|

|

|

|

by Pamela A. Ivinski

|

|

|

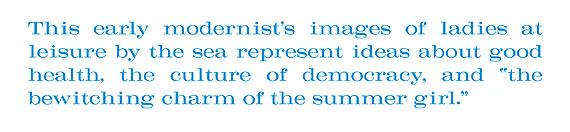

Fig 1: South Boston Pier, ca. 1895–1897. Watercolor,

pencil, and gouache on paper, 19-1/8 x 15-1/4 inches. Adelson Galleries, New York..

|

Art and landscape design writer Mary Caroline Robbins made a bold claim in the January 1897 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. “The parks and park systems are the most important artistic work which has been done in the United States,” she declared, referring above all to the efforts of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, whose works included New York’s Central Park and Boston’s “Emerald Necklace” recreational sites.1 Indeed, while the United States had produced a good number of gifted artists by the turn of the century, the most progressive among them were expatriates, the well-known Mary Cassatt and James McNeill Whistler. Yet at this same moment in history (circa 1895-1897), the artist who would soon be identified as the first modernist working in America--Maurice Prendergast (1858-1924)--was coming into his own, and in doing so created a group of paintings depicting the very sites Robbins celebrated as evidence that “our national aesthetic perception has been touched at last in the right spot and in the wisest way.” Maurice Prendergast: Paintings of America, a current exhibition at Adelson Galleries in New York City with an accompanying catalogue, considers the artist’s portrayal of America, from the early images of New York and Boston-area beaches and parks (Fig. 1) to later idyllic summer seaside scenes (Fig. 2).

|

|

|

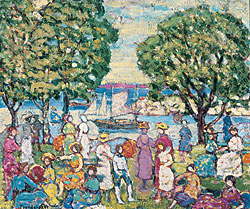

Fig 2: Gloucester Harbor, ca. 1918–1923. Oil on canvas, 23-1/4 x 27-1/2 inches. Private collection, Washington, D.C.

|

Prendergast came of artistic age in an era of new self-consciousness about the American landscape, especially on the East Coast. The country’s oldest states had not only come to seem somewhat small and cramped in comparison to the expansive western territories, but the pressures of immigration and industrialization had led to new concerns about healthful living conditions and the need for centralized planning to regulate development. Practitioners and writers such as Olmsted and Robbins advocated the refurbishment of older parks and the creation of new recreational spaces that would serve to promote physical well-being and the culture of democracy as well as provide lessons in taste.

Prendergast was by no means a social reformer. At times his works seem merely utopian, especially when compared to the muckraking imagery of colleagues such as Robert Henri and John Sloan, with whom he exhibited in the early years of the twentieth century. Yet he was continually attracted to newly opened or recently refurbished recreational spaces in his earliest paintings of the United States and would base his later, often idyllic pictures on the templates he developed during this period. While he would never employ his art to expose deplorable conditions or questionable behavior, as did his friends among the Ashcan School, his art shares in the optimism of turn-of-the-century activists who believed that fresh air and organized leisure activities could remedy social ills. By the time of The Eight’s groundbreaking 1908 exhibition, Prendergast’s work had become more abstract than realistic, leading him to be seen as a peripheral member of this rebellious group of artists. Nonetheless, throughout his life he pursued images that can be characterized as displaying a “democratic outlook…an attitude healthily American,” as one writer described the works of some of his colleagues among The Eight.2

|

|

|

Fig 2: Gloucester Harbor, ca. 1918–1923. Oil on canvas, 23-1/4 x 27-1/2 inches. Private collection, Washington, D.C

|

The sight of summering crowds, drawn from various social classes and nationalities and mingling at seaside resorts and in city parks, also clearly spoke to Prendergast’s own experience, for he had moved to Boston from St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, at the age of 10, and belonged to a family of somewhat limited economic resources. The varied pictures in the present exhibition confirm this artist’s allegiance to the landscape of the country that became his home in 1868, and include depictions of a number of his favored subjects, such as seaside piers and promenades, city parks, New England villages and rocky shores, children at play, and ladies at leisure by the sea.

By the late nineteenth century, the "summer problem" was understood to be an unavoidable facet of modern urban life. “The atmosphere of our large cities in midsummer is so lifeless and oppressive that everyone who can get away for some part of the summer plans to do so, and fathers of families find themselves annually confronted by a serious problem,” writer Robert Grant explained in 1895.3 He also worried about the problem of the “summer girl,” whose main concern was to visit “the gayest watering-places, where she hopes to bathe, play tennis, walk, talk, and drive during the day; paddle, stroll, or sit out during the evening, and dance,”4 while sparing no expense on her wardrobe. To protect the “parental purse,” Grant suggested, “Artistic summer beauty can be readily produced without elaboration, and at a comparatively slight cost, if we only choose to be content with simple effects. The bewitching charm of the summer girl, if analyzed, proves to be based on a few cents a yard and a happy knack of combining colors and trifles.”5

|

|

|

Fig 4: Bathers, ca. 1912. Oil on canvas, 22 x 34 inches. Private collection.

|

From the moment he began to paint American seaside imagery in the mid-1890s Prendergast represented more than a few of these colorfully clad “summer girls.” Yet he always treated the women in his images with the greatest respect, endowing them at times with a monumentality that reveals his admiration for their beauty. This is evident in an early watercolor, Ladies with Parasols (Fig. 3), circa 1896–1897. Two women in bright white dresses and carrying red parasols dominate the image as they sweep along the shore. Their glowing gowns are defined with energetic pencil lines and light gray washes, set off by the figures in black surrounding them. This work is rare among Prendergast’s watercolors because its palette eschews the customary blue tints of seaside imagery.

Though Prendergast reportedly sketched from the live nude model while studying in Paris in the early 1890s and constantly drew women--naked and clothed--in his sketchbooks in the 1900s, it was not until the 1910s that he began to hire his own models and to paint the nude in finished works of art. In images like the gem-toned Bathers (Fig. 4), circa 1912, he filled his compositions with enormous, voluptuous women who recall not only the classical nudes of old master tradition but also the Eastern sources which influenced him at that time. Prendergast combined elements such as poses gleaned from his study of modern dancers, imagery of Hindu goddesses, and scenes of the American seaside into a fantasy world populated by robust naked figures, at times depicted by means of squared patches of color that bring to mind the sparkling tiles of Byzantine mosaics as well as postimpressionist and fauve paint handling.

|

|

|

Fig 5: Figures Under the Flag, ca. 1900–1905. Watercolor and pencil on paper, 201/2 x 101/4 inches. Williams College Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Charles Prendergast. 86.18.70.

|

Even when depicting the most recently opened recreational spaces and the most up-to-date fashions of ladies at leisure, Prendergast created a world that contained elements of the idyllic and the utopian. No scene could possibly be as beautiful as he made it seem. Yet these works would be unimaginable without the democratic impulses that were instrumental in shaping the American landscape; without the reformers, politicians, theorists, entrepreneurs, and philanthropists who sought to provide pleasant outdoor experiences to ameliorate the physical and mental well-being of the country’s denizens and help immigrants to assimilate. Few works better capture the essence of the artist’s imagery of the United States than Figures Under the Flag (Fig. 5). In this circa 1900–1905 watercolor Prendergast treated a favorite motif, ladies at the seaside, painting them at a resort associated with ideas about good health and democratically oriented leisure activities, standing beneath the Stars and Stripes, the very symbol of America.

Excerpted from Pamela A. Ivinski’s essay Maurice Prendergast: Paintings of America in the exhibition catalogue Maurice Prendergast: Paintings of America (New York: Adelson Galleries, 2003).

Maurice Prendergast: Paintings of America, an exhibition and sale of more than fifty important watercolor and oil paintings, will be shown at Adelson Galleries, Inc., in New York City, from May 16 to June 20, 2003.

The exhibition catalogue will include color plates of all the works on view and feature important new scholarship, including essays by Pamela A. Ivinski and Nancy Mowll Mathews, the Eugénie Prendergast Curator at the Williams College Museum of Art and co-author of the Prendergast catalogue raisonne. A reminiscence was written by Warren Adelson, president of the gallery, who maintained a professional association with Eugenie Prendergast, widow of Maurice’s brother Charles (a gifted craftsman and artist in his own right) and heir to the Prendergast estate.

|

On May 15, 2003, there will be a preview of Maurice Prendergast: Paintings of America in celebration of the American Fellows of the Whitney Museum of American Art. On May 19, 2003, there will be an exclusive viewing of the exhibition to benefit the National Breast Cancer Coalition. For further information on these special evenings, please telephone Andrea Maltese at the number below.

|

Adelson Galleries, Inc., is open Monday–Friday, 9:30–5:30, and will be open on Saturdays during this exhibition from 10:00–5:00. The galleries are located in The Mark Hotel, 25 East 77th Street, Third Floor, New York City.

For information and to order the exhibition catalogue, tel. 212.439.6800 or visit www.adelsongalleries.com.

Pamela A. Ivinski contributed to Maurice Brazil Prendergast and Charles Prendergast: A Catalogue Raisonné (Williams College Museum of Art and Prestel, 1990). She currently serves as Senior Research Associate for the Mary Cassatt Catalogue Raisonné Committee, which, along with the John Singer Sargent catalogue raisonné, is supported by Adelson Galleries, Inc.

All illustrations are works by Maurice Prendergast included in the exhibition Maurice Prendergast: Paintings of America at Adelson Galleries, Inc. Photography courtesy of Adelson Galleries, Inc., New York.

|

|

- Mary Caroline Robbins, “Park-Making as a Public Art,” The Atlantic Monthly 79 (January 1897), 86.

- Samuel Swift, “Revolutionary Figures in American Art,” Harper’s Weekly 51 (13 April 1907), quoted in Virginia M. Mecklenburg, “Manufacturing Rebellion: The Ashcan Artists and the Press,” in Metropolitan Lives: The Ashcan Artists and Their New York (Washington, D.C.: National Museum of American Art, in association with W. W. Norton & Co., New York and London, 1995), 205.

- Robert Grant, “The Art of Living. VII. The Summer Problem,” Scribner’s Magazine 18 (July 1895), 50.

- Ibid., 57.

- Ibid., 52.

|

|

|

|