|

|

|

|

|

by Deborah Harding

|

OUR NATIONAL BIRD, the American bald eagle, took flight in popular culture and decorative arts in the earliest days of the young Republic, enjoying a profusion of interpretations in the hands of idealistic American folk artists. As noted by Paul D'Ambrosio, Chief Curator of the New York State Historical Society, "American folk artists looked to the values and ideals of the new nation to provide an identity larger than themselves or their communities. These artists absorbed the popular symbols of the day--most notably the bald eagle--and remade them into personalized expressions of a collective consciousness." Though many of these craftsmen are unknown to us today, their accomplishments are recognized by collectors and connoisseurs for their artistic appeal and patriotic message.

The image of the eagle, as represented in our country’s visual vocabulary, evolved over time. As our democratic and artistic heritage are tightly interwoven, we can better appreciate the interpretation of this patriotic symbol by understanding the context in which it developed.

|

|

|

Fig. 1: 1885 Tiffany and Company Great Seal. Photography courtesy of the Department of the Army, Institute of Heraldry.

|

Inspiration: The Great Seal

When the United States won its independence from England, it was important to establish a visual vocabulary to represent its new status. Topping the list of post-Revolutionary official emblems was the need for a national coat of arms that would appear on a seal which would be used to authenticate the president’s signature on treaties and other official documents.

On the evening of July 4, 1776, the day the Declaration of Independence was adopted, the Second Continental Congress appointed Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson to develop an appropriate design for use as the official seal for the new nation. No one could have predicted that the process would take six years to complete.

|

The design recommended by Franklin's committee was rejected, as were those of two subsequent committees. The Secretary of Congress, Charles Thomson, finally settled the issue by incorporating elements from each proposal and adding a few of his own. From the Franklin committee he chose the motto "E Pluribus Unum" (Out of Many, One); from the committee headed by James Lovell of Massachusetts in 1780, the olive branch signifying peace and a constellation of thirteen stars (influenced by the 1777 flag design); and--most significant--from the 1782 proposal, an eagle, introduced into the mix by author and heraldry scholar William Barton.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Village Hotel sign, artist unknown, South Hadley, Mass., ca. 1825–1830. Painted wood. 36 x 56 inches. Courtesy of Kendra and Allan Daniel; photography by Helga Photo Studio. This two-sided sign originally hung at Salathiel Judd’s village hotel, which operated as a temperance house until 1840.

|

Thomson chose the American bald eagle1 as the central motif and positioned a shield on its breast. He placed an upright bundle of arrows (representing war power) in one talon, and an olive branch (representing peace) in the other. He added thirteen stars surrounded by clouds in a crest (above the shield) and a scroll that read "E Pluribus Unum" in the eagle's beak. After some fine-tuning by Barton, Congress adopted this design for the Great Seal on June 20, 1782.2

|

|

|

|

|

Declaration of Independence eagle, artist unknown, New England, ca. 1825–1840. Oil on wood, 20 x 24 in. Courtesy of Peter Tillou; photography by Geoffrey Gross. This magnificent eagle may have been the work of an ornamental sign painter made as a decorative plaque for a business establishment.

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Fire buckets owned by Nathaniel Thayer Moulton, artist unknown, Portsmouth, N.H., ca. 1813. Painted and hand-sewn leather. H. 13-1/2 in. Courtesy Northeast Auctions; photography by Luigi Pelletieri.

|

As seals wore out, new dies were periodically cut and variations made. In 1885, Tiffany & Company cut the pattern that remains in use today (Fig. 1). Tiffany's changes made the eagle a bit more realistic: the original bent-knee frog-like legs were extended and feathered. In addition, the glory (clouds) in the crest became a contained circle, the number of arrows reverted from six (a change made in 1841) back to the original thirteen, and the olives (also added in 1841) on the olive branch were increased to thirteen.

Citizens of the new Republic were quick to incorporate the eagle into their artistic or business endeavors. Eagle motifs were proudly represented on everything from parade banners to schoolgirl embroideries. Weathervanes, figureheads, coverlets, calligraphic drawings, fire buckets, pottery, store and tavern signs, furnishings, quilts, and hearth rugs all displayed our national symbol.

Recurring eagle and shield symbology from the Great Seal of the United States are enduring, recognizable expressions of freedom in all mediums of American folk art.

Signboards

Hand-painted signs were a familiar sight in America as early as the mid-seventeenth century, when court orders required tavern owners to prominently display an identifying sign. Before the Revolution, tavern owners--influenced by their British counterparts--favored lions, bulls, swans, and unicorns. After the Revolution, our newly designated emblem of independence--the American bald eagle--replaced many of the British motifs, and lions were quickly painted over with spread-winged eagles (Fig. 2).

|

|

|

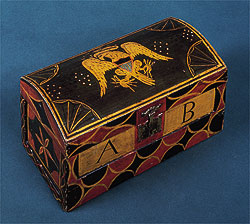

Fig. 5: Paint-decorated trinket box, artist unknown. Probably Albany County, New York, ca. 1805–1820. Painted basswood. H. 6-1/4, W. 11-3/4, D. 6-3/8 in. Private Collection. Courtesy David A. Schorsch and American Hurrah Archive.

|

Banners

In the nineteenth century, banners were an integral part of every parade. Conveying support or protest for a cause or a candidate, and figuring prominently on military banners, eagles were painted in oil on sailcloth, canvas, or sometimes even on silk or satin. The banner in figure 3 is a good illustration for this purpose, celebrating the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. The scene expresses the Whig belief that the development of coastal and internal transportation and the protection of home and industries were vital to the growing Republic.

Firehouse Folk Art

With the formation of fire societies in the early nineteenth century, volunteer fire fighters as well as homeowners and shopkeepers were required to own leather fire buckets—usually hung under the stairs or near the door so as to be quickly accessible at the sound of alarm. After use during a fire, buckets had to be reclaimed by their owners and therefore, some form of identification was necessary. This task was generally undertaken by ornamental painters, who often used eagle-and-shield devices on buckets (Fig. 4) as well as on other fire society paint-decorated items. These elaborately painted hats, capes, banners, engine panels, and hose cart panels were commissioned for parades and other ceremonial occasions. Fire companies competed with one another for the most spectacular paraphernalia and considerable sums of money were spent for prizewinning designs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Whig political banner, painted by Terrance J. Kennedy, Fleming and Auburn, New York, ca. 1840. Oil on canvas. Diam.: 66 in. Courtesy of the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York; photography by Richard Walker.

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Stenciled stoneware crock, inscribed T. F. Reppert Eagle Pottery Co., Greensboro, Pa., ca. 1885. Salt-glazed stoneware with stenciled cobalt decoration. H. 21, Diam. 12 in. Courtesy Skinner, Boston and Bolton, Mass.

|

Painted Furnishings

A variety of eagle embellishments are found on formal Federal furniture, but fewer folk art interpretations were painted or inlaid on utilitarian home furnishings. One of the more popular objects usually decorated were boxes (Fig. 5). Especially prevalent in New England and Pennsylvania, small boxes were used for storing everything from candles to silverware, important documents and sewing supplies. Lids and front panels were embellished by schoolgirls and decorative painters alike.

Pottery

Tavern signs, banners, firehouse objects, and painted furniture were often the work of ornamental painters. Public- spirited renderings also decorated jugs, jars, pitchers, plates, and crocks in the form of scratched designs on Pennsylvania's redware-based sgraffito pottery, cobalt-blue slip decorations on salt-glazed stoneware, and transfer-printed and painted ceramics exported to America from Liverpool and China. The crock in figure 6 sends a patriotic message while at the same time advertising the name of the pottery: T. F. Reppert Eagle Pottery Co.

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Eagle emblem rug, initialed P A L, Oneida County, New York, ca. 1803–1812. Yarn-sewn wool on homespun linen and burlap. 36 x 36 in. Courtesy of the Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y.; photography by Richard Walker. This rug is recorded in the Index of American Design.

|

Needlework

Ever since the time of the Revolution, Americans have proclaimed their democracy by incorporating patriotic words and images into their needlework. The eagle as it appeared on the Great Seal was soon being woven into coverlets, appliquéd onto quilts, and embroidered onto schoolgirl needlework. Times of crisis, celebration, and presidential campaigns provoked a flood of patterns and textile ephemera.

The emblematic eagle was also hooked into hearth rugs: some were of original designs while others were purchased stenciled on burlap-like backing and then individualized. PAL's rug shown in figure 7 boasts two fantasy flowers and a border of concentric circles. The eagle is portrayed in a traditional stance, but the maker used artistic expression and designed it so that the head faces the arrows rather than the olive branch (see endnote no. 2), and the shield has eleven rather than thirteen stripes. The number of stars is appropriate given that there were seventeen states when this rug was made.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Flag-bearing eagle, artist unknown, American, ca. 1876. Carved, painted, and gilded pine. H. 19-1/2, W. 32-1/2 in. Courtesy of Hyland Granby.

|

Ship Carvings and Architectural Ornaments

Ship carvers, whittlers, coppersmiths, and blacksmiths expressed national pride each in their own medium. Their handwork graced sailing vessels, advertised stores, decorated public buildings, and read the direction of the wind.

The flag-bearing, shield-carrying eagle in figure 8 is a prime example of a fine shipboard carving and bears a strong similarity to one that has been described as appearing on the door of Lincoln's presidential paddle steamer, River Queen.

|

|

|

Fig. 9: Eagle and shield weathervane, artist unidentified, Mass., ca. 1800. Cast bell metal. H. 36, W. 43-1/2, D. 4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Francis S. Andrews. 1982.6.4. Collection of the American Folk Art Museum, New York; photography by John Parnell, New York.

|

|

The tradition of weathervanes was brought to this country by New England settlers. In Europe, weather cocks frequently topped grand buildings; in America, they rested democratically on barns, stables, meeting houses, churches, public buildings, and private homes. Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, weathervanes were carved or whittled from wood, or cut from sheet metal or cast iron (not until the 1870s were the mass-produced copper variety available). Figure 9 illustrates a strikingly dramatic interpretation of the Great Seal's spread winged eagle. Bold in outline, the design successfully plays with negative and positive spaces. Although clearly an American eagle, it echoes design elements of traditional European heraldry.

Ubiquitous personifications of Great Seal iconography and other national symbols were skillfully and prolifically crafted in paint, wood, metal, and fabric by early Americans. These folk art examples create a collective visual narrative of the American spirit, hopes, and homeland. An exhibition featuring some of these images American Memory: Recalling the Past in Folk Art is on view through December 29 at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. Call 888.547.1450 or visit www.fenimoreartmuseum.org for more information.

|

This article is an adaptation from Stars and Stripes, Patriotic Motifs in American Folk Art by Deborah Harding and published by Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York. The 256-page book is available in hardcover for $75.00 from Rizzoli and the Fenimore Art Museum bookshop. ISBN: 0-8478-2485-3.

|

Deborah Harding is also the author of America's Glorious Quilts, Red & White: American Redwork Quilts and Patterns, and co-author of Home Sweet Home: The House in American Folk Art.

|

|

- Although eagles were a familiar heraldic motif in Europe as far back as Roman times, the American bald eagle was unique to North America. "Bald" is an archaic word for white referring to the bird's white head and tail feathers.

- The Presidential Seal, a variation of the Great Seal used to represent the sitting president, seems to have been first used officially on invitations and stationary during the presidency of Rutherford Hayes (1877-1881), although Presidents Polk and Fillmore are said to have designed their own versions. Until 1945, a major design difference between the Presidential Seal and the Great Seal was that the former showed the profile of an all-white eagle facing the arrows rather than the olive branch (the Great Seal eagle always faced the olive branch), leading people to mistakenly conclude that this position reflected a time when the country was at war. More likely it is simply an artistic decision. On October 24, 1945, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order for the current design (with the eagle’s profile facing the olive branch), with the addition of a wreath of stars representing the states.

|

|

|

|