|

|

|

by Gladys Montgomery with photography by J. David Bohl

|

|

|

|

|

|

A grand view of the residence, which is a union of five historic buildings.

|

In most discussions about collections of antiques, the objects are the focus of attention. But in this instance, the collection includes the structures that house it as well. The five historic buildings that comprise this home were moved to the site in the 1970s and configured by the previous owner. They are: a rare and important mid-seventeenth-century ironmonger's house, a converted early timber-frame barn, an elegant Federal dwelling, and a 1750 house and adjoining ell moved from Northford, Connecticut, and originally owned by the Reverend Warham Williams, the first pastor of the town's Congregational Church and secretary of Yale College.

The structures are linked by a modern entry hall crafted with historic interior details to create seamless transitions between new and old. "The buildings are beautifully married together," notes the current lady of the house. "I can't believe how well it was done." Tucked into the verdant Connecticut landscape, the home she shares with her husband showcases a fine collection of American, English, and continental furnishings, decorative arts, and art, dating principally from the mid-seventeenth to the late-eighteenth centuries.

|

|

|

|

LEFT: The principal entry of the center-chimney Warham Williams house retains its original door surround characteristic of the finer mid-eighteenth-century homes in the Connecticut River Valley, with broken scroll pediment, carved rosettes, fluted pilasters, and heavily molded elements. Only thirteen of twenty-three surviving scroll-pedimented doorways survive on their original houses; this is one of them. The doors have been replaced; the original doors had rectangular raised panels. The door surround and house are recorded in the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) in the Library of Congress (www.memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer) and in Amelia F. Miller, Connecticut River Valley Doorways (Boston: Boston University for the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, 1983). Contemporary plans for recreating the house are also available on www.reproductionhouseplans.com. RIGHT: The Federal-era house is oriented away from the other houses to which it is attached.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Constructed in the shape of an uneven H surrounding a courtyard, the house comprises a 1750 Georgian manse and ell (at left), a steep-roofed mid-1600s ironmonger's house (center), an antique barn with front lean-to (to its right), a modern entry (right), and a Federal-era house (not shown, far right). All period structures were moved from locations in Connecticut, except the ironmonger's house, which originated in Massachusetts.

|

Native Midwesterners who attended Connecticut colleges, the current owners had originally purchased a newer Connecticut country house, which they had revamped with period furnishings and details, including antique paneling acquired from antiques dealer Harold Cole of Woodbury, Connecticut. "We wanted a place to celebrate Thanksgiving and Christmas. We weren't planning on living in Connecticut, but, the more time we spent here, the less we wanted to leave," the wife notes. The area's landscape and historic houses," she says, "stole my heart. I didn't realize how much this was really me."

Though not in the market for a larger country property, the couple was smitten when they saw their current residence. Upon purchasing it some seven years ago, they upgraded its heating and cooling systems, re-did the lighting, updated bathrooms, renovated the kitchen with a period look, and had 13,000 square feet of existing antique wood floors hand stripped of the high gloss lacquer put on by the previous owner.

|

|

|

The entry hall, of modern construction, was crafted with interior architectural details copied from the adjacent music room. The hall links the period buildings and provides a formal entry space. Furnishings include a large Delft bowl atop a massive English gate-leg table with intricate ball-and-ring turnings. Delft vases and covered jars also decorate an English sideboard (left) and a Massachusetts reverse serpentine chest of drawers (right). The high chest of drawers, from Wayne Pratt, Inc., is attributed to Charlestown, Massachusetts, cabinetmaker Benjamin Frothingham (1734-1809) and is a virtual mate to a signed example in Winterthur Museum. The reds of the rug complement the wood tones of the furniture and are echoed in the slip cover on the Chippendale back stool (left) and on the Queen Anne easy chair and Georgian arm chair (right). In the music room beyond, a pair of Chippendale lolling chairs flank a Queen Anne drop-leaf table. Two girandole mirrors are placed on opposite sides of the doorway.

|

|

|

|

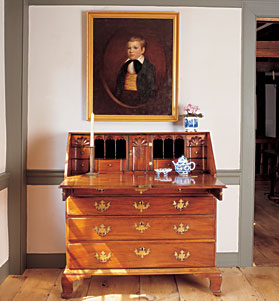

LEFT: This superb slant-front desk, circa 1750-1770, attributed to the Goddard and Townsend school of Newport, Rhode Island, was purchased from Wayne Pratt, Inc. The attribution is based on the blocked interior arrangement, demi-dome valance drawers, carved fans, and the curvaceous bracket feet. The delicate trailing vine of the central prospect door is present on three other Newport case pieces, all of which feature identical interiors and foot profiles. The mid-nineteenth-century folk portrait above is of an unidentified child; the artist is unknown. RIGHT: A lean-to in front of the timber-frame barn fittingly houses a rustic drop-leaf trestle table and banister back chairs. With its dark finish and sculptural turned legs, an early Massachusetts William and Mary high chest stands out against the white walls; the kitchen is visible beyond. A nineteenth-century folk portrait of a woman hangs above the high chest. To the right is a still life painted by the lady of the house. Hanging on the stairway is an oil painting of poultry by Dutch artist Pieter Casteels (1684-1749), who was born in Antwerp and immigrated to England in 1708. Known for his ornithological and floral studies, Casteels collaborated with English engraver Henry Fletcher and nurseryman Robert Furber to produce a set of hand-colored engravings, The Twelve Months of Flowers, the first horticultural catalogue of its time. He died in Richmond, England.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

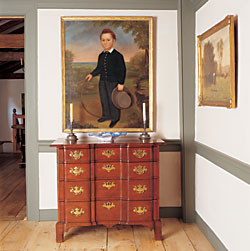

This block-front chest of drawers, from Wayne Pratt, Inc., has tremendous presence with its tall, narrow proportions, balanced overhang, and shaped central drop. Made in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the chest is branded on the back with the name of an early owner, "I. SALTER," most likely the Portsmouth merchant John Salter (1740-1814). The chest was then purchased by a member of the prominent local Wendell family, through which it descended. The chest is illustrated in Jobe, et al., Portsmouth Furniture (SPNEA, 1993), no. 7. The nineteenth-century folk portrait is of an unknown young boy.

|

The interiors and furnishings were completed within twelve months. Much of this was accomplished with the help of California designer and preservationist John Cottrell, who had assisted the couple with previous residences. A visual artist herself, the lady of the house describes Cottrell as "a classic designer, one of the last true classic artists, who doesn't follow trends." She adds, "We would go through the antiques and art magazines, see the ads and go shopping. We'd get together with John, pile into the car and laugh all day. We would cover Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, New York, and Pennsylvania looking for antiques; it was a whirlwind." The dealers with whom they worked included Connecticut Americana dealers Peter and Jeffrey Tillou of Litchfield, the late Wayne Pratt and Harold Cole of Woodbury, and Buckley and Buckley of Salisbury. Massachusetts dealers included Samuel Herrup of Sheffield, Grace and Elliott Snyder of South Egremont, and Peter Eaton of Newbury. They also frequented H. L. Chalfant's shop in Pennsylvania. "A day without buying is a day without trying," the husband joked at the time.

A businessman who appreciates art and antiques for their investment potential as well as their aesthetic value, the husband's taste runs toward the European fine art and Hudson River School paintings that they collected for their first Connecticut house. Recognizing that their present environment calls for more emphasis on collections from New England, the European pieces are now mingled with objects more closely tied to the northern regions. That being said, the couple gravitates toward what they like. "We didn't go looking for antiques or art with any particular objective. The house seems to tell us what it wants," asserts the wife. Among her most cherished objects are early Delft ceramics, which she favors because of their soft coloration of reds, yellows, and blues, and because their aesthetic is appropriate to the house.

|

|

|

Though the building dates to the Federal period, the interior woodwork of the renovated music room features Georgian raised paneling with "tombstone" details, fluted pilasters, carved rosettes, bolection molding around the fireplace, a shell-carved cupboard, and, on the balcony level, acorn drops, finely turned balusters, and arches with decorative keystone detail. The palette, drawn from historic paint colors found at Stratford Hall in Virginia, determined the hues in the custom needlepoint carpet, upholstery, and period "furniture check" fabric used on the seats of a set of four Salem, Massachusetts, Chippendale side chairs; two shown. The still-life painting above the fireplace -- Stilleben mit Frichten und Blumen ("Still Life with Fruit and Flowers") -- is by Dutch painter Isaak Soreau (1604-1645). Flanking it are two anonymous portraits of unknown sitters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A candlestand attributed to the Dunlaps of southern New Hampshire is paired with a maple tall case clock signed by Levi and Abel Hutchins of Concord, New Hampshire, (working together from 1786-1807). They are placed at the base of the stairs leading to the balcony of the music room. In the foreground, English pewter sits atop a Pennsylvania Walnut dressing table from H. L. Chalfant. The successful form features a top with notched corners and molded edge, stop-fluted chamfered corners, shaped skirt, shell-carved legs, and trifid feet. A drop-leaf table against the nearby wall echoes the shaped corners of the dressing table's top.

|

Following the classic idea of the hierarchy of rooms, the most elegant furnishings are in the main public rooms, while more rustic country furnishings are in the First Period rooms in the ironmonger's house. Throughout the home there is an impressive array of tall clocks, case pieces, chairs, candle stands, and tables. In the Federal dwelling, a two-story space rimmed by a balcony (built by the previous owner) and referred to by the couple as the music room, commodious upholstered pieces create comfortable vantage points from which to admire the period furnishings. Lighting the room is a stately Dutch brass chandelier. Says Cottrell, who was at the house during the interview, "I like rooms that look like they happened over a long time; those that combine collections of many different periods and styles that work well together.

The wife has arranged the decorative objects in her home in appealing vignettes. "The house was much fuller," she recalls. "As the decoration evolved, I thought of Coco Chanel, who said [when dressing to go out], 'Put on your jewelry and take one thing off.' In a house, you need to create space around the objects so they can be appreciated."

|

|

|

|

LEFT: A spectacular Newport, Rhode Island, ball-and-claw foot high chest, from Wayne Pratt, Inc., is flanked by an early eighteenth-century Pennsylvania maple day bed from H. L. Chalfant. Two bird-cage tilt-top tables also share this corner. RIGHT: A Connecticut block-front secretary, possibly made in Woodbury, dominates this corner of the music room. The circa 1770 maple side chair has the distinctive form characteristic of chairs associated with William Savery of Pennsylvania. A portrait of an unknown woman watches over a drop-leaf table, a candlestand, and an English easy chair, one of two in the room.

|

|

|

|

|

LEFT: The Warham Williams house ell contains the formal dining room, which, says designer and preservationist John Cottrell, "Has to be flexible. Whether it's holding four, six, eight, ten, or twelve people, it should never feel awkward." The dining chairs, upholstered for comfort, are augmented when necessary with reproduction country Chippendale chairs; six of the set are used in the dining room and six on the balcony of the music room. The fireplace, one of six in the Williams' ell and house, retains its Georgian-era bolection molding. The room's early construction features main cross beams decorated with a chamfer ending in a "lamb's tongue," a treatment seen during an era when framing members were intended to be exposed. RIGHT: The sitting room is where the couple often relax, which makes sense given its cozy environment. The original raised field paneling surrounds a massive fireplace, which displays a collection of iron cooking pots and trivets purchased from the late Pat Guthman. An array of early furnishings include, in the foreground, a William and Mary gate-leg table and a ladder-back chair with sausage turnings; another table at the far end of the room is surrounded by four upholstered back stools. Two portraits attributed to the Prior-Hamblin group hang over two ladder-back chairs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early pewter and redware is displayed in the "buttery," or storage room, so named not because butter was made here, but because barrels were originally called "butts," from the Latin "buttis" for casks. An early high chair displays wonderful form.

|

One favorite category of furnishings is antique side chairs, which, the wife remarks, "have such personality. They are as individual as people." Following eighteenth-century custom, chairs are moved to accommodate varied activities as they occur. These include the small concerts the couple is fond of hosting, as well as dinners in the home's formal entrance hall. "It's fun to be able to eat anywhere in a house. Life is about change and different experiences," Cottrell observes, adding, "A room is about interacting; how well it functions for two people or for many. Things must be grouped to allow variety and to encourage conversation. A room should always have comfort, interest and balance, and it should feel good to you."

Upholstery for the modern seating furniture includes period-appropriate reproductions of eighteenth-century toiles de Jouy and furniture checks. Should the couple decide to paper the walls, the original paper for the Warham Williams house is in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum in New York, and could be used as reference. This couple chose paint; a soft palette of yellows, blues, reds, and greens on the woodwork to emphasize the architecture, white on the walls to showcase the collection. The golden yellow, which Cottrell describes as "a staple of eighteenth century ballrooms," and the other colors used in the house, were drawn from historic colors yielded by paint analysis at Stratford Hall in Virginia.

|

|

|

|

LEFT: This room in the ironmonger's house connects via a short flight of stairs to a period barn containing a library sitting room; notice the thick stone wall, originally the exterior wall of the barn. The seventeenth-century structure features details typical of First Period construction: post-and-beam framing, exposed framing members, a floorboard ceiling, heavily turned balusters, and drops. A ladder-back armchair and unsigned maple tall case clock are among a small number of objects in the space. RIGHT: The library is located in a restored barn, which exhibits exposed post-and-beam framing and casement windows. A simple staircase leads to a loft. The beams of the ground floor are perfect shelves for English pewter, blown glass bottles, and several paintings by the lady of the house. Furnishings include a Connecticut chest of drawers, Queen Anne armchair, and a maple tavern table, combined with a modern sofa upholstered in toile de Jouy.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The attic of the ironmonger's house has the perfect proportions for child-size furnishings and period toys. The exposed framing reveals wide-board roof sheathing and beams joined with wooden pegs known as "tree nails"; original casement windows provide ventilation.

|

Preferring comfortable, visually appealing interiors that appear to have evolved naturally over time, the couple sought the same approach in the landscaping, designed by Deborah Nevins. "They wouldn't have played tennis in the eighteenth century, so we don't have a tennis court," the wife says. "Deborah tried to restore the landscape in the most natural way. She really understood the place. If a tree didn't belong, it was gone."

The same can certainly be said of its owners and of designer John Cottrell, who has a history of restoring historic buildings. "Everything about this house is perfect to me," he says to his patron. "There was so much respect for what was here. [This house] is fortunate to have you."

"Some of these buildings have lasted for three hundred years," replies the lady of the house. "Someone who didn't understand their significance and history could ruin them. That would be a sacrilege." She adds, "It is a privilege and responsibility to take care of this place for whatever time we are allowed to care for it."

|

|

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format    Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|

|