Paris & the Countryside: Modern Life in Late-19th-Century France

This archive article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Late-nineteenth-century France was witness to unprecedented social, economic, and technological change. In 1853, with the appointment of Baron Georges Haussmann as prefect by Napoleon III, Paris was transformed from a medieval city into a modern one. Under Haussmann’s ruthless guidance, entire neighborhoods were demolished to create the wide boulevards, parks, squares, and quays of today, along with new office buildings and housing. Concurrently, France’s transportation infrastructure improved dramatically, with railway lines and roads connecting Paris to once remote communities and coastal towns. Easier access to Paris, the nation’s dominant commercial and cultural center, and the rise of new industries in its suburbs led to the rapid influx of people from the countryside, doubling the city’s population. The rural landscape and culture changed too, with industry and tourism infiltrating rural villages.

In his 1863 essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” poet and critic Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) called on artists to paint modern life. This was a radical concept, for until then contemporary life had not been considered a subject worthy of fine art. Many artists heeded his call. Some celebrated the new—trains, coastal holidays, fashion, shopping, and the burgeoning entertainment industry—while others focused on the negative—pollution, homelessness, and poverty. Still others demonstrated their sense of modernity through their style and techniques rather than their choice of subject.

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

The laundress and her companion in misery, the ironess, were extremely popular subjects in the 1890s. Carrying heavy bundles of clothes through the streets of Paris, or mired in urban sweatshops, they were the visual personification of poverty for many artists. Degas poignantly captures the dehumanization of such workers in this painting, in which the identity of the woman ironing is literally masked, both by her down-turned gaze and by the laundry she has ironed.

Jean-Louis Forain (1852–1931)

Like Edgar Degas, Jean-Louis Forain frequently depicted ballerinas, either singly or in groups, during their classes. Whether the dance milieu was also one that encouraged prostitution is debatable. As treated by Degas, ballet classes, made up of young girls, often poor and willing to do anything to continue their training, were a place where prostitution might flourish. Forain often portrayed young girls in languorous poses, stretching their limbs, frequently in the company of unsavory-looking older men. Here, an older man, of obvious wealth, stands behind the young ballerina he is trying to seduce.

Louis Abbéma (1858–1927)

In this painting, Abbéma answers Baudelaire’s call to paint modern life, showing leisure time at Tréport, a fashionable summer resort for Parisians on the Normandy coast. Croquet was au currant, enjoying a resurgence in popularity in France at the time. The ability to go out alone in unadulterated nature and to record one’s sensations on the spot, a hallmark of Impressionist painting, was not one accorded to women. Here Abbéma does manage to paint en plein air, but in a setting where women out-of-doors were properly escorted. Abbéma studied with several artists, including Carolus-Duran, and at the age of eighteen found success with her portrait of Sarah Bernhardt. She exhibited regularly at the Salon of French Artists. She also painted panels and murals for the Paris Town Hall, the Paris Opera House, and numerous theaters.

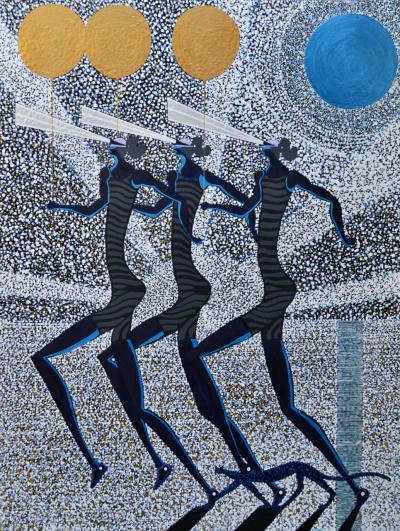

Georges Seurat (1859–1891)

This study for Le Chahut is almost identical to the final version now at the Kroller-Muller Museum in Otterloo, the Netherlands, which was Seurat’s last major work. “Chahut” is another name for the cancan, which derived from another popular dance, the galop. Until the 1890s, when it moved to music halls, the chahut was danced by both sexes rather than by a chorus line of females employing suggestive high kicks. In the mid-1880s, Seurat developed the style of painting known as pointillism or divisionism that looked to then-contemporary scientific, optical, and psychological theories to create luminous works.

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

The town of Lavacourt on the Seine was located on the opposite bank of the river from Vétheuil, where Monet lived from 1878 to 1881. During this time Monet would often go out on his boat to paint. One of his favorite spots to work in his studio boat gave him a view of the town of Lavacourt. In paintings such as this, Monet made clear his preference for the unadulterated natural world over the manmade world burgeoning in the cities and encroaching into parts of the countryside during this time. It is evident from historical texts that the conscious escape from modern life that Monet’s paintings provided was appreciated by at least some of those who owned and saw them, a sentiment shared by many viewers today.

James-Jacques-Joseph Tissot (1836–1902)

One of the key paintings in Tissot’s Parisian Woman series, this work emphasizes the way in which women were seen as objects for display. Here a fashionable woman hangs on the arm of a much older man, implying that, despite his age, he is still capable of attracting young women. The male figure is using the élégante to enhance his position, since his male peers all turn to look at the stunning individual at his side. Tissot sets up a sensationalized visual narrative capable of holding the attention of a viewer much as it would in a newspaper article, gossip column, or serialized story.

Jean-Baptiste-Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927)

Exhibited at the Impressionist’s 1877 exhibition, this painting records the impact of the railroad on the landscape. Here Guillaumin, who began painting while he was employed by the Paris-Orléans railway, depicts the intersection of two newly built structures—the Paris-Sceaux railway line and the Aqueduc de la Vanne. Once a popular location for country houses owned by wealthy Parisians, with the introduction of the railroad in the 1840s, Arceuil became a tourist destination. The attire of some of the women suggests that they have come from the city.

Paris and the Countryside: Modern Life in Late-19th-Century France was an exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art June 23 through October 15, 2006. It offered a cross-section of approaches to being a painter in, and of, the modern world in the late nineteenth century. The exhibition, exclusive to this venue, was accompanied by a 136-page, full-color catalogue, with essays by Dr. Gabriel P. Weisberg and Dr. Jennifer L. Shaw. For information call 207.775.6148 or visit www.portlandmuseum.org.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2006 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

-----

Carrie Haslett is the Joan Whitney Payson Curator at the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine, and organizer of the exhibition.