 'Revere' in a box that contained the final few objects.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

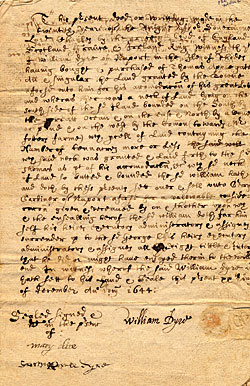

ABOVE: Howard Pyle (1853–1911), Mary Dyer Being Led to The Scaffold, ca. 1905.Oil on canvas, 30-1/2 x 21-1/2 inches. Gift of George L. and Virginia Dyer, 90.1.

Shown here with William and Mary Dyer land deed (RIGHT), Newport, 1644. A126 F5.

|

|

Mary Dyer and her husband, William, were among Newport’s founding families. Born in England, the Dyers became interested in ideas of religious freedom and liberty of conscience. They emigrated first to Boston, and not finding the tolerance they sought there, came with Anne Hutchinson and her followers to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and from there, went south to help found Newport in 1639. This land deed, executed in 1644, was signed by both members of the intrepid couple. After Mary became a Quaker in the 1650s, she began to travel and preach. Although Rhode Island was tolerant of Quakerism and the other new religions, elsewhere was not. In Massachusetts, she was arrested several times for preaching and sentenced to death for the crime of being a Quaker and reprieved, provided she did not return. In spite of the appeals of her family, she was determined to protest the anti-Quaker laws and so returned to Boston. There she was again sentenced and was hanged to death in May of 1660.

|

|

|

|

Howard Pyle, noted American illustrator, painted the execution of Mary Dyer in 1905. The painting came to the Historical Society from William and Mary’s descendant, George L. Dyer.

1. In July 1781, Rochambeau’s force left Rhode Island, joining Washington’s army in a march to the successful siege of Yorktown, now commemorated by the W3R project (Washington Rochambeau Revolutionary Route).

|

|

|

The objects illustrated in this article will be on display at the Newport Antiques Show, being held at St. George’s School in Middletown, Rhode Island, August 8–10, 2008. The show benefits the Historical Society and the Boys and Girls Clubs of Newport County. For information on attending, visit www.newportantiquesshow.com or call 401.846.2669. For more information on the Society, Museum of Newport History, and affiliated historic houses, visit www.newporthistorical.org or call 401.846.0813.

|

|

|

| Ruth S. Taylor is executive director of the Newport Historical Society, Newport, Rhode Island. |

|

|

|