|

|

|

|

by Sumpter Priddy

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Child's Windsor rocking chair, Virginia, probably Abingdon, ca. 1825. Yellow pine, poplar, maple, hickory and painted and transfer-printed decoration. H. 17, W. 10, D. 19 in. Courtesy of Roddy and Sally Moore; photography by Gavin Ashworth. |

Collectors and curators alike have long been drawn to the colorful household furnishings of the early Republic. These decorative objects were the products of creative Americans who worked in diverse environments—large-scale urban cabinet shops, smaller traditional rural shops, homes, and schools. Over the last century, scholars have usually studied and grouped the resulting goods on the basis of a perceived level of expertise of the makers, viewing some as sophisticated and academically informed, some as natural expressions of untutored genius, and others as the charming work of young academicians (Fig. 1). In contrast to our modern perceptions, Americans of the period spanning the 1790s to 1840 unified these seemingly diverse goods with the descriptive term "Fancy."

Fancy was intimately linked to the experimentalism and inspirational ideals that followed the Revolutionary War. A survey of the word and its related concepts in period literature and philosophy, and in artisans’ accounts and advertisements, reveal its influence upon a broad range of artistic expressions. Fancy came to signify almost any activity or object that delighted the human spirit—it occupied people’s minds, pervaded their homes, and shaped their perspectives on the world. Just about anything that pleased the senses—from music and dance to horticulture—fell within Fancy’s realm. Household furnishings held an important role in conveying this vibrant character and disseminating the concept of Fancy through a new approach to ornament.

Consideration of Fancy's impact causes a significant reappraisal of the intellectual awareness of Americans in this country's early years and of the colorful and emotionally engaging products of the period. Fancy ornament made implicit connections to people, things, and ideas that transcended the objects themselves. Rather than naïve expressions, they reflected a progressive Romantic outlook that centered on absorption and response, allusion and association.

|

Consumers, artisans, and shopkeepers alike used the term Fancy to define a wide range of engaging objects. Formal painted furniture was advertised as Fancy; Fancy painting referred to the art of imitative graining applied to furniture and architectural interiors to suggest stunning woods and marbles (Fig. 2); Fancy weaving identified eye-popping overshot coverlets; and Fancy glass defined whimsical, free-form glass figures. Americans also advocated Fancy cooking, Fancy music, and Fancy literature, as a means to convey their belief in the new-found expressive concept.

Fancy style reflected an innovative philosophy that valued imagination and creativity, and acknowledged the importance of day-to-day experience in helping to shape personality and character. The concept, in part, grew out of attempts by the preceding century’s leading thinkers to decipher and fuel the human mind. Numerous individuals contributed to the emergemce and acceptance of Fancy, from the philosopher Joseph Addison at the beginning of the eighteenth century, to educators such as Dugald Stewart, at the end. These men hoped to refine the senses and thereby nurture the intellect and the memory. Their writings often emphasized how objects and experiences could employ such intellectual stimulants as novelty, variety, and wit to catch the eye. Integral to the phenomena of Fancy, viewers expected to have strong emotional responses to engaging experiences—particularly the visceral surprise, delight, whim, and caprice that accompanied the first impression upon the mind.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Chest with drawers, North Carolina, 1780– 1810, painted ca. 1830. Poplar, yellow pine, brass, iron, and later painted decoration. H. 30, W. 491/2, D. 223/4 in. Courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Robert F. White; photography by Gavin Ashworth.

|

|

These intangible fleeting responses helped to define the attributes of the new Fancy style, which provided an alternative to the restrained classical taste, and were personal and more conceptual in nature. Similarly, Fancy’s appearance was defined by the impact of light, color, and visual motion, characteristics of objects that are also elusive and difficult to quantify (Fig. 3). These six ephemeral traits—novelty, variety, wit, light, color, and motion—defined the essential building blocks of the Fancy style; for Americans, they bore no less weight than a pointed arch did in signifying the gothic style, or a classical column in suggesting Roman design. By applying the word Fancy to engaging artifacts, Americans conveyed a value placed on the ephemeral pleasures of life.

American artisans created an astonishing range of Fancy goods to feed the public’s clamor for the engaging new style. A rum jug (Fig. 4) made in New York State in about 1825 reflects the complex layers of meaning that often embody the boldest expressions of the Fancy aesthetic. It sports two faces of the devil—one, grotesquely human, facing to the right; and the other, representing Beelzebub, with devilish goat-like features, gazing to the left. The faces are linked in the center by their shared horns and a shared eye—and by their whimsical symbolism for the “demon rum” inside the jug. Fancy objects such as this create a complex maze of illusion and allusion in which the imagination can freely wander.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Cup and Saucer, England, 1830–1840. Earthenware and polychrome decoration. Diam. 45/8 in. (saucer); H. 17/8, Diam. 3 in. (cup). Private Collection; photography by Gavin Ashworth.

|

Americans' fascination with the Fancy style received a significant boost with the introduction of the kaleidoscope (Fig. 5). This device, invented in 1816 by British physicist David Brewster, gave imagination the perfect new tool to "Fancy to itself things more great, strange, beautiful than the eye ever saw." Over 200,000 kaleidescopes sold in a three-month period, and by 1822, a British visitor to the United States found that they were manufactured "in quantities so great? that they were given "as a plaything to children." 2

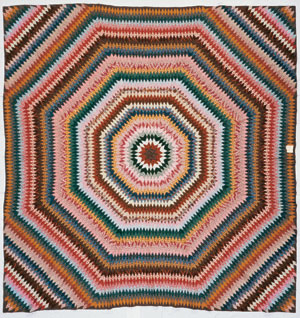

Brewster recognized the kaleidoscopes potential influence on design, and in 1819 he published A Treatise on the Kaleidoscope, with an influential chapter "On the Application of the Kaleidoscope to the Fine and Useful Arts." It is likely that he never anticipated the extent of his invention's astonishing impact in America, where many individuals eagerly sought to distance themselves from traditional European classical taste. Here, the crisp geometric patterns introduced by the kaleidoscope were emulated on an array of household goods, particularly quilts (Fig. 6).

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Chest with drawer, Rhode Island, ca. 1830. Pine and painted decoration. H. 377/8, W. 453/4, D. 191/4 in. Private collection; photography by Gavin Ashworth.

|

|

In a world where art previously had been shaped by classical prototypes, or by attempts to emulate the splendors of nature, the kaleidoscope extended notions of beauty into unprecedented realms. By using a kaleidoscope as inspiration, an artisan could transform a traditional object into something extraordinary. A quilt with a radiating star or furniture painted with an explosion of color (Fig. 7) differed significantly from an object ornamented with details borrowed from antiquity or drawn from nature. Kaleidoscopic ornament represented the product of an unprecedented design process, the unique perspective of the individual who experienced it, and of the distinctly personal emotions generated by the moment.

|

|

|

|

|

| Fig. 4: Jug, New York, ca. 1825. Salt-glaze stoneware with incised and cobalt decoration. H. 15 1/4 in. Courtesy of Elbert H. Parsons Jr.; photography by Gavin Ashworth. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

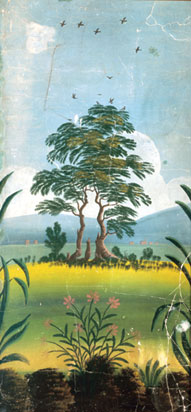

Fig. 8: Landscape mural with soldier silhouette between trees, by Rufus Porter, 1838, Dr. Francis Howe House, Westwood, Mass. Paint on plaster on chestnut lath. 60 x 30 in. Courtesy of Donald Heller and Kimberly Washam. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: View into a simple kaleidoscope with two mirrors. Silvered and colored glass.

Photograph by Hans Lorenz. |

Few individuals better captured the spirit of Fancy’s phenomenon than the New England artist, inventor, and ornamental painter Rufus Porter (1792–1884). The founder of Scientific American and author of a popular booklet entitled Curious Arts, Porter was an educator who provided the public with instructions for fashioning a wide array of decorative household Fancy goods—transparent window shades, painted floorcloths, and grained or painted murals (Fig. 8), to name a few. He also popularized a recipe for making “exhilarating gas,” a period term for nitrous oxide or laughing gas. While this bit of chemistry may seem a far cry from his other eye-catching material goods, like many of his contemporaries, Porter was not just interested in the appearance of Fancy objects. He also was intrigued by their psychological and physiological impact. In presenting his readers with the laughing gas recipe, Porter provided an explanation that applies equally well to Fancy decorations:

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Quilt by Rebecca Scattergood Savery, Philadelphia, ca. 1827. Cotton chintz. 128 x 132 in. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

Museum purchase with funds provided by the estate of Mrs. Samuel Pettit and additional funds by Mr. Pettit in memory of his wife.

|

|

The effects…are in general, highly pleasurable, and resemble those attendant on the agreeable period of intoxication. Exquisite sensations of pleasure; an irresistible propensity to laughter; a rapid flow of vivid ideas;…are the ordinary feelings produced by it. And what is exceedingly remarkable, is, that the intoxication thus produced, instead of being succeeded by the debility subsequent to intoxication by ardent spirits, does, on the contrary, render the person who takes it, cheerful and high spirited for the remainder of the day.4

During the age of American Fancy, Americans saw artistic expressions and imagination as essential to the development of the mind and character. At the same time, they embraced a cultural phenomenon that coalesced into a vision and style with far-reaching implications. Fancy was a concept that helped to define the early republic in unprecedented ways, and no term better captures its spirit. Understanding that fascination opens up an entirely new view of nineteenth-century America and its material goods—an awareness that rekindles the long-forgotten perspective in which objects and experiences are tied inextricably to the imagination of their creators and to the delight and response of their beholders.

Sumpter Priddy owns a gallery in Alexandria, VA. He is author of American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Chipstone, 2004) and is guest curator of the accompanying exhibition.

|

|

1 Joseph Addison, "Pleasures of The Imagination," The Spectator (June 2, 1712).

2 James Flint, Letters from America, containing Observations on the Climate

and Agriculture of the Western States (Edinburgh: W. & C. Tart, 1822), 20.

3 Sir David Brewster, A Treatise on the Kaleidoscope (Edinburgh: Archibald

Constable, and Co., 1819).

4 Rufus Porter, A Select Collection of Valuable and Curious Arts, 2d ed.

(Concord, N.H.: J. B. Moore, 1826), 100.

|

|

|

|