|

|

|

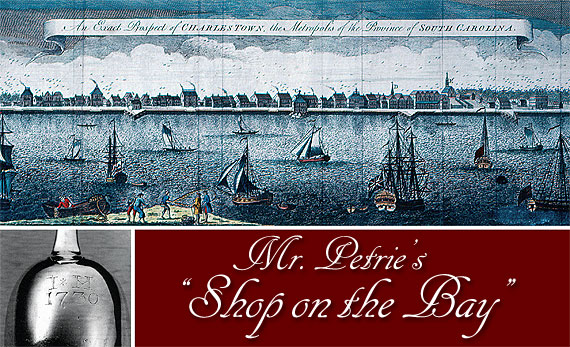

Fig. 1 (top image): "An Exact Prospect of Charles Town, the Metropolis of South Carolina," engraved for London Magazine, 1762, and based on a 1739 painting by Bishop Roberts (South Carolina, -1740). Courtesy of the Charleston Museum. This engraving shows the street lining the bay. Petrie's shop was slightly left of Half-Moon Battery, shown at the center of the engraving.

|

|

by Brandy S. Culp

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Coffeepot by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707-1768), circa 1745-1755. Silver, wood. H. 10-1/4 in. Courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the James Ford Bell Family Foundation Fund (1975.6).

|

In the bustling urban landscape of mid-eighteenth-century Charleston, a sizable artisan community, who satisfied the material and luxury demands of the city's cosmopolitan population, flourished. Among them was Alexander Petrie (ca. 1707-1768), whose store was prominently located along the bay between the city's most fashionable shopping thoroughfares -- Broad and Elliott Streets -- within view of Half-Moon Battery, the official harbor side entrance into the city (Fig. 1). It was a lively and diverse neighborhood, and Petrie ran a successful establishment selling fashionable imported English plate, jewelry, and watches, in addition to Charleston-made silver items, including articles made specifically for trade with Native Americans. Having arrived in Charleston by the early 1740s, Petrie was a respected gentleman by the time of his death in 1768. Today, he is one of the few South Carolina metalsmiths of the colonial era whose work survives in any significant volume and on whom a great deal of research material exists.

|

The survival rate for eighteenth-century Southern silver is low; however, approximately seventeen silver items with marks attributed to Petrie are known.1 Escaping the fate of much of Charleston's colonial silver, which appears to have been melted down for its intrinsic value, a few objects bearing Petrie's maker's mark made their way to England. They have since returned and include a coffeepot, several spoons, a small salver with unknown provenance, and a pap boat that most probably traveled from South Carolina to England with William and Sarah Middleton in 1754 (see Figs. 6, 8).2

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Punch Strainer by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707-1768), 1740-1750. Silver. Diam. 4, L. 7-1/2 in. Courtesy of the Charleston Museum (1983.76).

|

Petrie, long speculated to have been one of the many Huguenot craftsmen who settled in the South Carolina Lowcountry, was in fact from Scotland, most probably the Elgin area.3 Upon his arrival, Petrie benefited not only from his association with other transplanted Scots but from their connections too. One of the four extant coffeepots attributed to Petrie (Fig. 2) may have been made for a fellow Scot, as the finely engraved coat of arms on this example can be linked to the Allen (or Allan) family. Among the earliest Scottish families to settle in the South Carolina Lowcountry, the Allens of Charleston were noted for their affluence. Family members, including John (d.1748) and William Allen (d.1749), were active in the greater community as well as within traditionally Scottish organizations, such as the First Scots Presbyterian Church and the St. Andrew's Society, and they would most certainly have made Petrie's acquaintance.4

|

|

|

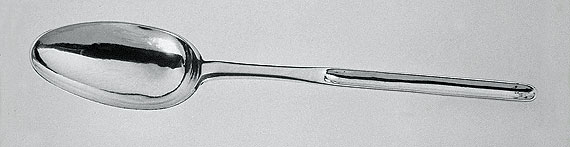

Fig. 4: Marrow Scoop Spoon by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707-1768), 1740-1750. Silver. L. 8-7/8 in. Courtesy of Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Old Salem Museum and Gardens (4544). The letter "K" is engraved on the middle of the handle, and the initials "I * H" with the date "1730" are engraved on the reverse of the bowl. This is one of the few colonial American examples. Charleston meltalworkers were advertising for sale similar spoon and scoop varieties as late as the mid-1750s, long after scholars understood the form to be outdated.

|

Where and from whom Petrie learned his trade is unknown, but evidence suggests that he was probably in his thirties and already a master craftsman upon arrival in Charleston. The first local mention of Petrie is found in Richard Woodward's will, dated December 14, 1742.5 Woodward conferred to his wife Elizabeth all his household silver, specifically noting "some other Pieces of Plate" that he had "sometime ago desir'd Mr. Alexander Petrie of Charleston aforesaid Gold Smith, to make for me." If Woodward had "sometime ago" commissioned Petrie, then, contrary to previous assumptions, Petrie either arrived in Charleston prior to 1742, or when he settled in Carolina, he was able to immediately establish his own shop and, therefore, did not work under the governance, guidance, or financial dependence of another Charleston silversmith.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Alms basin by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707-1768), circa 1755. Silver. H. 1-3/8, Diam. 9 in. Collection of St. Michael's Episcopal Church, Charleston, SC. Photography by Keith Leonard, courtesy of the Charleston Museum. The front is engraved "The Gift of HENRY MIDDLETON Esq./ to St Georges Church in Dorchester/1755;" a later inscription reads: "Presented to/ St. Michaels Church/by/ Henry A. Middleton Esqr./ Charleston S.C. April 1871."

|

Based on a stylistic analysis, two extant objects -- a punch strainer and a rare marrow scoop with spoon -- may date to Petrie's early Charleston career (Figs. 3 and 4). The furling leaf and scroll design of the sand-cast handles and the pierced twelve-petal flower decorating the bowl are typical of transitional objects made in the mid to late 1740s. Rum-based punch was a popular beverage in the Americas, and judging from the frequency that punch strainers were mentioned in advertisements and inventories, Charlestonians must have been particularly fond of the mixture.

In the first decade after his arrival, Petrie married, established a family, and expanded his business while steadily amassing capital, land, and slaves, one of whom was trained as a silversmith.6 In 1751, Petrie purchased the building that he had leased from John Watsone, and he and his family remained there until his death in 1768, even after he purchased the larger dwelling house next door in the late 1750s. Seemingly a commodious place, we can only identify two of the workers associated with the shop, Erskin Heron and Petrie's slave Abraham.

|

The diversity and geographical concentration of artisans in a small area within the city helped to hasten the exchange of new fashions. Thus, it is not surprising that Petrie, a Scottish silversmith, made a liturgical basin for an Anglican church that is reminiscent of a traditional French form (Fig. 5). The alms basin was commissioned by the socially prominent planter Henry Middleton (1717-1784) for St. George's Parish in nearby Dorchester. In 1755, Middleton was appointed to the South Carolina Council by the Crown; perhaps, he commissioned the alms basin to commemorate his entree into the colony's political elite as well as to celebrate the addition of the church's imposing new bell tower, built sometime in 1754.

|

The alms basin is an outstanding example of eighteenth-century American silver, and by far one of the most successful surviving examples of Petrie's work. While it has been compared to French jattes (basins), Petrie's alms basin surpassed that which he imitated. The undulating rim gives the illusion of a ribbon widely gathered around the flat dedication panel, drawing attention to the engraving of the patron's name in the center. Petrie's alms basin aided Henry Middleton in affirming his place within the congregation, and also asserted Petrie's talent and status as a superior craftsman.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Salver by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707-1768), 1750-1768. Silver. Sold at Christie's, May 19, 2005, lot 63, © Christie's Images, Ltd., 2006

|

The remaining body of Petrie's known work represents the average stock items he may have readily kept in his silver shop. These objects share a similar stylistic vocabulary with the work of his colonial contemporaries. The two small shell-and-scroll rimmed salvers with the requisite "AP" marks (see figure 6) are in fact remarkably similar to salvers made by New York silversmiths Myer Myers (1723-1795) and George Ridout (freeman 1745) and Philadelphia silversmith Joseph Richardson Sr. (1711-1784). Many notable mid-eighteenth century colonial silversmiths produced variants of the shell-and-scroll border that closely relate to imported examples from London workshops. The construction techniques employed by Petrie and his shop workers, however, are unique in comparison to other colonial-made examples. At least in two instances, Petrie made a large and a small waiter or salver with cast rims and feet that were both soldered and pinned together with thin metal rods, which today are only visible because of damage to the legs or wear along the surface of the rim (Fig. 6). American silversmiths are not known to have used this construction method. In overall appearance the small salver with pinning is almost identical to the Petrie example in the Museum of Southern Decorative Arts.

Other Petrie objects also exhibit eccentric design approaches. The marrow scoop in the collection of the Charleston Museum is one of very few American mid-eighteenth century examples with scooping channels facing in opposite directions. The single known cann, or mug, bearing the "AP" maker's mark was raised from a silver disk, but the foot was assembled by soldering together several silver pieces of varying width, rather than hammering or casting the base (Fig. 7). This stylistically transitional example with a slightly curving belly and furling handle terminus, descended within the noted Ravenel family of Charleston. At what point the Ravenel family acquired the cann is unknown, but perhaps it was at the same time that Daniel Ravenel purchased or received a coffeepot that was later inscribed "D. Ravenel./1776."7 Despite the engraved date, the style of the coffeepot is of the mid-1740s to mid-1750s, and the stamp placement and markings are undoubtedly those attributed to Petrie.

|

Several objects attributed to Petrie's workshop show that economy of time and labor was the favored mode. For instance, the four extant coffeepots attributed to Petrie are extremely similar in overall appearance and scale. All are characterized by elongated, pear-shaped bodies with tapering sides, simple flared-foot rings, low-domed covers capped with finials, cast scroll-and-leaf spouts, and ornately rendered cast handle-socket terminals (Figs 2, 8). Most importantly, Petrie constructed the bodies of sheet silver, which he joined in a vertical seam at the handle. This method was less skill-intensive and more efficient, since making the typical pot by raising the body took great ability and time. Petrie's construction method is uncommon in America for this time period, as the use of sheet silver did not come into wide use until the late-eighteenth century. However, silversmiths in England had adopted this method during the early eighteenth century.8 Initially seamed pots were constructed of hand-hammered sheets, but by mid century rolling mills were available in England and in some instances imported into the colonies.

|

|

|

LEFT, Fig. 7: Cann by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707-1768), 1745-1755. Silver. H. 3-3/8 in. Private Collection. Photograph courtesy of Decorative Arts Photographic Collection, Winterthur Library.; RIGHT, Fig. 7a: Detail of the maker's marks on the bottom of fig. 7.

|

At a time when most silversmiths began to give their coffeepots a rounder, fuller belly, Petrie's examples retained relatively cylindrical, slightly bulbous bodies, a design that was more conducive to production with sheet silver. It is quite possible that the material and construction methods dictated the form. Aware that "time was money," Petrie may have chosen the easiest and most time-efficient techniques -- seamed sheet silver and cast parts.

While three of the four known pots are plain-bodied, one was chased with broken C-scrolls and asymmetrical floral repousse designs (Fig. 8). This is one of only two known examples of eighteenth-century chased silver from South Carolina. The other example is a sugar bowl made by Thomas You (act. c. 1753-c. 1786) for Daniel and Mary Cannon. In comparison, Petrie's work is more complex with repousse adorning the surface in addition to chased flowers, floral sprays, and C- and S-scrolls.9 While Petrie's coffeepot is the only surviving example of such a decorated form made in Charleston, there are numerous advertisements in the South Carolina Gazette for "silversmiths work, both chased and plain."

Much of what we know about Petrie's actual silversmithing shop comes from the period at the end of his career when he had begun to diversify his interests, and silversmithing no longer seems to have been his main focus. Based on two references from the South Carolina Gazette, an advertisement by metalworker Jonathan Sarrazin (active c.1754-c.1790) and Petrie's death notice that stated he had "some Time ago retired," E. Milby Burton concluded that Petrie closed his shop in 1765 and other scholars have entertained this claim.10 A new reading of the evidence, however, suggests that in his late fifties, Petrie ceased importing and sold his existing imported stock to Sarrazin, and that he and/or his slave Abraham, a trained silversmith, continued to work in his jewelry, watchmaking, and silver concerns.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Coffeepot by Alexander Petrie (c. 1707- 1768), 1745-1755. Silver (chased and repousse), wood. H. 10-3/8 in. Courtesy of Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts. Old Salem Museum and Gardens (3996).

|

Given the political and economic circumstances in Charleston at the time it was perhaps no coincidence that Petrie abandoned his import business in 1765. In February 1765, after the repeal of the Sugar Act, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, causing tremendous political and social unrest in Charleston, since stamps were needed to clear incoming and outgoing vessels. Petrie made a timely exit from the import trade, as fierce riots ensued after October 1765 and there was a call to produce and buy American.

While Sarrazin acquired some of Petrie's stock on hand, Petrie clearly retained his storefront and left his workshop intact. At the time of his death, Petrie still owned his tools, some raw materials, as well as finished products, namely "1 New Chased Coffee pott [sic]," and approximately 1,166 items of silver destined for the trade with Native Americans.11

A month after Sarrazin's announced "that he has bought Mr. Petrie's stock on hand -- most of which has been but a few months in [the] province" in the Gazette, Erskin Heron, a London-trained silversmith, advertised that he was "late with Mr. Petrie" and was now located on Union Street. Heron's departure from Petrie's employ confirms that some type of reorganization occurred within the workshop in 1765. Perhaps after this, Abraham, able to manage the workload, continued to labor in the shop on the bay while Petrie tended to other business affairs.

Sarrazin made several purchases at Petrie's estate sale, the most notable of which was Abraham, who commanded a high price of £810 in South Carolina currency. The presence of several metalsmiths at Petrie's sale, including James Alexander Courtonne (1720-1793), Francis Gottier (active c.1741-c.1783), and Sarrazin, may account for this relatively high sum, since the desire to purchase Abraham may have driven up the bidding price, a testament to his proficiency as a craftsman.

After Sarrazin acquired Abraham, he began advertising "Indian trinkets," a line of goods he had not explicitly mentioned before. If Indian trade silver was one of Abraham's specialties, this is an explanation for why so much of it was listed in Petrie's inventory. Perhaps Petrie did not actively practice the trade himself, but allowed Abraham to continue working, which would explain why he did not dissolve his business completely. Had he entirely given up the trade, would it not have been to Petrie's economic advantage to dispose of his tools, disassemble his storefront and, more importantly, sell such a valuable slave as Abraham?

Petrie was not only a skilled artisan, but he was also a businessman, who used his talent to propel himself into the class of land-owning gentleman. From his shop on the Bay, he catered to sophisticated, wealthy customers who commissioned objects in the latest silver fashions as well as to clients who wanted ready-made, imported plate, trinkets, and jewelry. As with other successful Charleston metalworkers, his versatility as a retailer and reputation as a craftsman were the foundation of his success.

|

|

|

Brandy S. Culp recently joined the Historic Charleston Foundation as curator. She was previously the Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial Fellow in the Department of American Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. This article is extracted from her MA thesis, Artisan, Entrepreneur, and Gentleman: Alexander Petrie and the Colonial Charleston Silver Trade, for the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture, 2004.

|

|

|

1. Currently, silver attributed to Alexander Petrie bears two different maker's marks. Evidence strongly suggests that we can assume both marks are indeed Petrie's die stamp.

2. Many thanks to Robert B. Barker and Mary Edna Sullivan for bringing these objects to my attention.

3. Manuscript material in the Petrie family papers, including a birth register, an unpublished family history, and references to a family bible thought to have been brought from Scotland to the Americas by Alexander Petrie, supports the claim that Petrie was Scottish. In addition, period sources strongly suggest that he was among a network of educated and well-connected Scots, who were involved in varied political, social, and mercantile endeavors. George Petrie Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Ralph B. Draughon Library, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama.

4. Among silver valued at £825 in John Allen's estate inventory was a single silver coffeepot. Inventories, Charleston County, 1748-1751 (WPA Inventory Transcripts), South Carolina Reading Room, Charleston County Library, pp. 47-53.

5. E. Milby Burton brought this citation to attention in his book South Carolina Silversmiths, and thus far, this remains the earliest mention of Petrie to have been found in South Carolina records. E. Milby Burton, South Carolina Silversmiths, 1690-1860, revised and ed. by Warren Ripely (Charleston, SC: Charleston Museum, 1991), 77. South Carolina Will Transcripts (WPA), Charleston County, vol. 5, (originally recorded in Will Book 1740-1747, p. 199) South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, S.C., 341.

6. In 1748, Petrie, at the age of forty-one, married Elizabeth Holland, who was twenty years old. Through this union with "an agreeable young lady of great merit," Petrie established familial ties with two men of great note -- Daniel Crawford, a prominent Scot, and James Laurens, brother of the merchant and statesman Henry Laurens. We know that Laurens, Petrie's brother-in-law, purchased a great deal of silver at Petrie's estate sale, but no "AP" marked silver with a Lauren's provenance is known. Extract of an entry in a register kept at the General Registry Office, Edinburgh, 1874, in the George Petrie Papers, Auburn University Special Collections and Archives. Holland Family Marriage and Birth Registry, George Petrie Papers, South Carolina Gazette, February 8, 1748.

7. This coffee pot is a plain version of figures 2 and 8; it is in the collection of MESDA.

8. See the coffeepot by William Charnelhouse (free 1696; d. 1711-12) in the collection of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

9. While You's sugar bowl is the only example of Charleston silver with which to compare Petrie's chased coffeepot, there are other chased works made elsewhere that closely relate to Petrie's pot in both ornament and form. The most comparable example is a coffeepot made by John Inch (1741-1763) of Annapolis, Maryland. Although the ornamentation on the two objects obviously differs in many respects, they share the same basic form and Rococo vocabulary. Petrie's repousse and chase-work is, however, slightly more robust and heavy than Inch's, which is more delicate. For image see Jennifer Faulds Goldsborough, Silver in Maryland, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society, 1983), 132. Faulds compares Inch's coffeepot to an example found in Scotland at the Glasgow Art Gallery and Museum.

10. Burton, South Carolina Silversmiths, 148.

11. Petrie, Inventories of Estates, 365-369. South Carolina Gazette, 24 October 1768.

|

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format     Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|