Daniel Garber: Romantic Realist

This archive article was originally published in the 7th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

In the second decade of the twentieth century, artist Daniel Garber (1880– 1958) emerged as one of leaders of the New Hope School, also known as the Pennsylvania School of Landscape Painters. This handful of artists was tied together more by the location of their studios—in Bucks County, Pennsylvania—than by any one painting style. Garber, and the school as a whole, were heralded as the landscape painters of their generation, receiving critical recognition across the United States where they exhibited their works in the first quarter of the twentieth century; artist and critic Guy Pène du Bois observing in 1915 that their art was “our first truly national expression.”1

The group’s art was largely ignored for most of the mid to late twentieth century since it did not seem to fit perceptions of American modernism and its roots. Over the past quarter of a century, however, regional studies of American art have steadily included discussions of the New Hope school and other art centers.

Born in Indiana, Garber immediately after high school left his home state to attend the Art Academy of Cincinnati where he studied from 1897 to 1899 with two artists trained in the Munich school of late nineteenth-century realism. At the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he trained from 1900–1905, Garber’s primary mentor was Thomas Anshutz (1851–1912). Anshutz continued the traditions of American realist Thomas Eakins (1844–1816) and is sometimes best remembered as the teacher of many of the artists of the Ashcan School of urban realism.

Anshutz encouraged his students, including Garber, to seek their own artistic direction. After painting in a similar manner to his teacher, utilizing a dark brown palette and more conventional composition devices, Garber went his own way; unlike his New York contemporaries of the Ashcan School, however, he went on to explore realism in the country, depicting the rural landscape. This freedom encouraged by Anshutz also allowed Garber to develop a decorative formal style greatly unlike that of his teacher.

Garber created several large scale figure pieces depicting his daughter, Tanis. Here he has depicted her as if standing in a doorway of his studio at their home, Cuttalossa, in Bucks County. Beginning with Tanis, Garber began to explore the passage of light through air and objects. While perhaps looking like an “impressionist” painting, this work is not about fleeting light effects or impressions. As Garber recorded, the painting was worked on over all of the summer months of 1915, the artist apparently returning to the work when his general light effects could be recreated. With its frieze-like monumentality, the artist’s goal was to achieve a Golden Age depiction of childhood; an eternal idealized image, rather than a momentary real one.

Garber’s flexibility in style is evident when comparing Tanis to this image. At the same time that he was at work on Tanis, Garber painted The Boys. Depicting three of Garber’s students at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, this oil was created in his studio at Cuttalossa. Unlike Tanis, the picture relies on an artificial light source (located outside of the picture) to illuminate the scene. Garber also used preparatory studies on paper and in oil to create this work.

The Boys was sent by the artist on exhibition at the National Academy of Design in New York. Concurrent with the National Academy exhibition was an important memorial exhibition to Thomas Eakins. Critics recognized that Philadelphia artists, including Garber, were honoring Eakins by their submissions to the academy exhibition. Garber admired Eakins’s honest and direct approach to painting, and in this particular instance he created his work through extensive study and planning—methods learned from Eakins’s student, Thomas Anshutz.

Depicting solitary trees would become a liet motif for Garber, in particular complex trees whose twisted forms challenged the artist’s abilities as a draughtsman. Garber’s contemporary, and the dean of the Ashcan School, Robert Henri (1865–1929) wrote a “tree rising and spreading from its roots” is an “eloquent symbol” of life. “In a tree is a spirit of life, a spirit of growth and a spirit of holding its head up.” Buds and Blossoms is one Garber’s most decorative depictions of a solitary tree, one in which he incorporated flatness of composition with stylization typical of Oriental art.

Garber’s home was located within several miles of quarries that line the Delaware River in the Bucks County region of Pennsylvania. Throughout his career Garber depicted a number of these quarries. Of his many such compositions, The Quarry is particularly serene, with its still, intensely horizontal, composition.

Many of Garber’s landscapes depict views on the Delaware River. From 1911–1917, he created a series of large-scale landscapes on the theme of the trees that lined the river banks, all of which utilize a screen of trees placed in the middle ground of the picture. Hawk’s Nest, the final statement on the theme and painted in the same year as The Quarry, is the most pointedly stylized work in the series, with its limited palette and highly sensuous lines. At the time it was acquired by the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1920, Garber described this “decorative landscape” as the best of the group.

Although Garber’s most decorative landscapes were created in the 1910s, he remained interested in formal compositions throughout his career. Geddes Run depicts a view looking down to the Delaware River, with a view of New Jersey in the distance. As was frequently the case in Garber’s landscapes, he pulled the distant view “up” to the top of the canvas, showing more than can actually be seen from this vantage point. In contrast to the strong horizontal emphasis created by the blue river in the middle distance, Garber keeps our focus on the surface of the painting with the vertical rhythm of the slender tree trunks.

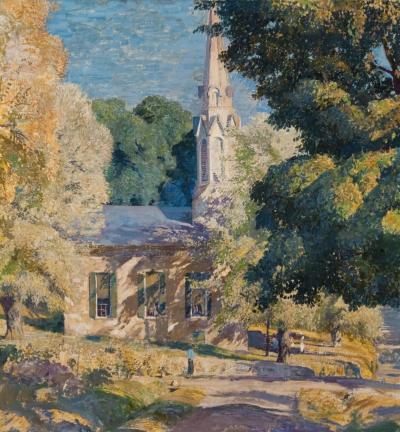

Garber was not a particularly religious man, but he was spiritual, believing that one could see a divine presence in the world. On a number of occasions he depicted this church in Stockton, New Jersey, perhaps less for the reason that it was a house of worship, but because he enjoyed its form, with its stucco surface and elaborate steeple. Notably, although the church rests at the edge of town, Garber always painted it as if to suggest it was a country church. Church at Stockton is an excellent example of Garber’s interest in painting “wet light”—the appearance of light as is travels through moisture in the atmosphere, as is the case here where he captured the kinds of atmospheric effects present on a humid summer day.

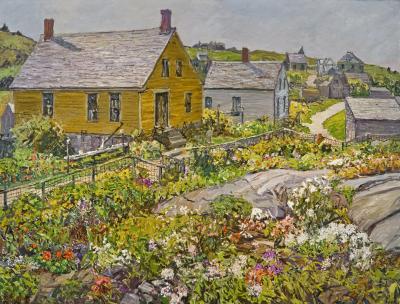

Garber’s landscapes from before 1930 seldom depict people. However, after the Depression began, he increasingly became interested in depicting people at work or at play, exploring the hard work and rewards found in the country and in country towns. This shift to a more narrative focus is one of the largest changes that occurs in Garber’s work after 1930.

Prior to settling in New Hope, Garber traveled overseas to paint in England, France, and Italy on a fellowship from the Pennsylvania Academy. On his return in 1907, he settled in Bucks County, an area he had been introduced to before his departure by the New Hope school artist William Langson Lathrop (1859–1938). The influences Garber and others brought to the area were noted in Dubois’ 1915 article, when the critic observed that the New Hope artists adapted the painting technique of the French Impressionists into a new style that was distinctively American. For instance, Garber could utilize the dab-like brushstrokes associated with the French Impressionists, while being disinterested in the notion of capturing a fleeting moment. This partial borrowing was consistent with his training and experience, as was his use, on occasion, of highly stylized and flattened compositions—an approach appreciated and understood by emerging promoters of abstract art.

The duality between his highly decorative and stylized impulse with what could be a blunt, straightforward manner, is perhaps best summed up by contemporary critics, who called his approach poetical or romantic realism. Indeed, some of Garber’s pictures are best described as “romantic,” others as “realism;” in some works he seems to have combined both approaches.

Although best recognized for his landscapes—which often depict representational imagery in a strong color palette favoring blues, greens, and yellows—as Garber matured he occasionally created figure pieces. Typically these were of Garber’s wife, Mary, or their daughter, Tanis; however in one exception the artist painted their son, John, depicted with his mother, Mary. Although these works bear strong likenesses to the sitters, they were not meant to be portraits; the individuals were meant to stand for universal themes and ideas. This was the case with his landscape work as well—Garber was searching for eternal and idealized notions of nature, rather than a photographic depiction of what he saw before him.

Garber exhibited widely throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century and was collected by major institutions across the country. After the beginning of the Great Depression, however, his art was incrementally set on the sidelines as many of the same museums that had supported and acquired his works began to reshape their collections of twentieth century art. Although Garber undoubtedly believed that this transition was a setback to his career, he continued to paint until nearly the end of his life—sending over 2,500 objects out on view to over 750 exhibitions during the course of his lifetime—a testament to his urge to create and to share his art with the public. This interest was also expressed by Garber’s forty one years at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he taught from 1909 until 1950, disseminating his knowledge and influence on succeeding generations of artists.

This essay is adapted from Lance Humphries, Daniel Garber: Romantic Realist (Philadelphia and Doylestown, PA: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and James A. Michener Art Museum), which in turn relies heavily on Daniel Garber Catalogue Raisonné, 2 vols. (New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 2006), also by the author. The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the James A. Michener Art Museum in Doylestown collaborated to present Daniel Garber: Romantic Realist. An exhibition that showed at the Academy from January 27 through April 8, 2007; and at the Michener from January 28 through May 6, 2007. The exhibition was split chronologically, with the works at the Academy examining the period of Garber’s oeuvre between 1897 and 1929, and 1930 through 1958 at the Michener Museum. For more information about this and other past exhibitions please visit www.pafa.org (215.972.7600) or www.michenermuseum.org (215.340.9800).

-----

Lance Humphries, Ph.D., is an independent scholar specializing in the arts of the Middle Atlantic region. In addition to his recent publications on Daniel Garber, he has published and lectured on members of the Peale family, Baltimore Painted Furniture, and the Baltimore art patron Robert Gilmor, Jr. He is currently consulting for Montpelier, James Madison’s home in Orange, Virginia, regarding the interpretation and installation of Madison’s art collection, and working on a book on Baltimore Town Houses 1780–1840.

This article was originally published in the 7th Anniversary issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. See Bayard Breck, “Daniel Garber: A Modern American Master,” Art and Life 11, no. 9 (March 1920): 492–97.