Georgia O'Keeffe and the Camera the Art of Identity by Susan Danly

|

By Susan Danly

From her debut as a provocative young artist in Alfred Stieglitz's photographs to depictions of her as a grande dame of the art world in prints by Andy Warhol, Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986) captivated the media with a persona as bold as her art. As the protege of Stieglitz, one of the early proponents of modern art in New York (and later his wife), O'Keeffe posed in front of her abstract artwork as a manifestation of the sexually liberated woman. Later, through her affiliations with photographers such as Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, and Todd Webb, she redefined herself as a rugged individualist whose identity was linked with the animal bones and barren hills of the Southwest that became her home and a source of her art. After Stieglitz's death in 1946, O'Keeffe moved there permanently.

Georgia O'Keeffe is best known for her paintings of large-scale flowers, New York cityscapes, animal bones, and the landscape of New Mexico. Her extraordinary career focused first on a highly innovative exploration of abstraction and shifted towards powerful representation and heightened realism after the mid-1920s. Photography played an essential role in establishing her reputation, promoting her career, and creating her public persona. O'Keeffe's lasting fame rests on the strength of her work and the romantic story of her life. Photographs made by her art dealer-husband, her friends, celebrity portraitists, and photojournalists all serve to tell various versions of that tale.

This summer the Portland Museum of Art in Maine presents Georgia O'Keeffe and the Camera: The Art of Identity, an exhibition that includes eighteen of O'Keeffe's key works alongside some sixty photographs that highlight her personal and professional relationships with the leading photographers of her day. This is the first exhibition in which paintings and photographs have been paired to establish two opposing public images of the artist. A selection of photographs and paintings appearing in the show are presented here.

|

|

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), Georgia O'Keeffe in Chemise, 1918. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation.

When Georgia O'Keeffe first showed her work in New York in 1916 at Alfred Stieglitz's avant-garde 291 gallery, she was virtually unknown as an artist. By the time of her death, some seventy years later, she was among the most famous people in America. From the beginning, O'Keeffe's professional and personal life were inexorably entwined with the needs and desires of Stieglitz who, over the course of almost thirty years, was her artistic mentor, commercial dealer, portraitist, lover, and, later, husband. Among Stieglitz's best-known works are his portraits of O'Keeffe taken between 1917 and 1933, especially those that showed her nude or posed partially dressed in a robe or chemise in front of her artwork. Such images were quickly linked by the critics to an interpretation of her abstract art as filled with sexual innuendo. Enrapt in her love affair with the much older and professionally influential art dealer, O'Keeffe was in no position to discourage his making and exhibiting nude portraits of her.

|

|

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), Georgia O'Keeffe-Hands, circa 1919. Gelatin silver print, 9-7/16 x 7-1/2 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation.

Stieglitz's portrait series of O'Keeffe eventually included more than 350 images. Among the best known are his close-up studies of her hands. In this one, he has posed the artist in front of one of her early abstract drawings, which he treats as if it had real three-dimensional properties. His image recalls the ancient Greek story of the origins of trompe l'oeil painting. During a contest between two famous artists to produce the most realistic painting, the first depicted a still life of grapes that was so real birds tried to peck at the fruit. The second artist painted a curtain that was even more convincing. It fooled his rival, who attempted to pull the drapery aside to see what lay behind. Stieglitz's photograph of O'Keeffe's hands attempting to grasp what appears to be a three-dimensional object from a two-dimensional drawing underscores the essential conceit of trompe l'oeil illusionism.

|

|

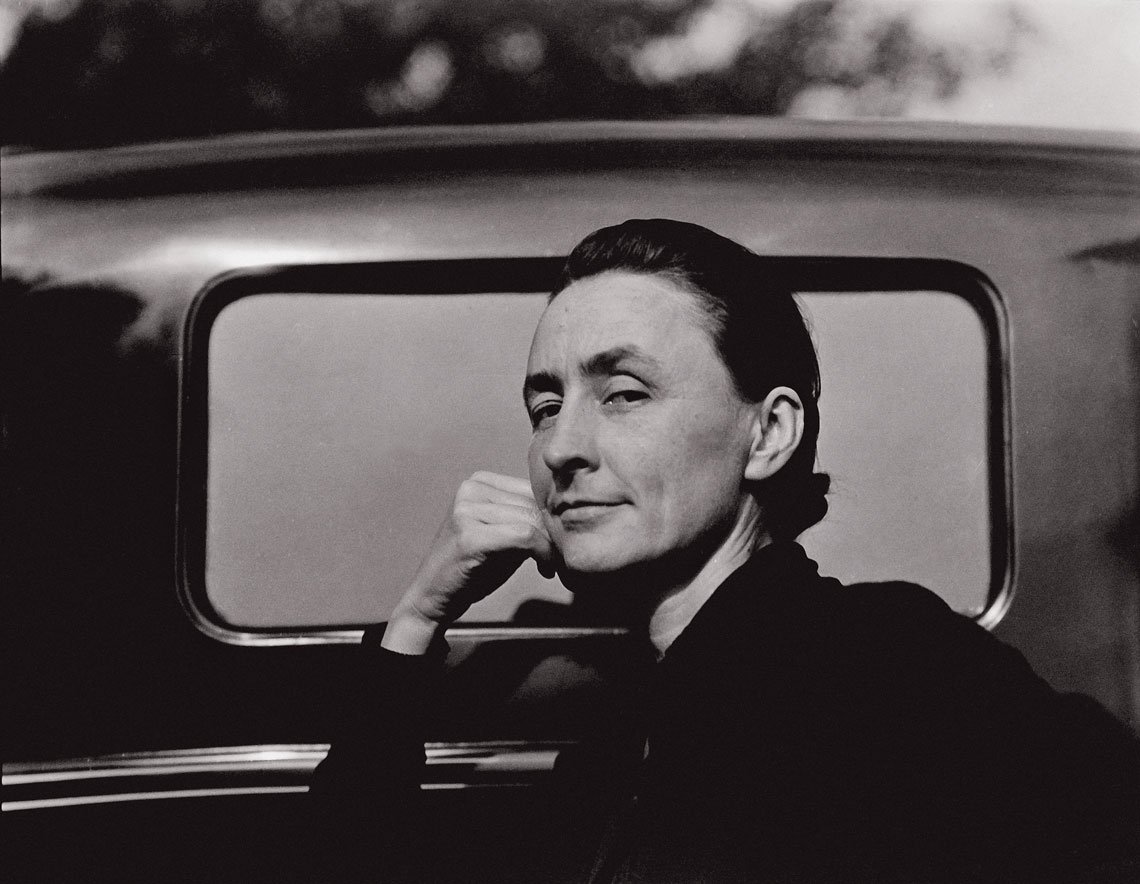

Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946), Georgia O'Keeffe - After Return from New Mexico, 1929. Gelatin silver print, 3-1/16 x 4-5/8 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation.

In 1929, seeking a break from the intensity of her marriage to Stieglitz and a new source of inspiration for her work, O'Keeffe traveled to Santa Fe with her friend Rebecca Strand, the wife of photographer Paul Strand. After their arrival, the two women were taken to Taos, at the insistence of Mabel Dodge Luhan, who welcomed them to her home, Los Gallos, and provided them with a studio. During their three-month visit, they explored the neighboring Indian pueblos, went on sketching and camping trips, and sunbathed in the nude. O'Keeffe purchased a Model A Ford, and they both learned to drive. According to Rebecca Strand, O'Keeffe was a timid driver but loved the car, nicknaming it 'Hello.' In a letter to her husband, Strand captured the sense of fun and relaxation that the trip presented to them: 'This afternoon, G. and I put on our bathing suits, connected the hose, and washed the Ford. Much shrieking with laughter and it came out shining like a new button.' Stieglitz's portrait of O'Keeffe, taken shortly after her return to New York, captures O'Keeffe's newfound sense of independence, related in part to her ability to drive a car.

|

|

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986), Corn, No. 2, 1924. Oil on canvas, 27-1/4 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation.

Because her early abstractions were open to Freudian interpretations, in the 1920s O'Keeffe gradually began to paint more recognizable subjects, including flower subjects and urban views, in hopes of deflecting the discussions of her private life. But the critics continued to see sexual references in works such as this.

|

|

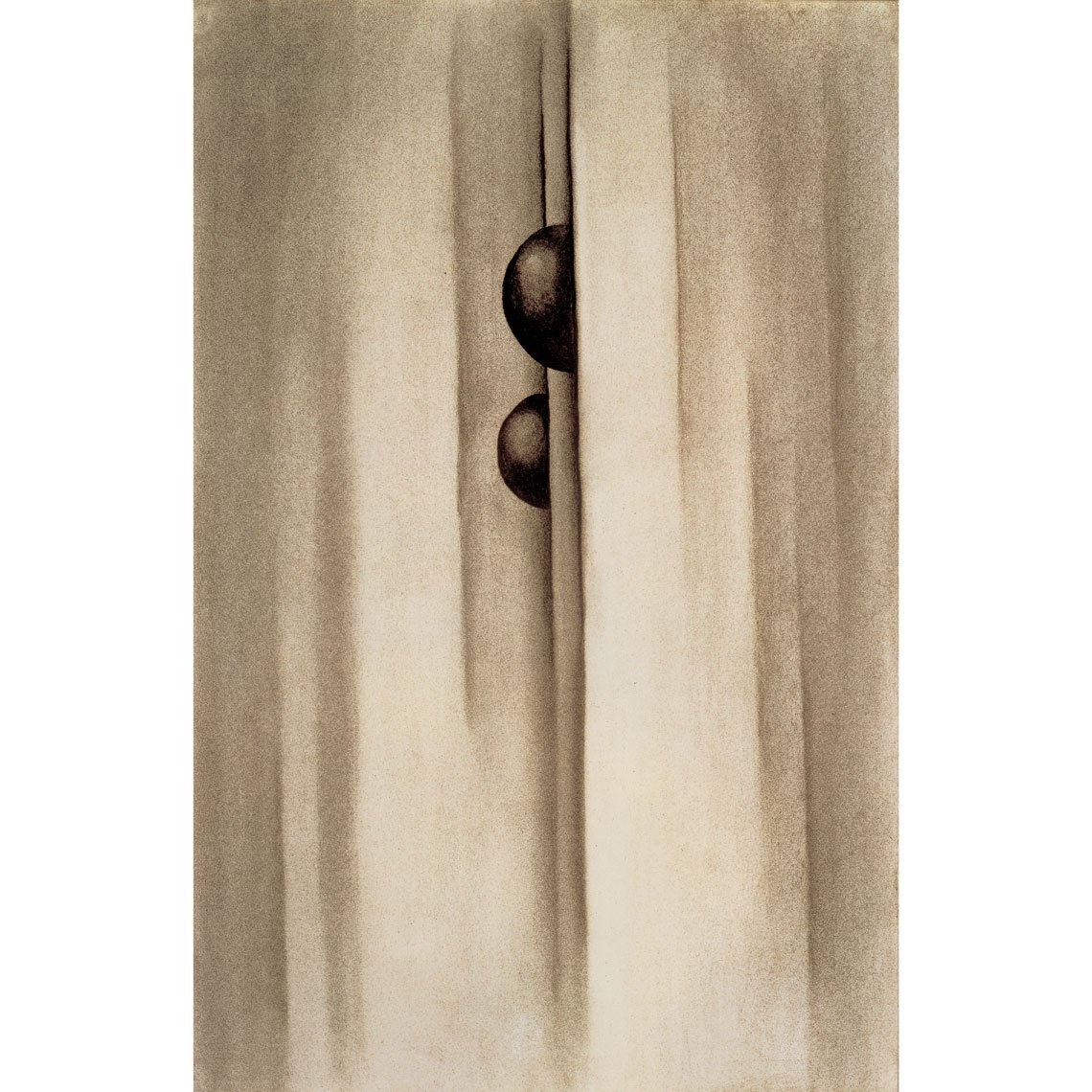

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986), No. 17 - Special, 1919. Charcoal on laid paper, 19-3/4 x 12-3/4 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; gift of The Burnett Foundation and The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation.

This large charcoal drawing, which appeared in the background of one of Stieglitz's famous portraits of O'Keeffe's hands, is typical of the early work that she exhibited at his 291 gallery. Some of these drawings were independent works, and others, such as this one, were made as studies for finished paintings. This drawing served as the source for an abstraction, Green Lines and Pink, 1919 (Georgia O'Keeffe Museum), which is also in the exhibition.

|

|

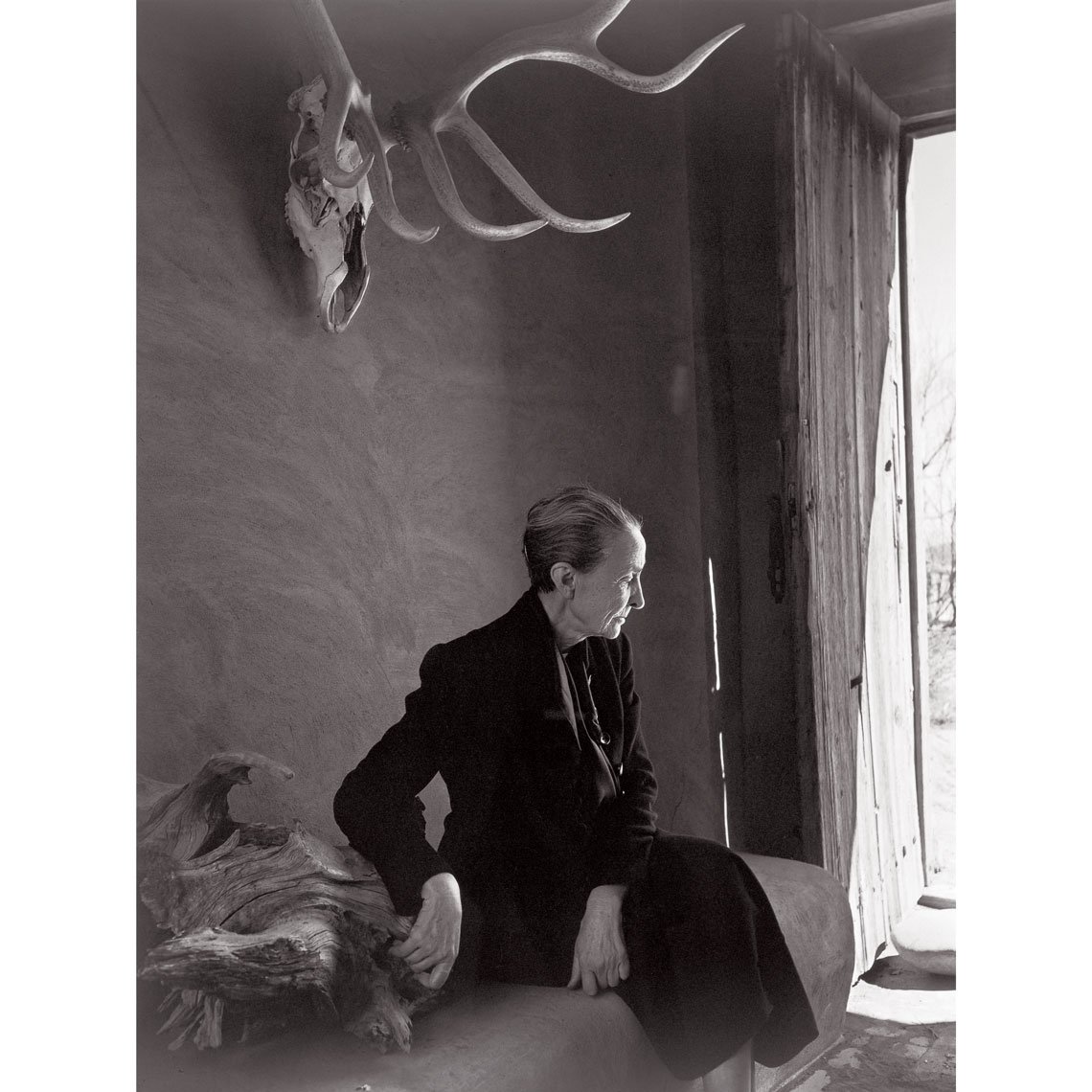

Yousuf Karsh (1908-2002), Georgia O'Keeffe, 1956. Gelatin silver print, 39 x 29-1/2 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe.

In 1945 O'Keeffe purchased a ruined hacienda in the small village of Abiquiu, not far from Ghost Ranch, her studio fifty miles northwest of Santa Fe. She set about restoring the buildings and in 1949 moved to New Mexico permanently. When Yousuf Karsh traveled to Abiquiu to photograph O'Keeffe in 1956, he produced an image that suggested her self-assurance and reflected her artistic concerns. Seated in profile in the entryway of her house, O'Keeffe posed under the large set of antlers that appeared in many of her paintings. Karsh wrote that he 'expected to find some of the poetic intensity of her paintings reflected in her personality. Intensity I found, but it was the austere intensity of dedication to her work, which has led Miss O'Keeffe to cut out of her life anything that interferes with her ability to express herself in paint.' As Stieglitz had done in his portraits of the young O'Keeffe, Karsh drew attention to the artist's hands. For this image of the sixty-nine-year-old artist, he posed her bent fingers next to a gnarled tree stump and placed her under a deer's antlered skull, alluding to the passage of time and death. As if to balance those dark elements, however, a streak of light coming in from the open doorway falls on O'Keeffe's forehead, wrist, and still-life objects in the composition, serving as a reminder of the inspiration and vitality of the still-practicing artist.

|

|

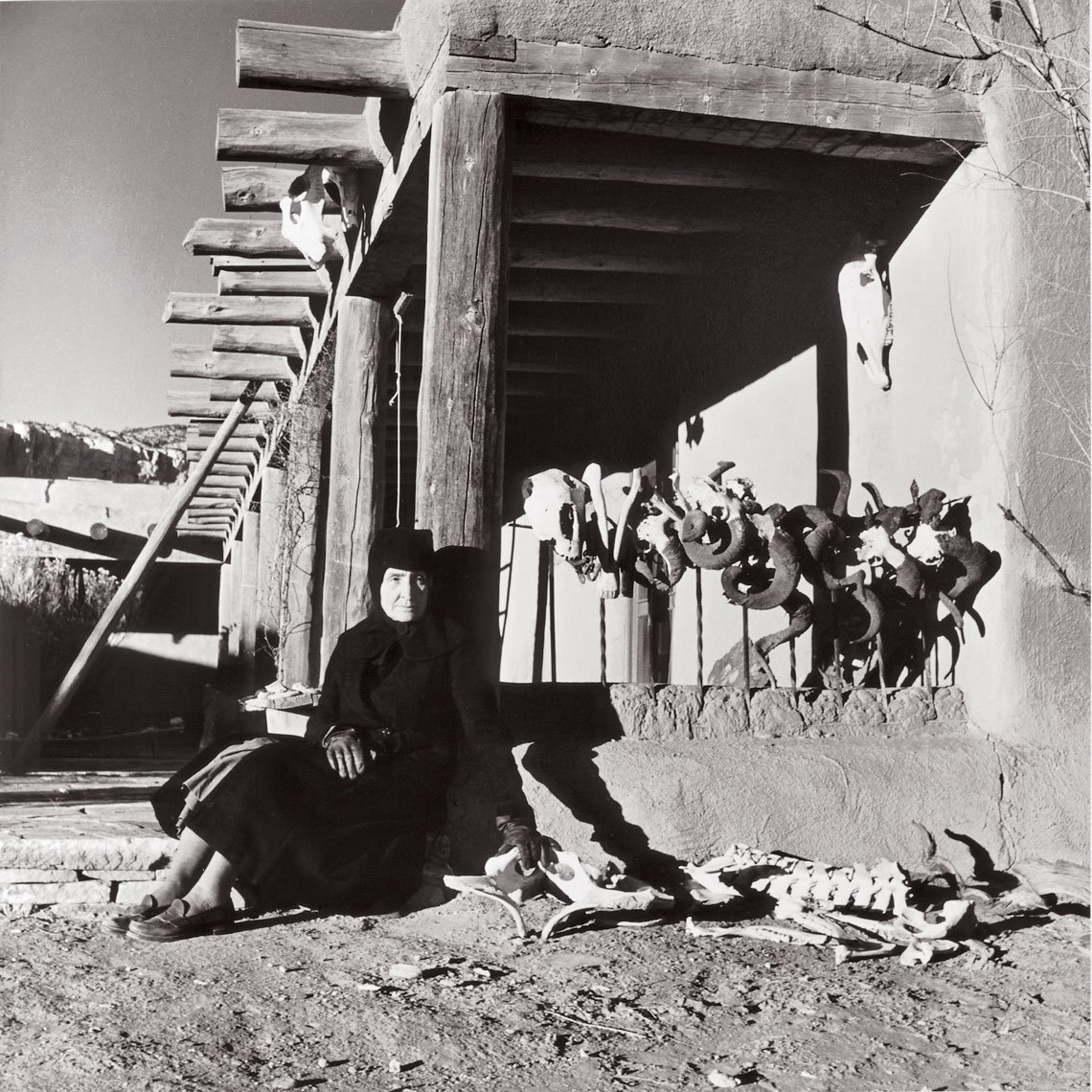

George Daniell (1911-2002), Georgia O'Keeffe Seated Among Her Props, 1952. Gelatin silver print, 10-1/2 x 10-1/2 inches. Courtesy of the Portland Museum of Art; Museum purchase with support from the Barbara Goodbody Photography Fund.

As O'Keeffe's paintings of the desert landscape and dried bones became increasingly appreciated, she invited celebrity photographers like George Daniell to visit Ghost Ranch. Like many photographers, Daniell first met O'Keeffe at Alfred Stieglitz's New York gallery An American Place, one of the two galleries Stieglitz opened in the 1920s after closing 291. Daniell soon became enthralled with her Southwestern persona, and made the pilgrimage to New Mexico to photograph her seated among the many bones she collected during her daily walks and painting forays in the desert. He also recorded her characteristically stark clothing and headgear. She frequently wore either black or white outfits and scarves, which presented her form in sharp contrast to her surroundings in the many black-and-white images of her that appeared in popular magazines of the day, Life, Vanity Fair, and Vogue.

|

|

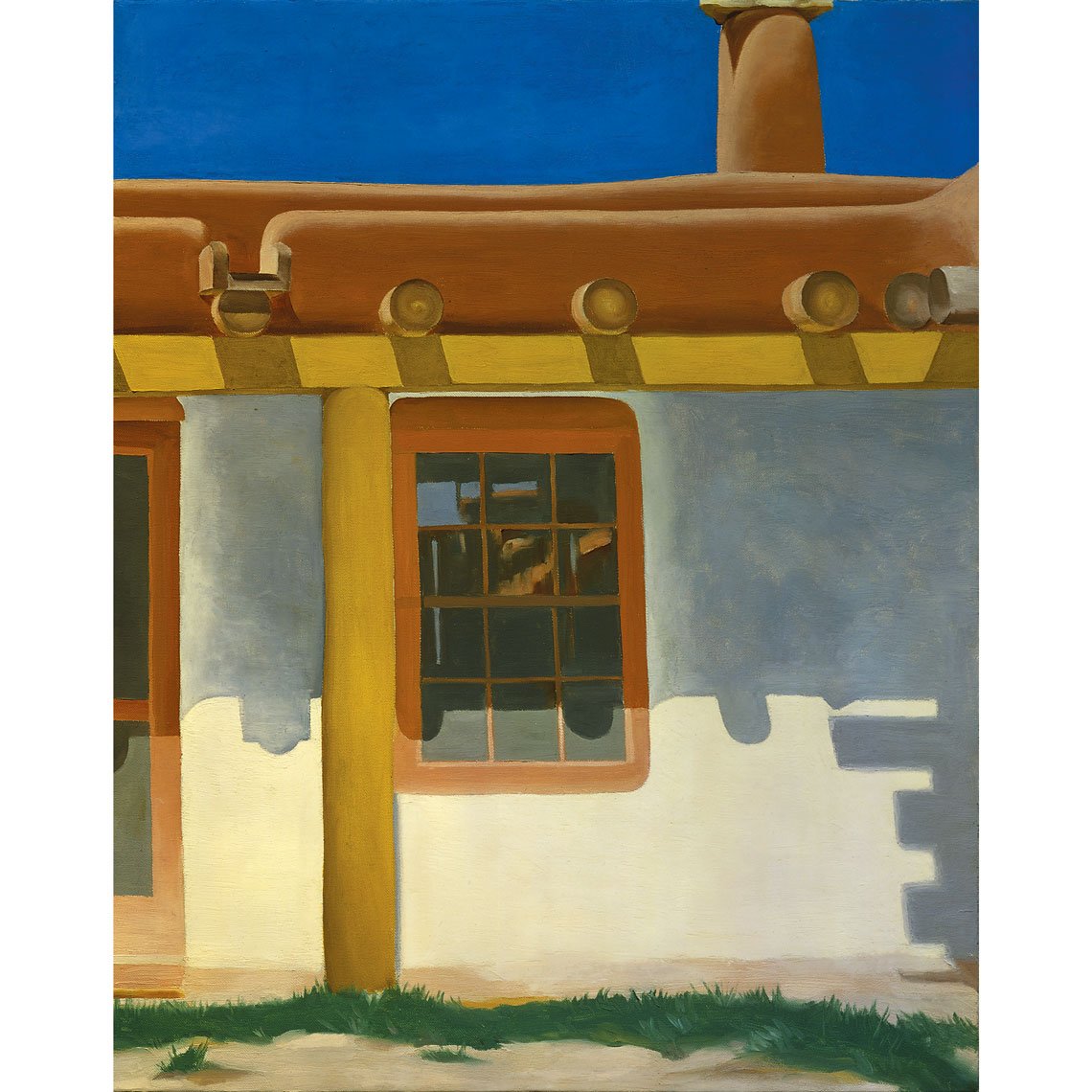

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986), The Patio - No. 1, 1940. Oil on canvas, 24-1/2 x 18-1/2 inches. Courtesy of a private collection, San Francisco, Ca.

As O'Keeffe's paintings of the desert landscape and dried bones became increasingly appreciated, she invited celebrity photographers like George Daniell to visit Ghost Ranch. Like many photographers, Daniell first met O'Keeffe at Alfred Stieglitz's New York gallery An American Place, one of the two galleries Stieglitz opened in the 1920s after closing 291. Daniell soon became enthralled with her Southwestern persona, and made the pilgrimage to New Mexico to photograph her seated among the many bones she collected during her daily walks and painting forays in the desert. He also recorded her characteristically stark clothing and headgear. She frequently wore either black or white outfits and scarves, which presented her form in sharp contrast to her surroundings in the many black-and-white images of her that appeared in popular magazines of the day, Life, Vanity Fair, and Vogue.

|

|

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986), From the River - Pale, 1959. Oil on canvas, 41-1/2 x 31-3/8 inches. Courtesy of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe; gift of The Georgia O'Keeffe Foundation.

O'Keeffe's late career is marked by the return of a greater degree of abstraction, especially evident in this work. Although it depicts a barren tree branch, the pink and ochre hues that dominate move the picture away from mere transcription. After Stieglitz's death, in 1946, O'Keeffe began to travel abroad with some frequency, and her experience of air travel provided a new perspective on the world. Her series of cloud paintings, one of which is also included in the exhibition, convey this new vantage point that informs the ambiguous nature of space in her late work.

|

|

Todd Webb (1905-2000), Georgia O'Keeffe's Studio, the Abiquiu House, New Mexico, 1977. Gelatin silver print. 6-1/2 x 8-3/8 inches. Courtesy of Evans Gallery, Portland, Me.

Late in life, O'Keeffe welcomed the attention of several photographers, including Todd Webb, John Loengard, and Myron Wood, who published extensive photographic essays about her life at Ghost Ranch and at Abiquiu. She was interested in showing her work in the simple setting of her own distinctive interiors, which combined traditional adobe architecture and modern furniture. Several of Webb's architectural images of O'Keeffe's patio, taken in the 1970s at Abiquiu, echo the simple geometry and abstract patterns that also appear in her paintings from the 1950s. He also photographed the interior of her studios at Ghost Ranch and at Abiquiu, with paintings and props hanging on the wall. In one image, Webb positioned an O'Keeffe painting, From the River - Pale, next to the barren tree branch that had served as its inspiration. Without the photograph, the viewer might easily assume that the painting is an aerial landscape view of the nearby Chama River.

|

Georgia O'Keeffe and the Camera: The Art of Identity will run from June 12 through September 7, 2008, at the Portland Museum of Art, Maine. The exhibition will travel to the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where it can be seen from September 26 until February 1, 2009. A companion book of the same title is published by Yale University Press. This exhibition is made possible by the generosity of Scott and Isabelle Black. Corporate sponsorship is provided by Bank of America, with additional support from The Bear Bookshop, Marlboro, Vermont. Media support is provided by WCSH 6 and the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

Susan Danly is curator of graphics, photography, and contemporary art at the Portland Museum of Art, Maine, and one of the co-organizers of Georgia O'Keeffe and the Camera: The Art of Identity.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2009 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|