|

| Home | Articles | Curator's Choice: The Peabody Essex Museum and the Sea |

|

|

|

by Daniel Finamore

|

|

|

Fig. 1: USS Constitution vase, Pierre Louis Dagoty, Paris, 1817. Porcelain, marble, enamel. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes. M27413.1-2.

|

The Peabody Essex Museum has been collecting maritime art and objects from America, Europe, and around the world for over 200 years. Today, the museum holds a rich collection of paintings and prints, as well as ship models, navigational instruments, scrimshaw, and other objects reflecting life at sea (Fig. 1). The museum's maritime art and history installations are now housed both in the new 2003 galleries designed by Moshe Safdie and in the renovated East India Marine Hall galleries built in 1825. Return visitors to the museum will immediately notice a fresh approach to the collections, which emphasizes art and objects that exhibit the distinctive media and motifs used by those who discovered artistic inspiration from the sea and recognized it as a force for cross-cultural vitality. Both galleries feature some of the signature holdings of the museum and artifacts that have rarely, if ever before, been exhibited.

Art and objects that reflect the maritime experience regularly emphasize adventure, technical challenges, exposure to different ways of life, and the social distinctiveness of those who spend long periods at sea. Whether documenting individual experience or striving for more universal symbolic representation, maritime subject matter evokes the adventure, risk, and potential rewards of seafaring. The initial gallery dedicated to maritime art presents a selection of works that transcend the specific narrative of an individual ship. In Icebound Ship (Fig. 2), William Bradford explores themes of universal significance, such as the vastness of the natural world and the vulnerable place of humanity within it.

|

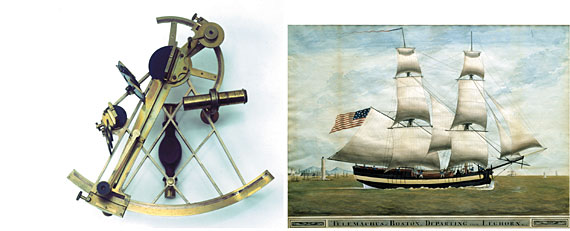

Further explored in the maritime art installations are the materials, techniques, and visual vocabulary adopted by artists working on ships or in port towns. Many of these artists, often self-taught, created objects that gave expression to personal and community experiences. Scrimshaw, for example, is made of materials available to whalemen, and often illustrates topics of interest to men who lived on board whaleships for years at a time (Fig. 3). Other objects incorporate ropework or stitching, essential skills of the career mariner. The challenge of working the seas has also inspired an array of specialized tools and techniques to maximize efficiency and minimize risk (Fig. 4). Shipbuilders, navigators, and inventors often infused their instruments, models, charts, and plans with decorative refinements to convey their symbolic importance to the maritime endeavor.

|

|

|

Fig. 2 (above): Icebound Ship, William Bradford (1823-1892), New York City, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes. M27190.

|

|

|

Fig. 3 (left): Scrimshaw of Brigantine Chinchilla and Brig Tahmaahmah, Edward Burdett (1805-1853), ca. 1825. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes.

|

For the connoisseur, a gallery dedicated to ship portraiture presents the most specialized genre of maritime art in a setting that fosters careful inspection and comparison between artists and schools. These paintings celebrate their intended vessels, carefully placing them within constructed compositions and in specific situations, often with nautical and cultural accuracy (Fig. 5). A great deal of maritime art possesses underlying themes that commemorate the achievements of people and nations, but may not be as detail-oriented in regard to the ships (Fig. 1).

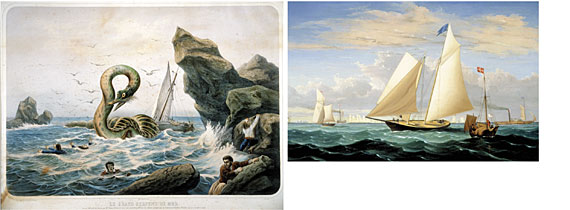

While many works made at sea celebrate personal experiences, acting as mementos of distant lands and important experiences, a large component of contemporary marine art addresses nostalgic themes, focusing on the seafaring life of previous times. Whether employing a retrospective or contemporary view, the most powerful of these images contributes to the iconography of a national identity (Fig. 6).

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4 (above left): E. Hoppe's Improved Sextant, London, England, 1804. Brass, glass, silver, wood. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes. Museum purchase with funds from the David P. Wheatland Charitable Trust. M27480. Fig. 5 (above right): Telemachus of Boston--Departing from Leghorn, Guiseppi Fedi (active 1792-1819), Livorno (Leghorn), Italy, ca. 1805. Watercolor. Gift of Mr. Alexander O. Vietor, 1981. M18651. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes. Fig. 6 (below right): The Yacht America Winning the International Race, Fitz Hugh Lane (1804-1865), Gloucester, Mass., 1851. Oil on canvas. Gift of Augustus P. Loring, Jr. M04696. Courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes. Fig. 7 (below left): Le Grand Serpent de Mer, Paris, France, mid-19th century. Colored lithograph. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum; photography by Sexton/Dykes. M09341.

|

Both the sea and seafaring figure prominently in the cultural identities of Europe and America. The last group of galleries offer an opportunity for closer examination of the cultural underpinnings behind much of this art associated with the sea. Between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries, global voyages by Europeans raised great public curiosity about the places and people they encountered. Images of the world beyond were enormously popular, no matter how inaccurate or contrived (Fig. 7). Images of mass popular appeal often emphasize adventure, whether marvelous or tragic. Partly romantic, partly terrifying, boldly contrived illustrations such as those used to embellish novels or for naval recruitment have defined seafaring for the majority of people with no personal experience of it.

Maritime arts traditionally reflect the influence of seafaring life on those who created, commissioned, and collected it. Visitors to the new maritime art and history galleries will discover the finest examples of their type in an environment that stimulates examination, comparison, and analysis.

|

Daniel Finamore is Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

|

|

|

|