|

| Home | Articles | Investing in Antiques: Schoolgirl Needlework |

|

|

|

|

by Nancy N. Johnston

|

|

|

|

|

|

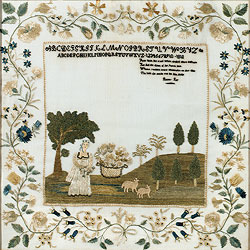

Fig. 1: Sampler, Fitzwilliam, NH, by Betsey Fay, 1818. Silk, chenille, metal, and painted paper on linen. 20-3/4 x 20-3/4 inches. Courtesy of Stephen and Carol Huber.

|

In the final chapter of her two-volume publication Girlhood Embroidery (1993), Betty Ring, the foremost authority on schoolgirl needlework, provides an in-depth history of collecting this art form, which she traces back to the 1860s. An early prominent collector was Alexander Wilson Drake (1843-1916). Samplers from his collection were exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery, Washington, in 1908 and at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1909. In 1913, when the Drake collection was auctioned at the American Art Galleries in New York, one of its highlights brought $57. At the Theodore H. Kapnek sale at Sotheby's in 1987, the first sale devoted solely to American needlework, the same piece was auctioned again for $44,000, yielding a respectable 9.4 percent compounded annually. To put this into perspective, a comparative rate of return for stocks over the same time period was 9.5 percent and 4.4 percent for bonds. Dealers of girlhood embroidery Carol and Stephen Huber of Old Saybrook, Connecticut, showed me the price history of a piece of needlework they handled several times dating back to 1974 by a girl named Betsey Fay (Fig.1). As lot 51 in the Garbisch sale at Sotheby's in 1974 it was sold to John Walton for $700. The Hubers acquired and sold the piece on a number of subsequent occasions. In 1977 they sold it for $3,500, and in 1999 the piece went for $65,000. The compounded rate of return over a twenty-five year period was an impressive annual 19.87 percent. Dealer Amy Finkel of M. Finkel and Daughter, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, sold twice over the last decade an 1804 sampler by Sarah Gaskell (Fig. 2). Ms. Finkel placed this masterpiece privately in 2003 for $400,000.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Sampler, Burlington County, NJ, by Sarah Gaskill, 1804. Silk, watercolor, and paper on linen, 17 x 17 inches. Sold into a private collection in 2003 for $400,000. Photography courtesy of M. Finkel and Daughter.

|

The earliest known American sampler was made in 1653 by Loura Standish, daughter of Miles Standish, military captain to the Plymouth Colony pilgrims. Today, heavily worn, it can be seen at Pilgrim Hall in Plymouth, Massachusetts. There are other seventeenth-century American samplers, but many resemble those made in England so it is difficult to identify their origin. In the early eighteenth century, as American society became more established, girls as young as five years old were sent to boarding or day schools where they learned, among other skills, the art of needlework. According to Ruth Van Tassel of Van Tassel/Baumann American Antiques, of Malvern, Pennsylvania, displays of needlework were testaments to a family's economic means and social status.

Schoolgirls in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had to master different levels of embroidery. The most basic were marking samplers with which the schoolgirls exhibited their knowledge of numbers and the alphabet. (These were not usually framed for display.) Young ladies then graduated to a form referred to as pictorial needlework. These were more complex and included intricate borders and mottos, the more elaborate examples replaced the alphabet with scenes of nature, idealized houses or schools, flora and fauna, and characters such as courting couples. At the turn of the nineteenth century silk embroideries became popular and involved silk thread on canvas (usually the earlier pieces), silk on silk, or the rarest, a combination of painting and silk on silk. These silk works often picture biblical scenes, fables, and mourning scenes.

|

Everyone interviewed for this article agreed that 99 percent of the value of a needlework rests in its graphic appeal. Condition and rarity are the next considerations. Unlike furniture, restoration is not forgiven in this field. Although condition plays a secondary role it is nevertheless very important when considering the value of a piece. Faking is not a widespread problem in silk embroideries but there are forgeries in marking samplers and to the untrained these are difficult to identify.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Sampler, Burlington County, NJ, by Hannah L. Hancock, 1840. Silk on linen, 17-3/4 x 20-1/2 inches. Photography courtesy of M. Finkel and Daughter. Recently sold for over $100,000.

|

Most of the known needlework was made by girls living along the east coast. No one school stands out as the best, but a number produced very developed and consistently dynamic work. These include the Boston area schools of Susanna Condy, Susanna Rowson, and Mrs. Saunders and Miss Beach's Academy; the Mary Balch School of Rhode Island; and, in Philadelphia, the (Samuel) Folwell School (silk embroideries and painting on silk) and the Elizabeth and Ann Marsh School (early samplers). Amy Finkel considers the Burlington County, New Jersey, area as exceptional for producing samplers that "are big and full and filled with Quaker motifs (Fig. 3)." Van Tassel included the Westtown School of Pennsylvania, founded in 1799 and still in existence. The specific layout of the lettering and use of Roman numerals makes the Westtown works exceptional. While some names on schoolgirl samplers are familiar, Ruthy Rogers, for example, no one schoolgirl is considered the best. In fact, according to Betty Ring, many of these schoolgirls only completed two or three works.

|

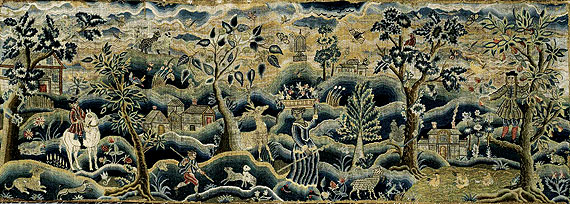

The record price to date is the $1,200,000 paid for the Hannah Otis over mantel canvas-work sampler sold in 1996 at Sotheby's.1 This piece, larger than normal in size and of freehand design, is outstanding as it depicts in elaborate detail the John Hancock House and Boston Common. Purchased by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, it is considered both a historical artifact and a work of art. Since then another over mantel canvas work (Fig. 4) sold at Bonhams and Butterfields in 2003. With an estimate of $20,000-$30,000 the Hubers purchased it for a client for $611,250. "Both are masterpieces," they say, explaining the difference in price between the Hannah Otis work and the canvas work purchased for their client, "and [both are] from the same unknown Boston school, but the one we purchased was not designed free hand, nor is it signed. The source for our piece was a print source, usually purchased by the teacher and transferred to the canvas. Highly developed, this example is one of eight known, with all others in museums." Ms. Ring describes the early canvas works as the most sought after as they were "Done by the very wealthiest of girls, usually including a multiple of colors which other schoolgirls simply couldn't afford."

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Canvaswork chimney piece, possibly the school of Susanna Hiller Condy (1686-1747), Boston, circa 1740. Wool and silk on linen, 16-3/4 x 47-1/2 inches. Photography courtesy of Bonhams and Butterfield. Purchased in 2003 by Stephen and Carol Huber for $611,250. This is the second highest price paid for a piece of needlework.

|

Generally speaking, American schoolgirl needleworks command a higher price than English works. According to Finkel, this is because "American samplers offer greater folk art appeal and are less formulaic than English samplers." Another reason is supply; far fewer schools were established in America than in England during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, hence American needlework is scarcer. The Hubers note that new collectors, in keeping with historic tradition, are acquiring silk embroideries to complement their collections of fine art and American furniture, while samplers and pictorials appeal more to those collecting folk art. The price for fine American schoolgirl needlework can range in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, but many quality pieces are available for between $10,000 and $50,000. Working with an expert in the field is a must.

|

|

|

|

Nancy N. Johnston is a private consultant and broker for art and antiques, and a

regular contributor to Antiques and Fine Art Magazine.

|

|

|

|

1. See Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery (New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 49, fig. 47.

|

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format     Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|

|