|

| Home | Articles | Intersections: Native American Art in a New Light |

|

|

by Karen Kramer

|

|

|

Not intended to provide a comprehensive history, the exhibit offers

three fresh perspectives from which to consider Native American art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

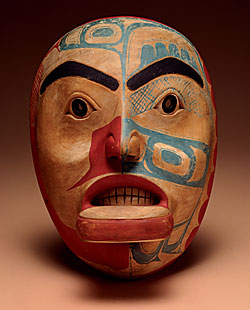

Fig. 1: Djilakons mask, Kaigani Haida artist, Village of Kasaan, Southeastern Alaska, circa 1820. Wood, paint. 10-1/4 x 7-1/2 inches. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; gift of Daniel Cross, 1827, E3483. Photography by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey Dykes.

|

The Peabody Essex Museum celebrates the opening of its new Native American gallery with Intersections, Native American Art in a New Light, an exhibition that crosses boundaries of time and geography, materials and techniques to explore meaning in Native American art. Founded in 1799 in Salem, Massachusetts, the museum houses one of the oldest ongoing collections of Native American art in the country and continues to acquire important historic works in addition to work by contemporary Native American artists. Drawing primarily on North American sources, the more than seventy featured pieces include beadwork, textiles, ceramics, sculptures, and paintings that represent such diverse groups and regions as the Penobscot in the Northeast and Haida of the Pacific Northwest Coast, to the Pueblos of the American Southwest and Incas of Peru. The works reveal the complex connections between the traditional and the personal, the present and the past, the Native and the outsider (Figs. 1, 2).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Djilakons figurine, Kaigani Haida artist, Village of Kasaan, Southeastern Alaska, circa 1830. Wood, human hair, bone, shell, nettle fiber, paint. H. 4, D. 17-1/8, W. 5 inches. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; ex-ABCFM collection, 1976, E53452. Photography by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey Dykes.

|

These two works represent Djilakons, the noble ancestress of the Eagle clan of the Kaigani Haida tribe of Southeastern Alaska. Prior to European contact, no such masks or figurines were known to exist in Haida communities, and the mask lacks any evidence of having been used in ceremony or dance, indicating that they were likely made for the tourist market. No doubt both were created by the same Kaigani Haida artist, and were among fourteen known works collected between 1820 and 1840 during the sea otter fur trade. That the mask and figurine represent Djilakons is indicated by the typical symbols used to represent her: the red design on the right side of the nose and cheek, the blue design adorning the forehead, the solid red edging on the face that extends from temple to chin, and the labret, a protruding lip ornament. In early nineteenth-century Alaskan communities, labrets were markers of high social status and beauty. Mariners and missionaries found labrets at once fascinating and repugnant, which can, in part, account for their appearance in early souvenir and trade items as well as for their disappearance by the late nineteenth century.1

|

|

|

|

|

Metaphor & Identity

|

|

|

Metaphor and Identity presents works shaped by the narratives of the natural and supernatural worlds that influence personal and cultural identities. To Western sensibilities, Native American works may seem merely functional, but in fact they are endowed with layers of cultural and personal meaning. While every work of Native American art is the individual expression of its creator, it is also grounded in the values of the artist's community and culture (Figs. 3, 4).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Iyokopa (baby carrier), Dakota artist, Great Plains, circa 1840. Wood, leather, porcupine quills, metal, dye. H. 17, W. 33, D. 15 in. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; museum purchase, 2002, E27984. Photography by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey Dykes.

|

Native art is frequently created to honor an individual as they undertake a new role in the community. In a Dakota family, a new or expectant mother was sometimes given the gift of an iyokopa (baby carrier or cradleboard), either newly made or an heirloom. Used during an infant's first year of life, it facilitated transport and offered security for the infant while freeing the mother's arms for chores. This spectacular example of Dakota quillwork is one of three similar extant baby carriers, all made before 1840. Large fields of white quillwork with orange and black geometric and humanistic designs boldly decorate the main wrapping. The carrying strap and hanging metal cone strips feature brown and black motifs depicting Thunderbird (also called the Thunderer), an omnipotent spirit-being who uses lightning and bad weather to keep dangerous Underworld creatures at bay. Thunderbird can also bestow blessings on humans, and the depiction on this cradleboard can be understood as a request to protect the baby and deflect harm. Given the quantity of metal cones used on this carrier, the tremendous feat involved in processing the thousands of porcupine quills, and the weaving of such an elaborate and meaningful design, it is likely that it was made for a family of very high rank.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Crow Dance, Rick Bartow, Wiyot (b. 1946), Oregon, 1990. Mixed media on paper. 26 x 20 inches. Courtesy Peabody Essex Museum; gift of Mr. and Mrs. James N. Krebs, 2004, E302343. Photography by Jeffrey Dykes.

|

Contemporary artists still reference their cultures' metaphoric forms and images while expanding their formal vocabulary and exploring issues of personal identity. Rick Bartow is an expressionistic artist whose work often emphasizes connections between his past and present and between animal and spirit worlds. Here a crow is transforming into a human -- or perhaps a human is blending with the crow spirit. The figure's ribs are visible and its arms are outspread in an almost Christ-like pose. The figure separates the field into quadrants of bold color, fringe-like dashes and dots, and empty space. Bartow's transformational images began to emerge in his work during a cathartic period in his life when he was getting sober. Bartow has explained his artistic process, "Drawing comes from inside my head, down my arm, to my hand. As the work begins to intensify, there is little of importance below the armpits. My legs carry me back and forth in front of the drawing. Occasionally, I blindly run into objects, cussing and moving on from the shock of the collision. The marks become little dictators. They demand my attention and sometimes, even my blood as fingers crack and bleed." (For Bartow’s full statement see www.froelickgallery.com.)

|

|

|

|

Continuity & Innovation

|

|

|

Continuity and Innovation illuminates the nurturing dialogue between tradition and innovation. From its beginnings, Native American art has reflected a continuous evolution of design and use of media. Works deeply rooted in specific artistic traditions have regularly shown evidence of stylistic, aesthetic, and cultural borrowing and innovation (Figs. 5, 6).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Overcoat, Aleut artist (Alutiiq or Unangan), Aleutian archipelago, circa 1824–1827. Alaska. Sea lion intestine, dyed esophagus, seagrass. 55-7/8 x 45 inches. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; gift of Seth Barker, 1835, E7344. Photography by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey Dykes.

|

Throughout the Aleutian Islands, Kodiak Island, and the nearby Alaskan mainland, the intestine or "gut," of seals, sea lions, whales, walrus, and bears was used in the manufacture of durable, entirely waterproof material for rain gear. Native women used strips of gut to make hunting anoraks and bags, often decorated with strips of bird or sea-lion esophagus, tufts of wool, or sparse fringe. The quantity of decoration was an indication of the owner's status as well as his wife's devotion and skill. While fancy capes and long parkas may have originally served a ceremonial purpose, they later came to be more commonly used as presentation pieces. This overcoat, made from sea lion intestine and decorated with stunning bands of appliquéd strips of dyed esophagus, is influenced by European clothing, specifically a high-collared Russian officer’s overcoat. Called kamleika by the Russians, such waterproof coats may have originally been commissioned by Russian and American fur traders and military officials as souvenirs and gifts.2

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Basket, Barbara Francis, Penobscot (birthdate unknown), Old Town, Maine, 2005. Ash and sweet grass. H. 9-3/4, D. 11 inches. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; gift of Merry Glosband, 2005, E302704. Photography by Dennis Helmar.

|

Today's Native American artists live and work in varied cultural and artistic worlds while remaining actively connected to their traditions and communities. Born and raised on Indian Island, Maine, Barbara Francis learned to make baskets from her grandmother and other elders. Penobscot and other Native American Maine-based artists have sold decorative and utilitarian baskets to tourists, visitors, and local farmers for more than 200 years. Recently, Francis began selling her work at the annual Santa Fe Indian market that has traditionally focused on Southwest artists. Here, Francis extends the tradition of fancy baskets -- elaborately woven baskets that became popular in the Victorian era -- by enlarging the form. In a conversation with the author of this article Barbara explained, "Basketmaking is a tradition that my ancestors left for me to follow... This basket was a work of love. I wanted something very special -- an old look with a new twist. The preparation of the materials was done by my husband, Martin. This basket would be the last project we undertook together. Martin passed away on January 1, 2006."

|

|

|

|

Icons & Politics

|

|

|

Icons and Politics addresses the question of what it means to be Native American. Outsiders have traditionally portrayed Native American people according to prevailing ideologies. Thus popular notions of "being Indian" have evolved through perceptions of Native American artwork, lacking its original communal, ceremonial, or functional contexts (Figs. 7, 8).

|

|

|

|

|

|

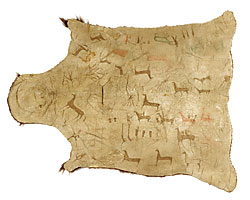

Fig. 7: Buffalo robe, Northwestern Plains artist, circa 1850–1875. Buffalo hide, paint. 86 x 94-1/4 inches. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; gift of Stephen Wheatland, Augustus P. Loring, Thomas Barbour, and Lawrence Jenkins, 1945, E24991. Photography by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey Dykes.

|

For hundreds of years, robes made of buffalo hide were a major pictorial medium for western Native artists, documenting important battles, personal exploits, and visionary experiences. The robes were worn wrapped lengthwise around the body, and the painted designs were visible in cold weather when the fur was turned to the inside. In the second half of the nineteenth century, buffalo were practically extinct, having been over-hunted for their hides. Despite this decline, buffalo and their hides, along with feather headdresses and fringed, beaded clothing became generic Native American symbols in twentieth-century popular culture.

Stylistically, the robe appears to have originated in the Northwestern Plains during the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Tethered horses near a teepee frame; a group of men shooting from an enclosure; and a man wrestling with a bear are among the painted vignettes. Also visible are guns, crooked staffs, a buffalo, and an elk. The coat was discovered in Salem, Massachusetts, in the late nineteenth century. It was used for many years as a carriage robe by the Sanders family, with the painted surface hidden by an attached cloth lining. The painted designs were discovered when the lining disintegrated.3

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Pueblo Feast Day, David Bradley, White Earth Ojibwe (b. 1954). Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1997. Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 60 inches. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; gift of Mr. and Mrs. James N. Krebs, 2001, E301824. Photography by Jeffrey Dykes.

|

Many contemporary Native American artists subvert popular stereotypes to present a complex world where tourism, mass media, myth, marketing, politics, and the traditional intersect. In this painting, David Bradley imagines a Pueblo family's feast day table. Southwestern Pueblo communities host feast day celebrations to honor patron saints and they perform dances to maintain harmony with the spirit and natural worlds. The public is generally welcome at these dances and sometimes invited into private homes to share food. The guests at Bradley's table include a scientist from nearby Los Alamos, a scantily clad woman and her poodle, a Navajo mother and her baby, and the Lone Ranger. The view through the window shows a casino in the distance and tourist traffic along the highway, and in the foreground, President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton with Secret Service agents, along with the famed Southwestern artist Georgia O'Keeffe, and the Lone Ranger's sidekick, Tonto. Pueblo Feast Day offers a wry commentary on intercultural exchange and the challenges of living a dual existence (both traditional and modern) in a changing world. Bradley's mix of star-studded visitors and mythic icons is an observation on how this time-honored -- and now commercialized -- feast day tradition is at once sacred and profane. •

|

Intersections, Native American Art in a New Light is funded in part by ECHO (Education through Cultural and Historical Organizations), which is administered by the US Department of Education, Office of Innovation and Improvement. The exhibition will remain on view indefinitely.

|

Karen Kramer is the assistant curator of Native American art at the Peabody Esssex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. She co-curated Intersections, Native American Art in a New Light with guest curator Laurie Beth Kalb.

|

|

|

|

1. Peter Macnair and Jay Stewart in Uncommon Legacies: Native American Art from the Peabody Essex Museum, John R. Grimes, Christian Feest, and Mary Lou Curran (American Federation of Arts, New York, and University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2002), 133, 150.

2. Uncommon Legacies, 166.

3. Ibid, 206.

|

|

|

Download the Complete Article in PDF Format Download the Complete Article in PDF Format     Get Adobe Acrobat Reader Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

|

|

|

|

|

|

|