|

| Home | Articles | Wallace Nutting: Antiquarian & Entrepreneur |

|

|

by Trina Evarts Bowman and Thomas Andrew Denenberg

|

In the opening decades of the twentieth century, the hectic pace of life prompted many Americans to look to the colonial past as a peaceful, more harmonious time. Although antique collecting had long been a hobby of the well to do and the United States proved to be an especially history-conscious nation in the nineteenth century, by the time the 1920s began to roar, the country was in the grip of a full-scale colonial revival.

Old homes found new lives; new houses were constructed in ancestral styles. New magazines catered to collectors of fine and decorative arts, and department stores sold reproductions to those who preferred their antiques shiny. The leading spokesman for this return to the past was a dyspeptic minister from Rockbottom, Massachusetts, by the name of Wallace Nutting (1861-1941).

|

|

|

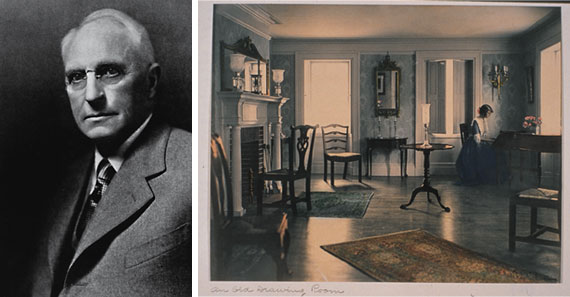

Fig. 1 (left): Portrait of Wallace Nutting from Wallace Nutting's Biography (Framingham, Mass: Old America Company, 1936), 36. Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Fig. 2 (right): Wallace Nutting, An Old Drawing Room. Hand-tinted platinum print. Courtesy of Averbach Library, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

|

Nutting, a Harvard-educated Congregational minister turned photographer, writer, antiquarian, and connoisseur, amassed an extensive collection of seventeenth-and early-eighteenth century furniture, and through a myriad of entrepreneurial activities became the public face of this consumer-based revival of colonial forms (Fig. 1).1 The minister served as the principal authority on early American furniture for much of the twentieth century. He authored more than twenty books, including Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (1921) and the encyclopedic three-volume Furniture Treasury (1928/1933). In addition to his books, Nutting published dozens of articles on colonial America and lectured to audiences throughout the United States on all that was wrong with the present and right with the past. By the time of his death in 1941, the prolific minister had played a formative role in the development of an anti-modern worldview in American culture.

Ironically, Nutting's reputation began with a nervous breakdown. Modern life literally overwhelmed him. He distrusted industrial society and, in his sermons, mourned the abandonment of rural life and traditional American values. He grew increasingly concerned with the commercialization of taste and, when he began to collect furniture, spoke out against manufacturers who produced eclectic furniture of "mongrel pattern."2 Echoing the calls for design reform by acolytes of the arts and crafts movement, Nutting harkened back to an idealized past and sought to find a place for historical forms in modern life. "The best characters are those that are built up with modern modifications out of old foundations," he wrote.3 Mentally and physically drained, Nutting retired from the Union Congregational Church in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1904 at the early age of 44. "Turned out to grass," as he liked to say, the minister turned to the popular amateur pastime of photography.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Writing arm Windsor, no. 451, Wallace Nutting, Inc., circa 1922. Pine, ash, maple. Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. The Elijah K. and Barbara A. Hubbard Decorative Arts Fund. 2000.6.1.

|

Originally a form of succor, photography soon became a means of support. In 1905 Nutting moved to Southbury, Connecticut, and perfected a technique for hand-coloring platinum prints.5 He published ever-larger catalogues of his platinotypes in 1906, 1908, 1912, and 1915, becoming one of the first and certainly one of the most successful Americans to market hand-colored photographs on a large-scale commercial basis.

|

|

|

|

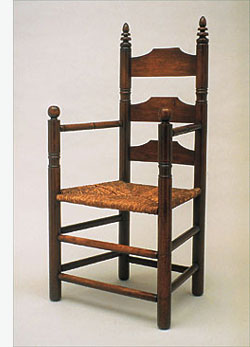

Fig. 4: Pilgrim chair, no. 493, Wallace Nutting, Inc., circa 1930. Maple. Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. The Elijah K. and Barbara A. Hubbard Decorative Arts Fund. 2001.15.1.

|

Convinced that the solution to modern problems lay in reestablishing a connection with the past, Nutting offered images of picturesque scenery seemingly untouched by modern elements, as well as interior views of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century houses complete with young women clothed in historical garb (Fig. 2). The great popularity of these latter images, which Nutting called "colonials," encouraged him to begin an interconnected series of historically minded business endeavors that promoted an idealized view of early American life and established the colonial aesthetic for the home of good taste. By depicting stately colonial homes, his images also encouraged Americans to travel about the countryside in search of the past--a pastime that Nutting soon moved to capitalize upon.

Unhappy with having to adapt to the schedules and room arrangements provided by early house museums, owned by institutions such as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Nutting assembled his very own collection of historic homes to serve as authentic backgrounds for his photographs. He purchased and restored five structures between 1914 and 1916, calling the endeavor "The Wallace Nutting Chain of Colonial Picture Houses." The chain included the Joseph Webb House in Wethersfield, Connecticut, the Wentworth Gardner House in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the Hazen Garrison House in Haverhill, Massachusetts, the Cutler-Bartlett House in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and the Ironmaster's House in Saugus, Massachusetts.

|

To furnish these structures and provide props for his photographs, Nutting traveled about the countryside in an early touring car gathering what he referred to as Pilgrim century furniture, as well as several hundred pieces of wrought iron, ceramics, pewter, and treenware (wooden table and kitchen wares). The interiors and their furnishings provided him with an additional return when he opened the houses to tourists for a 25-cent admission fee.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Joshua Parmenter Cupboard, circa 1695. Oak, maple, pine. Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Wallace Nutting Collection; gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr. 1926.291.

|

With great marketing savvy, Nutting expanded his enterprises further in 1917 when he began a reproduction furniture business. He felt that the furniture made by companies in woodworking cities such as Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Gardner, Massachusetts, was "without style, without substantiality...without any possible excuse for being," and argued that no new furniture aesthetic could "bear comparison, side by side for a moment with the old styles."6 Seeking to produce furnishings of "beauty and merit" for the present age, Nutting offered high-end reproductions and marketed them as soundly constructed, historically accurate (read morally superior) pieces for the home (Figs. 3 and 4). In the same year, he established a forge behind the Ironmaster's House in Saugus, Massachusetts, and began producing reproduction ironwork. The minister claimed he lost money in his reproduction businesses, but the endeavors bolstered his reputation as a connoisseur of decorative arts and an authority on early American life.

By 1924, Nutting had divested himself of his colonial picture houses. He shifted his focus to the publishing field, as it required a far smaller capital investment. Nutting introduced the States Beautiful series of travelogues and gradually moved out of the museum trade.

|

|

|

|

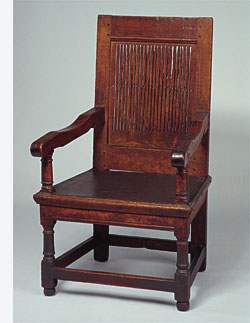

Fig. 6: Joined chair, New Haven colony, circa 1675. Oak. Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Wallace Nutting Collection; gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr. 1926.394.

|

Also, having prototyped the furniture collection for his reproduction business, a concern that would last until 1945, four years after his death, he no longer needed the original objects. In December of 1924, Nutting sold half of his interest in the picture house furnishings to the financer J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr., and agreed to transfer the objects to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut, for exhibition. Arranged in a series of semi-permanent period rooms in the Morgan Memorial Building at the Atheneum, the collection enjoyed widespread publicity and marked the final ascent of Nutting's reputation as a connoisseur and authority on colonial life. Morgan subsequently purchased the remainder of the collection and gave it to the Atheneum as a gift in 1926, thereby fulfilling Nutting's hopes of supplying a museum with the complete furnishings of a large house, "not an article missing, in the period of the Pilgrim century."7

The depth of the Nutting Collection still gives pause. At a time when most collectors found it a challenge to obtain one seventeenth-century court cupboard, Nutting managed to acquire five. He had more than forty chests, sixty chairs, and thirty tables, as well as a variety of cupboards, boxes, cabinets, and desks (Figs. 5-7). While strongest in New England furniture made by English colonists and their descendants, the collection holds significant examples of Dutch inspired forms from New York as well as pieces that originated in the Middle Colonies and rare objects from the South. The collection also includes the hundreds of domestic tools and utensils Nutting gathered to furnish his colonial picture houses. An assemblage of architectural elements and fireplace utensils made of wrought iron combine with such objects as pewter plates, ceramic dishes, and wooden bowls to form a fascinating view of the colonial aesthetic.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Spoon racks, Hudson River Valley, 1750-1775. Pine. Courtesy of Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Wallace Nutting Collection; gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr. 1926.551.553.

|

"Life is not enriched merely by having things unless we also know the things," Nutting wrote.8 True to his words, the minister sought an intimate understanding of colonial objects. Indeed, he claimed to have opened his furniture reproduction business in part "to find out how the old was made."9 Yet Nutting wanted to go beyond materials and construction to understand "the inspiration of the style."10 He invested colonial things with a sense of moral value, representative of an idealized past in which men and women of great character lived honest, productive lives. An innovator in more than one field, Nutting stood out from his competitors in that he developed a closely themed business empire that provided an ideology as well as a product line. Not only did the individual products advertise each other, but the sum proved to be greater than the parts. In this way the country minister from Rockbottom, Massachusetts, foreshadowed contemporary marketing giants such as Martha Stewart and helped make the Colonial Revival an American idiom.

|

The Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, will present the exhibition Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America from June 6 until October 19, 2003. It will then travel to the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania, where it will be on view from February 22 until May 23, 2004.

Trina Evarts Bowman is the Assistant Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Thomas Andrew Denenberg is the Richard Koopman Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Wadsworth Atheneum and author of Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America (2003).

|

|

- For a more thorough study, see Thomas Denenberg,Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2003).

- Wallace Nutting, A Windsor Handbook (Saugus, Mass: Wallace Nutting, Inc., 1917), 171.

- Wallace Nutting, New Hampshire Beautiful (Framingham, Mass: Old America Company, 1923), 181.

- Wallace Nutting, Wallace Nutting's Biography (Framingham, Mass: Old America Company, 1936), 57.

- Joyce Barendson, "Wallace Nutting, An American Tastemaker: The Pictures and Beyond," Winterthur Portfolio 18, no. 2-3 (Summer-Autumn, 1983): 187-212.

- Nutting, Wallace Nutting's Biography, 110, 126.

- Ibid. 106.

- Ibid. 105.

- Ibid. 131.

- Ibid. 105.

|

|

|

|