|

| Home | Articles | Art Focus: American Still Life -- Part 2 -- The Late Nineteenth Century |

|

|

|

PART 2

|

|

by Erik Brockett

|

For most of the nineteenth century American still life painting celebrated the nation's rich natural bounty. Typical subject matter included the fruit-filled tabletops in works by Raphaelle Peale (1774-1825) and James Peale (1749-1831); the luxurious mealtime spreads of John F. Francis (1806-1886); and Severin Roesen's (circa 1815-1871) opulent floral arrangements. In the 1870s, however, still life painting witnessed a significant change, reflecting the tumult of Reconstruction, industrial development, and an environment in which political and financial corruption were rife.1 For subject matter, still life artists now turned to material possessions representing leisure and business. Often these man-made objects were captured with impressive illusionism, resulting in a trompe l'oeil effect practiced by a number of painters. Although technically virtuosic, critics dismissed these -- frequently humorous -- works as visual trickery and they were considered of little significance well into the twentieth century.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: William Michael Harnett (1848-1892), The Social Club, 1879. Oil on canvas, 13-1/4 x 20-1/4 inches. Signed and dated lower left: "W M Harnett / 1879." The Manoogian Collection. Courtesy Vero Beach Museum of Art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: John Frederick Peto (1854-1907), Still Life with Candlestick, Book and Pipe, 1892. Oil on artist board, 9-1/4 x 6-1/2 inches. Signed and dated upper left: "J F Peto / 92." Courtesy of MME Fine Art, LLC, New York, N.Y.

|

One of the most influential American still life painters of the late nineteenth century was William Michael Harnett (1848-1892). He was born in Ireland, but raised in Philadelphia, where he was trained as an engraver of silver and attended classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In 1871 he moved to New York City, where he studied at the National Academy of Design and the Cooper Union. Although he continued his work as an engraver for several years, by 1874 he was able to devote his full attention to painting and returned to Philadelphia to resume study at the Academy. Until about 1880 Harnett's still life paintings, small in format, are identifiable by their cluttered tabletops featuring everyday objects rendered with meticulously detailed brush work. Harnett's The Social Club, 1879 (Fig. 1), a lively composition of pipes and matchsticks captured in pleasing tones, is a strong example of his tabletop work. (This image is a highlight from "The Reality of Things: Trompe L'Oeil in America" on view at the Vero Beach Museum of Art, Vero Beach, Florida until May 6, 2007.) His concern for precision in presentation of surfaces continued through the next phase of his oeuvre in which he focused on "rack" paintings. Recalling a seventeenth-century Flemish tradition, rack paintings typically show a grouping of two-dimensional items attached to a vertical surface by a pattern of ribbons; the objects appear to stand forward from the picture plane, creating a trompe l'oeil result. In 1880 Harnett traveled abroad, living in London, Frankfurt, and Munich, where he encountered the works of the Old Masters. His subsequent compositions increasingly included exotic and aged objects recorded in rich, mellow tones. Harnett's later work was characterized by the simplicity of a single object against a monochrome surface. Following his return to America in 1886 he established his residence in New York City, where he lived and worked until his death.

Unlike Harnett, John Frederick Peto (1854-1907) received little public attention during his lifetime, although his rack paintings display a technical ability that rivaled those of his more famous contemporary. Born in Philadelphia to a father who was a dealer in picture frames, the largely self-taught Peto enrolled in classes in 1877 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he was influenced by Harnett's work. Over the next several years Peto maintained a studio in Philadelphia and exhibited at the Academy's annual exhibitions. The everyday elements presented in Peto's still lifes are rendered with careful attention to the effects of light and demonstrate unlabored brushwork. His Still Life with Candlestick, Book and Pipe, 1892 (Fig. 2) contains the familiar domestic items for which Peto is known and exemplifies his mature style.

|

|

|

|

|

|

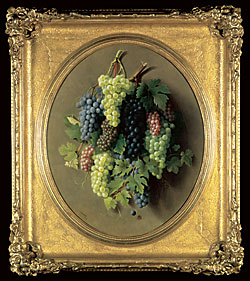

Fig. 3: Hannah Brown Skeele (1829-1901), Hanging Grapes, 1866. Oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches. Signed and dated at lower left: "H.B. Skeele. / 1866." Courtesy of Brock and Co., Carlisle, Ma.

|

Peto's choice of objects, often represented in a state of disarray and worn from use, were considered pedestrian by the buying public and resulted in his limited commercial success. In the late 1880s he began visiting Island Heights, New Jersey, where he built a house and lived a secluded life, supporting his family through the sale of his paintings at a local drug store and augmenting his income by playing the cornet for Methodist revival meetings. Shortly before his death, Peto sold a group of his paintings to an unscrupulous Philadelphia art dealer who added Harnett's name to them and sold them as the work of the better known painter. These spurious examples of Harnett's work were accepted until the 1940s when, through the scholarship of Alfred Frankenstein, they were shown to have been executed by Peto.

Although both Harnett and Peto are viewed as the pioneers of rack composition in America, this format was foreshadowed in the work of Hannah Brown Skeele (1829-1901). Born in Kennebunkport, Maine, little is known about her artistic instruction, although it has been established that she lived in St. Louis, Missouri, from about 1858 to 1871, during which time she possibly worked with Sarah Miriam Peale (1800-1885). Created a decade prior to the regular appearance of rack paintings, her Hanging Grapes, 1866 (Fig. 3) is an engaging fusion of innovative compositional effects and the accurate documentation of nature promoted by John Ruskin (1819-1900) during the late 1850s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

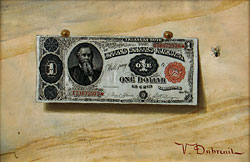

Fig. 4: Fig. 4: Victor Dubreuil (fl. 1880-1910), Trompe L'Oeil Still Life with Dollar Bill and Fly, 1891. Oil on canvas, 8 x 12 inches. Signed lower right: "V. Dubreuil," dated 1891 on bill. Courtesy of Godel and Co. Fine Art Inc., New York, N.Y.

|

Little biographical information has been established about trompe l'oeil specialist Victor Dubreuil (fl. 1880-1910). The son of French immigrants, it is known that he lived in New York City between the mid-1880s until at least 1896, frequenting the Times Square area. Although he painted illusionist still life elements usual for the time, his preferred subject was paper currency. His trompe l'oeil depictions of bills bundled together, overflowing from barrels, neatly arranged in piles, or shown singly, likely reflect Dubreuil's frustration with his impoverished circumstances. His Trompe L'Oeil Still Life with Dollar Bill and Fly, 1891 (Fig. 4), possibly a commentary on the public's distrust of Treasury notes, demonstrates his ability to realistically depict a technically difficult subject.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: De Scott Evans (1847-1898), A Plate of Onions, 1889. Oil on canvas, 10 x 12 inches. Signed and dated lower right: "Evans 1889." Courtesy of Godel and Co. Fine Art Inc., New York, N.Y.

|

A counterpoint to the focus on man-made objects in the period is presented by a number of artists who chose fruits and other produce as the subjects for their highly realistic works. Although known better during his lifetime for his representations of elegant women, De Scott Evans (1847-1898) also produced rack paintings. Born David Scott Evans in Boston, Indiana, he attended Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, where he received artistic training. Evans painted portraits while teaching at Smithson College in Indiana and Mount Union College in Ohio, before moving to Cleveland, Ohio, some time around 1874. By this point he had Gallicized his signature to "De Scott Evans" and within a few years went to Paris, where he studied with Adolphe-William Bouguereau (1825-1905). In 1877 he returned to Cleveland, where he flourished as a portrait painter and taught at the Cleveland Academy of Fine Art, becoming its co-director before relocating to New York City in 1887. Although it is known that he painted tabletop still lifes in Cleveland, after his arrival in New York City, he began painting trompe l'oeil pictures of fruit hanging from string and peanuts stacked behind panes of glass. Paintings by Evans are variously signed "Scott David," "S. S. David," or "Stanley S. David." The use of a pseudonym may have allowed the artist to distance himself from his commercially successful, but critically slated, trompe l'oeil compositions. Evans exhibited at the National Academy of Design, the Brooklyn Art Association, and the Salmagundi Club. Evans' A Plate of Onions, 1889 (Fig. 5) balances his trompe l'oeil style with that of his more conventional tabletop still life paintings. Signed "Evans," it is possible that the artist felt sufficiently pleased with his accurate handling of the translucency of onionskin to attach his name to the canvas. He died at sea while on his way to Paris.

|

|

|

|

|

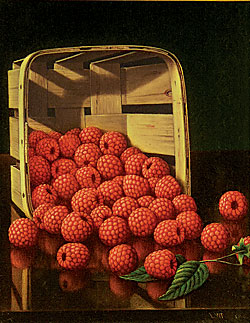

Fig. 6: Levi Wells Prentice (1851-1935), Basket of Raspberries, circa 1895. Oil on canvas, 10 x 8 inches. Signed lower right: "LW Prentice." Courtesy of MME Fine Art, LLC, New York, N.Y.

|

German-born Joseph Decker (1853-1924) lived most of his life in Brooklyn, New York, but studied at the Munich Academy. His early work, hard-edged and noted for its strong colors, contrasts markedly with his later paintings, which employ a softer, more classical approach. This change is likely the result of criticism of his earlier manner for seeming cold and detached.

Although Levi Wells Prentice (1851-1935) painted landscapes and portraits early in his career, after moving to Brooklyn, New York, from Buffalo, New York, in the 1880s his preferred subject became still-life arrangements. Prentice's Basket of Raspberries, circa 1895 (Fig. 6) exemplifies the artist's preference for carefully staged compositions rendered with exacting draftsmanship.

William Joseph McCloskey (1859-1941) studied at the Pennsylvania Academy, and over his lifetime lived in a number of both East and West Coast cities. Although he enjoyed success as a portrait painter, he is best known for his tabletop still lifes in which his subjects rest on highly polished wood surfaces. The artist's aptitude for capturing the texture and transparency of the tissue paper in which fruit was wrapped for shipping earned him the title "Master of the Wrapped Citrus."2

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), The Copper Urn, circa 1904. Oil on canvas, 35 x 40 inches. Signed lower left: "William Merritt Chase." Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York, N.Y.

|

The artists of the trompe l'oeil school were not the only practitioners of still life painting in late-nineteenth-century America; other artists embraced a more painterly style. Among whom was muralist and stained glass window designer John La Farge (1835-1910), whose poetic depictions of flowers in the 1860s and 1870s are considered by some the pinnacle of American botanical representation, not for their visual accuracy but for their romantic sentiment. William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) and Soren Emil Carlsen (1853-1932) were two artists of the period who were critical to the continuance of the painterly tradition into the twentieth century. Both were profoundly influenced by their exposure to eighteenth-century painting while in Europe, specifically the works of Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin (1699-1779). Born in Indiana, Chase received drawing lessons from a local instructor at an early age and in 1870 studied at the National Academy of Design in New York City. He soon returned to the Midwest, where in St. Louis he produced still life paintings, which were embraced by local patrons who gathered funds to support Chase's study at the Munich Academy. Enrolled there between the years of 1872 and 1876, his experience at this institution led to his production of dramatic kitchen-themed works. Although he would visit Europe in subsequent years, Chase returned to New York City, where he began teaching and exerting a lasting influence on following generations. Chase's The Copper Urn, circa 1904 (Fig. 7), testifies to the extent of his achievement as a still life painter. Chase's most famous still life subject was dead fish, but even here his understanding of harmonious color and his ability to capture metal surfaces is expertly demonstrated.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Soren Emil Carlsen (1853-1932), Still Life with a Brass Kettle, 1904. Oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches. Signed and dated lower right: "Emil Carlsen 1904." Courtesy of Schwarz Gallery, Philadelphia, Pa.

|

Described during his lifetime as "unquestionably the most accomplished master of still-life painting in America,"3 Soren Emil Carlsen was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, and emigrated to the United States in 1872. He worked as an architectural draughtsman in Chicago before returning to Europe in 1875, where he studied in Paris for six months. Gaining increasing recognition for his still life works in the United States, he returned to France in 1884 and stayed there two years, painting floral arrangements that found a ready market in New York City. After spending several years teaching in San Francisco during the late 1880s, Carlson returned to New York City in 1891 and began teaching at the National Academy of Design. His Still Life with a Brass Kettle, 1904 (Fig. 8), in which pieces of pottery, glass, and metal of varying shape and size are gracefully arranged, epitomizes his tranquil, monochromatic canvases.

|

|

|

Erik Brockett is on the staff of Antiques and Fine Art Magazine. Previously he was involved in the research and sale of artwork and prints through commercial galleries and auction.

|

|

|

1. John Wilmerding, "Notes of Change, Harnett's Paintings of the Late 1870s," from William M. Harnett, published by the Amon Carter Museum -- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 1992, page 149.

2. William Gerdts, Painters of the Humble Truth Masterpieces of American Still Life (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1981) 207.

3. Arthur Edwin Bye, Pots and Pans or Studies in Still Life Painting (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1921) 213-214.

|

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format    Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|