|

|

|

Photography by Erik Kvalsvik

|

|

|

|

The entryway is furnished with a serpentine chest, circa 1773– 1785, attributed to Thomas Jones of Philadelphia; an early nineteenth-century primitive portrait after Gilbert Stuart (1755– 1828); a circa 1800 demi-lune card table from the mid-Atlantic or southern states.

|

As a 5-year-old child growing up in New York, Jay often visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art with his mother. “She wanted to see the Dutch Old Master paintings, I wanted to see the arms and armor,” he says. One day they walked by the American Wing and he was drawn to the three-dimensionality and carving on the furniture. “From then on, every time we visited the museum, we always went to see the furniture.” This interest continued, and while an art history graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1970s, Jay purchased a Philadelphia Queen Anne tilttop table, beginning his decades-long passion for eighteenth-century furniture from this historic city.

By the time Jay met Gabriella, whom he subsequently married, he had amassed quite a collection of furniture and paintings. Born in Europe, Gaby was unfamiliar with American furniture, and rather than share her husband’s enthusiasm for the carved mahogany forms, she migrated toward the clean lines and inlays of Federal period furniture. Their collection now fills most of a five-story town house. The couple has decorated the first few levels with Philadelphia and New York furniture and fine art, the third floor with a collection of Salem, Massachusetts, furniture, and the fourth floor showcases objects from New York, including a French-style bedstead made for merchant Lumin Reed and an armoire with elaborate brass ormolu mounts, both from the shop of Duncan Phyfe (1768–1854).

|

|

|

|

A Federal New York sideboard, circa 1800, features prominently in the dining room. Eight of a set of ten English neoclassical chairs, circa 1800, are placed at the English circa 1810 dining table. The table is set with Limoges plates decorated with Gaby’s family crest, which dates to 9th century Milano; the George II silver épergne by William Cripps is the centerpiece, over which hangs an elegant George II glass chandelier.

|

Jay describes the town house and the objects within as “two years in the building and over thirty years in the making.” When the couple first purchased their home five years ago, they could point a flashlight upward and see all the way to the fifth floor—there were no walls, no floors, no electricity, no water. With what was essentially a clean slate, Jay took the opportunity to design the floor plans for the house. It took seven months of planning, and then a year and a half for contractors to execute. The results are stunning.

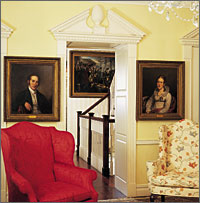

As visitors walk into the entranceway, the impression is one of grandeur and sophistication. The walls are papered with the classically inspired Les Sylphides, which Brunschwig and Fils copied from the 1764 Hatheway House in Suffield, Connecticut; it also hangs in the historic 1786 Philip Syng Physick House in Philadelphia. The imposing serpentine chest attributed to Thomas Jones (active 1773–1785) immediately commands attention. A London-trained joiner, Jones worked in the Philadelphia shop of Jonathan Gostelowe (1744–1795) and is thought to have introduced the serpentine-front, canted-corner chests with which Gostelowe is often associated.1 This is only one of three such chests known with blind fretwork applied to the canted corners, which are usually fluted—a second is in the Hennage collection and the third is illustrated in Hornor’s Blue Book.

|

|

|

|

A Simon Willard tall case clock, circa 1792–1796, stands in the upstairs hallway opposite an Attic black figure column krater, circa 540 b.c. In the living room beyond is a Philadelphia camel-back sofa, circa 1770; a Philadelphia easy chair, circa 1770 (right); a New York easy chair, circa 1765; and a large English 1729 silver salver for which Jay designed the base. The salver bears an elaborate crest of the Bishop of London, for whom it was made.

|

Above the chest is a primitive painting by an unknown artist after Gilbert Stuart’s 1806 portrait of George Washington at Dorchester Heights, now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The painting once hung in Llewellyn, the Virginia home of Warner Washington II, a nephew of the first commander-in-chief. The image depicts a triumphant General Washington after his campaign in March of 1776 against British troops entrenched at Boston harbor. “Researching and understanding the objects we own is part of the process and joy of collecting,” says Jay. “Maybe someday we will discover the identity of this artist, for instance.”

Down the hallway is the dining room, which overlooks a courtyard of trees. “When the service doors are closed,” says Gaby, “you are enveloped by nature. With the images around you, it’s like being back in time.” The wallpaper depicts “Views of North America,” first printed in 1834 by Jean Zuber in Alsace. The panels present famous American scenes including Niagara Falls, West Point, and Boston Harbor. Zuber still manufactures the wood block-printed paper, and Gaby notes that “it took nine months to receive our order once it was placed—the wait was well worth it though.”

The central piece of furniture in the room is the sideboard. Made in New York circa 1800, it features an undulating façade, highly figured veneers, and bookend inlays often associated with furniture from the city; unusual are the tombstone-inlaid drawers. “The sideboard is very graceful, yet big enough so that I can store many things in it,” says Gaby, who has taken advantage of the large size of the New York piece. She then notes that the George II silver épergne on the English classical dining table “was illustrated in Forbes as one of the treasures of the year 2000— unbeknownst to us!”

|

|

|

|

A York, Pennsylvania, armchair, circa 1770, is placed before the Miranus Willett secretary, circa 1770, New York. A New York chest, circa 1765, with faux-hinged drawers that open to reveal a cupboard, is below a John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) study, a Thomas Sully (1783–1872) self-portrait, and Sully’s Masonic apron.

|

Placed at the top of the stairs in the second-floor hallway is an oversized tall case clock with a dial signed by Simon Willard of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Willard was the most prolific clockmaker in New England during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and his clocks are among the most highly sought by collectors. This clock is further distinguished by the presence of the original oversized engraved label glued to the inside of the waist door. Engraved by Joseph N. Russell, the label dates the manufacture of the clock between 1792 and 1796. This clock is one of a pair; the mate is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. “This clock has it all—painted dial, inlaid case, signature, and the label,” Jay notes.

At one end of the hallway is Jay’s study, where a secretary made by Marinus Willett (1740–1830), the cabinetmaker, merchant, soldier, and one-time mayor of New York City, is prominently placed. Willett made the piece for his own home, integrating a W in the center of the fretwork. “Willett lived less than two miles from where I grew up, so this secretary holds special meaning for me. Israel Sack bought it right out of the house directly from the family in 1928,” notes Jay. The breadth of this secretary is typical of eighteenth century furniture made in New York, which in form was closer to English prototypes than the New England counterparts. Surviving objects from this time period in New York history are rare because of the 1766 fire and the loss of objects when Loyalists fled the city with the British in 1783.

|

|

|

|

One of a pair of English sconces with opposing eagles, circa 1760s. Jay redesigned the door and window surrounds of the living room to accommodate this elaborate pair of rococo sconces.

|

To the left of the secretary are two portraits, one by John Singleton Copley (1738–1815) and the other by Thomas Sully (1783–1872). The Copley descended in the Amory family. There is discussion as to whether it is a self-portrait or a study for a family portrait, possibly depicting Copley’s brother-in-law. The Sully is a self-portrait. Referred to as “the Prince of American portrait painters,” Sully is recognized for his intimate, engaging depictions of his sitters, which he has captured here in this image of himself. As Jay notes, “This particular portrait was painted no doubt with special care as Sully inscribed it on the back, To my daughter Blanch, T.S. 1867 Oct.” Sully recorded this painting in his daybook as “‘The Artist,’ painted from a daguerreotype for Blanch, begun Sept. 27 1867, finished Oct. 4 1867.”2 Jay was particularly pleased to purchase this painting because of its personal connection to Sully and his daughter, and its additional documents: Sully’s Masonic apron and presentation medal. Both the apron and medal carry the inscription Presented to Thomas Sully, Esq./By the LIGHT GUARD/of the City of New York/July the 4th 1835.

Two other favorite paintings of Jay’s are the Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) portraits of his daughter Sybilla Miriam Peale and her husband, Andrew Summers. The couple was married in 1815; the portraits were given as a wedding gift by early 1816. Sybilla wears a miniature portrait of her mother, Hannah Moore Peale, which was painted by her uncle, James Peale (1749–1831). While Charles is known as a portrait painter, naturalist, museum visionary, and active member of the Philadelphia artistic community, James was a highly accomplished miniaturist and landscape painter. “I like self portraits. There is a personal connection with the artist that is not present in other paintings. Since I could not purchase a self-portrait of Peale, this pair was the next best thing,” says Jay.

|

|

|

|

Portraits by Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) are in the foreground. Moses Wight’s (1827–1895) Washington’s Farewell to his Officers, New York, 1783 (hallway), circa 1850, hung at Fraunces Tavern in lower Manhattan for many years and furthers Jay’s childhood connection with the city.

|

Down the stair hall from the den is the living room. “The living room was entirely designed by my husband,” says Gaby, “with the doorway pediments and surrounds copied from a mansion in Fairmont Park.” The English mantel was discovered with the help of interior designer Ralph Harvard, who also suggested colors for the woodwork throughout the house.3

A Philadelphia Chippendale high chest is a centerpiece of the couple’s collection. “I love the gutsy, early gnarled feet,” says Jay, “and even though my wife usually prefers Federal furniture, this is her favorite piece—it’s easy to understand why.” Research by Alan Miller and Luke Beckerdite indicates that this high chest was carved by the “pre-Garvan” carver, a craftsman responsible for the details on a number of early Philadelphia rococo pieces made in the 1750s and 1760s that have matching elements with this piece.4 While the couple’s high chest may at first appear to be a mate to their dressing table, the latter piece actually features shells and foliate carving attributed to Nicholas Bernard and Martin Jugiez, in partnership from 1762 until 1785. As any collector would be pleased to point out, two prominent published examples share nearly identical construction and carving features, one of which is illustrated as the frontispiece of Hornor’s Blue Book, and the other is pictured in one of Luke Beckerdite’s articles on Philadelphia carving shops.5 Less noticeable because of its smaller scale is an ornately carved Philadelphia side chair, one of the couple’s most treasured pieces of Philadelphia furniture. “I had no great chairs until Ipurchased this one,” Jay notes. This chair would certainly be categorized as great. The cabochon, ruffle leg carvings, and distinctive asymmetrical rocaille skirt carving are identical to the elements on the Gratz family high chest, dressing table, and a chair from a set made for the marriage of Michael Gratz and Miriam Simon in 1769, now in the Winterthur Museum. The chair descended in a Canadian family with the Cadwalader hairy-paw card tables now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

|

|

|

The living room is furnished predominantly with Philadelphia furniture, most prominent of which is the Philadelphia high chest, circa 1755. Not previously illustrated is a Philadelphia tea table, circa 1760; a Philadelphia dressing table, circa 1765; a Gratz family side chair, Philadelphia, 1769; an English looking glass, circa 1770; and one of a pair of circa 1745 Philadelphia side chairs associated with the shop of William Savory (also below right). Over the mantel hangs a scene of Venice by Thomas Moran (1837–1926), dated 1912. Not shown is an inlaid Pembroke table, circa 1790, and a New York sofa attributed to Slover and Taylor, identical to one at Winterthur made in 1803.

|

Over the elaborately carved mantel, which sets a formal tone to the room and unites the architecture with the carved elements of the furniture, hangs a scene of Venice painted by Thomas Moran (1837–1926). “I am from Northern Italy and love Venice, so I got a bit carried away when I purchased this painting and bid above budget. I called my husband and told him that I had good news and bad. We had bought the painting, but I had spent more than the agreed amount,” concedes Gaby. “It took him a while, but he now admits to liking the painting,” she adds.

|

|

|

|

Portrait of 14-year-old Isabella Lothrop, by William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), circa 1913.

|

On the opposite wall is a large portrait of an eighteenth-century young gentleman courtier painted by William Merritt Chase (1849–1915) in 1912. It is actually a prize that was won by the sitter, 14-year-old Isabella Lothrop, for the best costume at Chase’s Bruges summer painting school. Chase brought the painting home and showed it at numerous museum exhibitions before returning it to its owner. “The portrait is special because it reminds me of my daughter,” says Jay. Next to it is a large Guy Carleton Wiggins (1883–1962) New York snow scene, Broad Street in Winter, New York. “I love American Impressionists,” says Gaby, “and Wiggins draws me in; it’s almost as if I can get lost in his snow storms.”

|

|

|

Broad Street in Winter, New York, by Guy Wiggins (1883–1962).

|

When asked what they have learned over the years, they note, “When assembling a collection, you need the advice of people who know more than you do. Leigh Keno, on furniture, and Debra Force, on paintings, for example, regularly consult with us when we make purchases.” The couple also comments that it is important to focus the collection, not letting it get too scattered, and to understand that different types of objects can be complementary—such as Greek vases and Federal furniture, which both display classical elements. “I’ve made some mistakes and learned the hard way,” notes Jay. “Those pieces are no longer here. You gain from your experiences—it’s a continual learning process.”

|

- See Deborah Federhen, The Magazine Antiques (May 1988): 1174–1183.

- Recorded in Biddle and Fielding as number 1741. The daguerreotype is illustrated as the frontispiece in Munroe Fabian, The Works of Thomas Sully (National Portrait Gallery, 1983). The albumin silver print is dated to ca. 1865, when Sully was 82 years old. This and other information in this paragraph was gained through a conversation with Carrie Rebora Barratt, Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- An article on Harvard is published in this issue on pp. 266–271.

- Closely related examples from the group include the high chest at the de Young Museum in San Francisco and a dressing table from the Nicholson collection sold at Christie’s, January 1995.

- Beckerdite, “Philadelphia Carving Shops, Part II,” The Magazine Antiques (September 1985): 507.

|

|

|