|

|

|

by Jay Robert Stiefel

|

Were it not for the quality of the small amount of pewter that survives with his marks, the role of Philadelphia craftsman Simon Edgell (1687–1742) in the history of American pewter would have been relegated to obscurity. Of the twelve known pieces with Edgell's touchmarks,1 two of the most celebrated are at Winterthur Museum. One of these, a double-domed quart tankard, is engraved with floral decoration and the initials "AM." Ledlie Irwin Laughlin, one of the pioneers of American pewter studies, considered this object "[p]erhaps the earliest of all surviving American [pewter] tankards."2 Equally rare is Winterthur's 19-inch diameter dish, believed by some to be the largest extant pewter charger made by an American pewterer.3

Uncovering information about Edgell, particularly as none of his ledgers or letter books are known to survive, has previously proven to be elusive, with one scholar observing that "little is known of [Edgell] during his twenty-nine years in Philadelphia...."4 Further obscuring Edgell's story is that much written about him is erroneous. Critical portions of his probate inventory have been misquoted or taken out of context. Other sources, such as his many newspaper advertisements and his customers' account books and bills, have been wholly ignored or not previously identified.

|

|

|

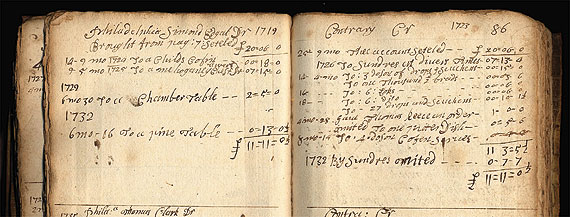

Fig. 3: Account of Simon Edgell, transactions 1719–1729, John Head Account Book, pp. 7–8. George Vaux Papers, American Philosophical Society. Photography by Frank Margeson.

|

In the resulting confusion, divergent views as to Edgell's relative importance emerged. The dean of American decorative arts, Charles Montgomery, hailed Edgell as "Phil- adelphia's most important early pewterer," attributing to his hand the many thousands of pewter wares described in his probate inventory, while disregarding entries suggesting they could have been imports.5 Conversely, pewter scholar J. B. Kerfoot demoted Edgell to just a "reputed" American pewterer - a "pewterer" only in name - lacking the funds necessary to acquire "the valuable outfit of expensive gun-metal moulds needed for the full practice of that craft."6 Both assertions have proven to be incorrect.

Edgell first came to my attention in 1999, recorded amidst other entries in the account book of Philadelphia joiner John Head (1688–1754). Publication of those references in my work on Philadelphia artisanal commerce in January 2001,7 led to a recent article in The Bulletin of the Pewter Collectors Club of America, Inc., devoted solely to Edgell. Highlights are offered here as an inducement to those who may wish to read the fuller story in the PCCA publication.8

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Account of Simon Edgell, transactions repeated, in part, and continued to 1732, John Head Account Book, pp. 7–8. George Vaux Papers, American Philosophical Society, photography by Frank Margeson.

|

Edgell as Pewterer and Brazier

Edgell was born in Cameley, Somerset (now Avon), England. The exact date and place of his birth was a mystery until the recent discovery of his June 10, 1687 baptism at the parish church.9 The earliest record of Edgell's involvement in the pewter trade dates from June 18, 1702, when the books of the Pewterers Company reveal that he was bound in London as an apprentice to William Hux. As Hux habitually blamed others in his employ when defending his substandard pewter before the Court of Assistants, Edgell was probably glad to be rid of him upon gaining his freedom on October 13, 1709, at the age of 22. Edgell's name then disappears from Company records. They divulge no mark registered, no shop opened, nor any further information for him. Whether he stayed in London and worked as a journeyman, returned to Somerset, or immediately emigrated is unknown.

Edgell's date of arrival in Philadelphia remains a matter of conjecture. The first surviving record of his presence is as a witness to a marriage ceremony performed before the Quaker Philadelphia Monthly Meeting on December 13, 1713. The first express indication of his profession is in the May 27, 1717, Minutes of the Common Council where, as a "pewterer," he was admitted a freeman of that city.

By the end of 1717, Edgell had sufficient means to acquire a house and lot in an ideal retail location on High Street near the market stalls. Eleven years later, in June 1728, Edgell rented out the house to the partnership of Benjamin Franklin and Hugh Meredith. What motivated him to give up such a prime retail site requires exploring the nature of Edgell's business and the commercial environment within which he operated.

|

|

The surviving record of Edgell's pewter transactions spans only 1717 to 1730, roughly contemporaneous with his initial occupancy of the High Street property. His earliest documented pewter sales, in 1717, of "Pott[s]" in assorted sizes, dishes, plates, and candlesticks," are found in the household account books of James Logan (1674–1751), secretary to William Penn. Seven years later, in 1724, another transaction records Edgell charging Logan £2/2/9 for a "Limbeck." Logan, a polymath, may have used the alembic, a distillation apparatus, for experiment - or a more convivial purpose.

Further clues to Edgell's business dealings are found in entries for 1719 to 1732 in joiner John Head's account book. The transactions involving Edgell appear either under Edgell's name or, where Head was serving as a merchant intermediary, under the names of Head's other clientele. Entries from 1724 to 1726 pertain to pewter (Figs. 3 and 4). They include "6: plaat," which Edgell delivered to Josier (Josiah) Foster, as well as various other plates, "Basens," porringers, a "Puter Dish," a "Salt Siler" (cellar), and the mending of a "Tankerd" for Head. The Head account book is valuable in that it provides a "real-time" view of Edgell's transactions, showing what forms he actually sold, to whom, when, and at what prices. It also allows for more precise dating of the earliest appearance in Philadelphia of many of these forms. Absent such account book references, Montgomery and others had to rely largely on the probate appraisement of what remained unsold at Edgell's demise - less than current assessment of some forms.

Besides providing insight into Edgell's business practices, Head's entries also reveal particulars of Edgell's personal life. We witness his taste for some of Head's most elaborate furniture in the more costly cedar and mahogany, and his tragedy in the coffins ordered for three of his children over a period of five years.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Beaker, H 4-3/8", TD 3-1/2", BD 3-1/4", with Edgell mark L526 on inside bottom. Collection of Dr. & Mrs. Donald M. Herr.

|

Edgell's pewter transactions also appear in the accounts of two other merchants. In 1729, he sold twelve "plat[e]s" to Richard Hill; and, in 1730, he supplied pewter for John Reynell's ship Delaware. No documented Edgell pewter transactions are known beyond 1730. There exist records of other transactions for him in that period, such as in Benjamin Franklin's accounts, but none involve the sale of pewter. Indeed, Edgell leaves no further documentary trail to pewter until 1741, when imported pewter brought in on his ship, Constantine, is twice advertised.

In addition to pewter, Edgell also had a thriving business in brass. At Edgell's death in 1742, he left a stock of non-pewter base metalware, inventoried at over £600,10 nearly as much as the £794/15/7 accorded his stock of pewter. Additional probate entries, to 200 lbs. of "Old Brass" and to "Brassiers Toolls," together with his 1739 advertisement for a runaway "by Trade a Refiner in Copper, but can Work at the Smith's or Brasier's Business," provide the first incontrovertible proof of an American pewterer's shop also performing braziers' work.11 Thus, rather than Edgell acting solely as a middleman, when in 1726 he sold John Head dozens of escutcheons, pulls, and other hardware for affixing to case furniture and coffins, he very well may have been the producer of some of those brass fittings.

|

Edgell As Merchant, Shipper, and Importer

Edgell's many advertisements in Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette track the transformation of the nature and scope of Edgell's business after he moved from his High Street retail location in 1728. By July 1, 1731, we find him "at Fishbourne's Wharf," a location ideal for the import/export trade and for transactions in bulk. Edgell seems to have expanded his business beyond pewter and brass, for newspaper announcements show that he was by then heavily engaged, together with merchant David Bush, in the shipping of freight (general goods for clients) and passengers to Bristol, the large port near his native village. He was also selling the time of indentured servants brought over from Bristol and nearby Milford, and became involved with servants from the Palatinate.12 Edgell thereafter expanded his shipping business to Jamaica, the Barbadoes, and, eventually, London.

Edgell returned to High (now Market) Street in 1737, perhaps because of its increasing commercial importance resulting from the continuing westward extension of the market stalls down its center. From 1737 to 1741, he and a new partner, Edward Shippen, advertised freight and passage on the ship Constantine. Shippen was formerly James Logan's partner in the lucrative Indian trade, which experience may explain why Edgell's probate inventory was later overflowing with Indian trade goods like "49 Gross & 9 Doz[en] Indian Rings" and "6 Doz & 9 Tomhawks."

Though Edgell was diversifying, he seems to have remained involved with the business of pewter until his death in 1742. But, were the 9,233 items of pewter listed in his probate inventory all made by him, as Montgomery had assumed? I would submit that they were not. Most of them were likely imported. My reasoning is as follows.

|

From at least 1732, Edgell had begun to style himself as a "Merchant." Only one of his frequent ads for goods and services refers to him as a pewterer.13 None ever advertises his sale of pewter. The account book of Philadelphia shipowner Thomas Chalkley records Edgell as importing pewter by the "cask" in 1720 from London merchant Richard King and from an Abraham Ford.14 While we have no further direct evidence of his importation of pewter for the intervening two decades, the Pennsylvania Gazette ran two advertisements in 1741 for the importation of pewter on the Constantine, of which Edgell owned "a Quarter Part." Edgell's probate inventory also lists the considerable debts that he owed to pewter importers at the time of his death. These included Captain Henry Harrison, owed £50, and David Bush, Edgell's erstwhile partner and his largest single creditor, who was owed a whopping £867!15 In fact, two of the three witnesses to Edgell's will were importers of pewter. Franklin, also a creditor, advertised in 1742 that he had "Just imported from London...fine Pewter Stands proper for Offices and Counting-houses."16 Another witness, Myles Strickland, was selling "London Pewter" in Market Street, in August 1744.17

Edgell's importation may have been a necessary reaction to the fact that even his own customers were importing pewter directly from England, such as James Logan did in 1726. While Edgell's precise reasons are uncertain, outside pressures must have been a factor, as Edgell intimate, Benjamin Franklin, was later to reflect:

The working brasiers, cutlers, and pewterers...who have happened to...settle in the colonies, gradually drop the working part of their business, and import their respective goods from England, whence they can have them cheaper and better than they can make. They continue their shops indeed...but become sellers...instead of being makers of these goods.18

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5a: Detail of Edgell mark L526, depicting bird with initials "SE." Collection of Dr. & Mrs. Donald M. Herr.

|

It seems evident that Edgell by his later years probably acted more as a wholesaler or distributor of pewter than as a maker. Montgomery may have had an inkling of this when he queried: "Did...Edgell...supply traders and storekeepers with his wares for resale...?19 This appears to have been the case with the 1741 shipments of pewter on the Constantine, which were advertised as for the shop of merchant John Pole. Another such trader or storekeeper appears to have been joiner/merchant John Head, who debited "Goods by Simond Edgal" to the account of his own customer, Thomas Reese, while simultaneously crediting Edgell for "an order."

Were Edgell principally a seller rather than a maker, it would help explain why so few pieces of Edgell-marked pewter survive (Figs. 5 and 5a), despite the vast quantity of pewter inventoried at his death and the thousands of pieces he presumably sold in his nearly three decades in Philadelphia. The fact that at least two pieces of unmarked pewter exist from the same molds as Edgell-marked pieces also raises the question of whether he stamped his mark on pewter he did not make. No prior writers addressed these incongruities. In my opinion, more than mere attrition played a role.

|

Whatever the extent of his continuing activities as a pewterer, the final word on what Edgell was principally doing'and perhaps how he wished posterity to remember him'was his own. In his will, Edgell styled himself not as a "Pewterer," but as a "Merchant." Nevertheless, Edgell must not have entirely set aside his leather apron. His probate inventory demonstrates that, even at the end, he possessed the necessary raw material and means for making pewter: "Old Pewter" and "Sundry Brass [i.e., bronze] Mold," both essentials of the pewterer's craft.

Jay Robert Stiefel jrstiefel@att.net a decorative arts historian, lecturer, and consultant, is an authority on Philadelphia artisans. His most recent publication is "Simon Edgell (1687–1742)''To a Puter Dish' and Grander Transactions of a London-trained Pewterer in Philadelphia," PCCA Bulletin (Winter 2002). Copies are available to PCCA members. Jay Robert Stiefel jrstiefel@att.net a decorative arts historian, lecturer, and consultant, is an authority on Philadelphia artisans. His most recent publication is "Simon Edgell (1687–1742)''To a Puter Dish' and Grander Transactions of a London-trained Pewterer in Philadelphia," PCCA Bulletin (Winter 2002). Copies are available to PCCA members.

|

|

|

- 1 Several Edgell-marked and attributed pieces are shown in Donald M. Herr, Pewter in Pennsylvania German Churches (Birdsboro, PA: The Pennsylvania German Society, vol. XXIX, 1995), 21, 60, 115–116, 130–131.

- Accession no. 65.553, H. 6-9/16", TD. 4-3/8", BD. 4-3/4". For mark (on inside bottom) and quoted description, see Ledlie Irwin Laughlin, Pewter in America: Its Makers and Their Marks vols. I–II (Barre, Mass.: Barre Publishers 1969), vol. III (1971), in vol. I, plate XVI, fig. 95, and mark L526.

- Accession no. 53.28, D. 19". For marks L528 and 529a (on back) and partial L528a (on front brim), and the mark (on back) of the later eighteenth-century New York pewterer André Michel, who presumably resold it, see Laughlin, vol. III, plate CVII, figs. 528a, 529a.

- Donald L. Fennimore, "Simon Edgell (c.1688–1742)," Philadelphia:Three Centuries of American Art (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1976), 23.

- Charles F. Montgomery, A History of American Pewter (New York: Praeger, 1973), 28, 55, 116, 137.

- J. B. Kerfoot, American Pewter (New York: Crown Publishers, 1942), 30–31.

- Jay Robert Stiefel, "Philadelphia Cabinetmaking and Commerce, 1718–1753: the Account Book of John Head, Joiner;" and Stiefel, "The Head Account Book As Artifact," American Philosophical Society, Library Bulletin, new series, vol. 1, no. 1 (Winter 2001) [http://www.amphilsoc.org/library/bulletin/20011/head.htm]. Prior to my discovery of its significance in May 1999, the Head account book had been uncited and Head's prominence unrecognized.

- "Simon Edgell (1687–1742)''To a Puter Dish' and Grander Transactions of a London-trained Pewterer in Philadelphia," published in The Bulletin of the Pewter Collectors Club of America, Inc., vol. 12, no. 8 (Winter 2002), cover and 352–388. The illustration captions to the present article are drawn from the "Checklist of Extant Simon Edgell Pewter" prepared by Donald M. Herr in the foregoing PCCA Bulletin.

- That discovery by Trish Hayward in the Somerset Record Office, came after I found a reference in the records of the Pewterers Company to Edgell being the son of another Simon, a yeoman of that parish. His mother was Rebekah Maggs. His brother William Edgell, baptized in 1700, was perhaps the Boston pewterer of that name (obit. by 1739), who had a daughter Rebecca and a son Simon.

- His inventory includes over 3-1/2 pages of assorted metalware other than pewter: copper, iron, tin, and brass'often by the dozen or the gross. In 1734, one of Edgell's kettles, of unidentified metal, was taken in credit by Franklin against debits in Edgell's account: "For a Kettle 1/2 between me an[d] Mr Bradford."

- Pennsylvania Gazette (May 10, 1739).

- It is thus not coincidental that he placed several German language ads, nor that nearly half of his surviving attributed work has been found in the collections of Pennsylvania German churches.

- The exception is the 1739 Pennsylvania Gazette ad for his runaway servant.

- Thomas Chalkley account book, 1718–1727, The Library Company of Philadelphia, on deposit in The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, MS #1659, 24, 41. My discovery of these entries was made subsequent to the publication of my PCCA Bulletin article, and thus, appears here for the first time. I would like to thank Beatrice Garvan for her recollection that Chalkley's account books referred to Edgell.

- Laughlin's discussion of the value of Edgell's probate inventory, regrettably, gives a misleadingly prosperous impression of Edgell's finances at his demise. While it is true that "[e]xclusive of real estate Edgell owned at the time of his death possessions valued at almost forty-five hundred pounds [£4,474/1/8 to be precise]," Laughlin fails to mention Edgell's more than one hundred "outstanding Debts," inventoried in the last two pages as totalling £5,710/1/3, an enormous sum and one which far exceeded the value of Edgell's personalty.

- Pennsylvania Gazette, May 20, 1742.

- Ibid., August 16, 1744.

- "The Interest of Great Britain With Regard to The Colonies" (Philadelphia: William Bradford, 1760) pamphlet.

- Montgomery, A History of American Pewter, 3–4.

|

|

|

|