A Year Recording Native American Life in 1874 : Jules Tavernier's Artistic Journey

Jules Tavernier, Harper's Weekly, and Red Cloud Agency

This is an archive article from Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

“I am about to cross one of the wildest regions [of the West], where no artist has gone yet,”Jules Tavernier (1884‒1889) wrote his mother from Cheyenne, Wyoming, on May 7, 1874. The next day he was to embark on a dangerous month-long journey into Indian Territory, the region west of the Mississippi set aside for habitation by Native Americans under the Indian Intercourse Act of 1834.

Imagine the thrill of adventure for this Paris-born artist. In 1873 Tavernier had traveled to New York and had worked as an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly. He had been hired, together with compatriot and fellow artist Paul Frenzeny, for a remarkable year-long sketching assignment that had taken the two by horse, coach, and train from New York to the Mississippi River, across Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and all the way to Colorado and Wyoming. From Cheyenne, Tavernier’s destination was Red Cloud Agency, Nebraska. Agencies were set up to issue supplies to both treaty and non-treaty Native American tribes in exchange for lands ceded to the U.S. government in 1868. Red Cloud Agency, established in 1873, was one of the largest of its day with between 9,000 to 13,000 Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho camped in its vicinity. It was named for Chief Red Cloud (Fig. 1), sometimes referred to by historians as “the Napoleon of the Sioux.”

The journey to Red Cloud Agency must have promised a sensational finale to their coast-to-coast sketching assignment. The artists must have felt that their sketchbooks of the American West were incomplete without images of “true" Indians. The appeal of the West and of its wilderness was quite strong for Europeans. Native Americans in particular were an object of fascination, a sentiment that is clearly reflected in another line of Tavernier’s letter: “I am going to see Red Cloud, one of the biggest Indian chiefs, and two or three others, I will really see life in the wilds.”

It was probably while wintering in Denver that Frenzeny & Tavernier had come into contact with “Indian trouble,” which had developed on the road between Fort Russell and Fort Laramie. A woodcut, Driven from Their Homes—Flying from an Indian Raid (Fig. 2), attests to the artists’ presence in the vicinity of the forts when clashes between Native Americans and settlers occurred there in late February and early March of 1874. The jointly signed work appeared on April 11, 1874, in Harper’s Weekly, with commentary by the artists: “…Our sketch represents an incident that took place during the march of a scouting column that left Fort Russell a few weeks since for Fort Laramie. On the march of ninety miles the brave boys in blue met many parties of refugees flying from the savage enemy. The cold was intense, forty degrees below zero, and the fugitives suffered the most cruel hardships. In our sketch the officer in command of the troops is gathering from a party of fugitives information concerning the whereabouts of the Indians.”

This was the region Tavernier was about to enter with Paymaster Major Thaddeus H. Stanton1 and a heavily armed escort of ninety cavalry men and ambulance cars. The paymaster was bringing with him $200,000 to pay the troops garrisoned at the forts of that frontier area. He would then, according to Tavernier, oversee several Indian Agencies, including that of the formidable Chief Red Cloud. What made this tour of duty special was that it would coincide with the annual Sun Dance, an ancestral rite performed by Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe honoring the sun. Thousands were to gather near Red Cloud Agency for the three day ritual, to which Tavernier had an invitation.

In the context of the tenuous relations between Native Americans, settlers, and soldiers, Tavernier’s invitation was exceptional. Major General William Harding Carter, commander of Camp Robinson, Nebraska, (the army post close by Red Cloud Agency), had secured the invitation. In his written account of his time at the camp, he commented, “With considerable difficulty I obtained consent to let Tavernier [sic] view the proceedings of the Sun Dance.”2 No doubt the name of Harper & Brothers, the prominent New York publishers who had founded Harper’s Weekly in 1857, was crucial in persuading Major Carter to go to the trouble. That the invitation was obtained for Tavernier may have honored the fact that he was the better painter. But in his letter to his mother, Tavernier mentioned that Frenzeny had not acclimatized to the altitude, and so may have been eager to move to lower ground.

The sketching companions split up for the first time in ten months. Frenzeny went on to Utah and California, where he produced, under both their names, a series of sketches. Tavernier’s subsequent sketches were also published under both their names. This arrangement no doubt fulfilled their contract with Harper’s. But Tavernier also filled his sketchbooks with scenes he would later turn into paintings, as he confided in his letter to his mother, “…if I come back in one piece, I hope to earn a small fortune with these sketches.” Tavernier’s excitement was no doubt fraught with apprehension. He had witnessed the hardships caused by the raids earlier that year and had undoubtedly heard the officers’ stories about their dangerous missions in the Territory and of the recent death of a fellow officer. Tavernier was probably also aware that most tribal Native Americans resented having their likeness drawn and that their mood would be at its most volatile at this great gathering of the clans.

The company left Cheyenne only a few days after Tavernier wrote his letter, traveling forty miles a day. They reached Fort Laramie in two days, where Tavernier spent perhaps as much as a week while the paymaster visited Fort Fetterman. The Parisian occupied his time by painting an interior scene of the fort’s trading store (Fig. 3), executed on the lid of a cigar box—canvas supplies were no doubt scarce on the frontier. It is reasonable to assume that this work was traded for goods at the store.

After a two day ride, Colonel Stanton’s party reached Camp Robinson, Nebraska, on May 20, 1874. This camp, located seventy-five miles northeast of Fort Laramie, had just been moved a mile and a half west of Red Cloud Agency and already had a history of dealing with tensions between Native Americans and encroaching settlers.

The woodcut An Indian Agency—Distributing Rations (Fig. 4), gives an idea of the agency’s warehouse and of the simple way provisions were distributed: published in the November 13, 1875, issue of Harper’s Weekly, this sketch does not bear the usual “Frenzeny & Tavernier” signature, but it is most likely the work of Tavernier. It was published with the following caption: “…Once a month a crowd of Indians, most of them squaws, assemble at the agency to receive their allotted rations, consisting of flour, coffee, sugar, beef, etc., and return loaded down to their respective homes.”

A little-known, unpublished sketch dated June 11, looking very much like a page from Tavernier’s sketchbook entitled “Tente pour la cuisine,” (Fig. 5) depicts the cook’s tent at Camp Robinson. The primitive tent and set-up depicted in this scene confirm that the fort was only now being established, it was still a mere tent encampment where cooking was carried out over an open campfire. Tavernier’s “Red Cloud’s Camp” watercolor (Fig. 6) dedicated to “my little friend Woolworth,” further depicts the temporary conditions the garrison lived in: a man works at a table in a tent, most probably intended as an infirmary since its shelves are filled with medicine bottles. These drawings provide rare glimpses of daily life at the camp at the time, and of Tavernier’s growing acquaintance with both Native Americans and infantry. A tintype taken by Lieutenant Thomas Whilhem of the 8th Infantry show the artist in riding boots and Stetson, sitting at the feet of Native American chiefs and military officers (Fig. 7).

The great Sun Dance brought out a wilder—and for the whites more unsettling— side of life at Red Clouds. This was the biggest religious ceremony of the year, with at least 15,000 to 20,000 Native Americans from different agencies in attendance, among them Red Cloud’s Ogallala Sioux and Spotted Tail’s Brulé Lakota. Tavernier was one of the first artists, if not the first, to attend the spectacular occasion, represented by his Indian Sun Dance (Fig. 8) sketch published in Harper’s Weekly on January 2, 1875. The impressive cathedral-like ceremonial tent is one of the most striking elements of the scene. In the comments that accompanied the sketch Tavernier described it as, “a round enclosure of high poles interlaced with branches and covered with buffalo skins. In the center of the arena stands a tall pole, which has been selected by a young Indian maiden and cut down with great ceremony. It is adorned with flags of white and red cloth, and at the top, during the first day of the rites, are fixed rudely carved representations of a man and a buffalo.”

Tavernier’s illustration and commentary records the extraordinary ritual performed on the last day of the ceremonies inside this structure. “[T]he young warriors of the tribe undergo various self-inflicted tortures for the purpose of proving their powers of endurance—such a piercing the skin and sticking into the wounds pieces of wood to which stout cords running from the central pole are attached. The whole weight of the body is suspended on these cords, producing the most excruciating pain, which is borne not only without flinching, but with every manifestation of delight. Others are fastened to their ponies in the same manner and dragged round the arena. All these young warriors are naked, with the exception of a cloth about the loins, and their bodies are smeared with red, green, yellow and blue paint.”

Tavernier’s Indian Sun Dance records the concentration of the crowd that surrounds the young warriors. Shown in relative darkness, they lend a strong sense of a community fully united by the ritual. His commentary explains the scene. “All this time the old warriors, who have been through the same trial in their youth, try to encourage the young bucks by beating drums and singing war-songs. The medicine-man stands ready with drugs and herbs to revive those that succumb to the torture. The squaws, adorned with green wreaths, and carrying boughs in their hands, encourage them with approving cries, and throw them presents in token of admiration.”

The three-day rite must have been quite a test of endurance for Tavernier as well. It ended at sundown on the third day with “a grand carouse.” According to Tavernier, “Very often the Indians go on the war-path the morning after the sun dance.” This was the case after this ceremony. Tavernier’s description did not disclose an incident that may have caused the Native Americans' unrest. Carter reported that “a violent storm came up and lightning struck the center pole. We were immediately warned to leave the vicinity as many of the hostiles alleged that our presence at the dance had caused the Supreme Being to register his disapproval by sending lightning to strike the pole around which they were carrying on their ceremonies.”

This incident could have cost Tavernier his life. But the mood calmed, and the artist was able to remain in the area and continue filling his sketchbooks with scenes of Native American life he later turned into resplendent oils (Fig. 9). Tavernier returned to Cheyenne some time around mid-June. He then set out to meet with Paul Frenzeny in San Francisco, where a new page in his western adventures would soon open.

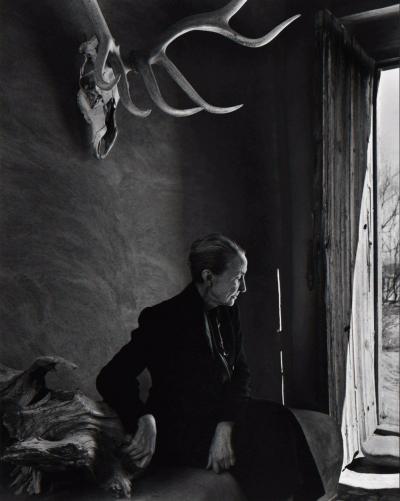

According to accounts from several of Tavernier’s fellow artists, the visit to Red Cloud Agency and the Sun Dance rituals in particular, made a profound impression on Tavernier. Tavernier’s San Francisco studio at 728 Montgomery Street exhibited many relics brought back from Red Cloud’s, mementos which became an inexhaustible source of inspiration for him. A San Francisco Chronicle reporter recorded her impressions of Tavernier’s studio in 1881, “The floor is bare save from some worn buffalo robes decorated with quaint geometric designs in bright mineral paints… [hanging in a corner are] beaded moccasins and belts or full buckskin suit. A magnificent warrior’s wampum bristling with eagle feathers hangs beside a lady’s soft changeable silk…”

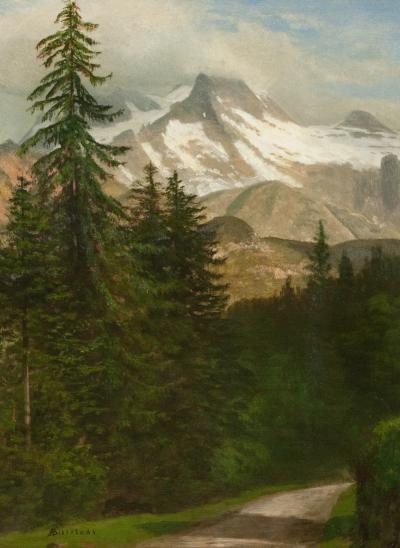

Tavernier’s canvases of Native Americans showcase his highly trained sense of color and composition, but also his keen attention to telling details and cultural accuracy; skills he developed while working with Frenzeny as a special correspondent—the two Frenchmen by now knew the Western frontier better than most men of their days. This combination impressed critics and collectors alike. The San Francisco Post art critic called him “a close observer and student of nature and at the same time an artistic poet. He catches the spirit and impression as well as the bare portrait of the scenery.” This admiration resulted in his canvases fetching high prices, even when they were unfinished, as happened with his Sioux Encampment (Fig. 10), purchased for $1,000 in 1884.

Tavernier painted Native American scenes for the rest of his career: from his studio in San Francisco; in Monterey where he founded an art colony (the Monterey Peninsula Art Colony); even from his studio in Hawaii in the late 1880s (Where he died in 1889) (Fig. 11). Against his expectations, he would never return to France and never again see his mother. The letter he wrote her so spontaneously from Fort Laramie to share both his excitement and apprehensions at the onset of his great adventure is the only letter in his family’s keep. It celebrates a time in Tavernier’s career when he accomplished the near-impossible, seeing “life in the wilds,” a feat many of his fellow artists longed to do, yet few had the good fortune to achieve.

-----

Dr. Claudine Chalmers is an independent scholar with a special interest in California’s French heritage. She is author of the award-winning book Splendide Californie, Impressions of the Golden State by French Artists, 1786–1900 (2001). Her work can be viewed online at www.FrenchGold.com.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2007 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Major General William Harding Carter, “History of Fort Robinson,” cited in Thomas Buecker’s Fort Robinson and the American West, 1874–1899 (Nebraska State Historical Society, 2003).