|

|

|

Christian Schussele (French-American, 1824–1879), Game of Marbles, 1854. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Utah Museum of Art, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Christian Schussele emigrated from France in 1848 and settled in Philadelphia, where he taught fine arts in the academic tradition (a young Thomas Eakins was his hand-picked assistant at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts). Schussele, who worked in chromolithography and wood engraving, became one of the first artists in America to employ mechanical color printing. In response to mid-nineteenth-century public taste, Schussele created colorful prints and paintings of lighthearted themes such as dancing, singing, and children at play.

|

In the 1840s, Queen Victoria dressed her young sons in pint-size sailor suits, a notion of hers that set a fashion for boys for a century, lingering even today. “Such a darling,” was how the queen described her three-year-old, Prince Alfred, in his blue-and-white outfit. Specialized children’s clothing—made for the purpose of evoking an adorable look—was something new to Victorian England, and it appeared at a time when infant mortality, though still high, was on the decline.

In contrast, half a century earlier, Massachusetts native Sarah Bryant, mother of poet William Cullen Bryant, indicated in her circa 1790s diary that she never made clothing for her children until they were safely delivered, nor did she call them by name until they were several months old. This not uncommon hesitancy to become too closely attached to children stemmed from a concern—based on sad statistics—that they might not survive. In eighteenth-century New England, childhood was overshadowed by both the fear of premature death and of mortal sin. A God-fearing Puritan upbringing, rooted in Calvinist Europe, included “breaking the will” of children to keep them from sinning.

While not without warmth and affection, a child’s life into the nineteenth century meant harsh discipline, hard work, and few occasions for toys. By the time Queen Victoria’s nine healthy children were born—between 1840 and 1857—the decrease in infant mortality allowed parents to enjoy the sweetness of their child’s early years. Concurrently, the Industrial Revolution created a middle class with more leisure time for family play and the means to buy toys and games.

"Children are a blessing great but dangerous."

-John Robinson, New Essays; Or, Observations Divine and Moral, 1628.

|

|

|

|

François-Hubert Drouais (French, 1727–1775), Portrait of the Children of the Comte de Bethune Playing the Guitar, 1761. Oil on canvas. Eugenia Woodward Hitt Collection. Courtesy of Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama.

As a child, Eugenia Woodward Hitt (1905–1990) began her distinguished collection of French antiques and paintings. The portrait shown here is part of her generous bequest of more than 900 objects and 101 artworks to the Birmingham Museum of Art. The spectacular Hitt collection of eighteenth-century French art was joined this fall by a complementary major traveling exhibition, Matieres de Rêves: Stuff of Dreams from the Paris Musée des Arts Decoratifs, on view through January 5, 2003. Tel. 205.254.2565; www.artsBMA.org.

|

The rise of an ideal of childhood had begun, and nineteenth-century material culture reflected the change. The variety and accessibility of toys increased, and children’s literature developed, softening on the moralizing themes and introducing fantasies where bunnies talk and mad tea parties take place. The Puritan notion that children were naturally disposed to do evil gave way to the idea that babes are born innocent and good; their earliest years to be cherished and made memorable. Into the present day, objects that rekindle childhood memories are beloved, making every generation’s toys and games valued collectibles. So you’ll find it no surprise that grandma’s Victorian Eastlake collapsible high chair now fetches $1,200, or that dad’s Buddy L truck brings $3,000. Not to mention Lincoln Logs, scarcely a few decades old, but considered a desirable “vintage” toy.

The illustrations shown here include objects and works of art relating to childhood in current exhibitions, museum collections, and on the market.

Sock monkeys, a tribute to Yankee thrift and inventiveness, became part of American childhood in 1953, when the Nelson Knitting Co. registered its design for turning a pair of socks into a stuffed toy. As interpreted by generations of home sewers, the sock monkey is now seen as a form of folk art, its basic pattern transformed through costuming, stitching, and stuffing.

About 100 of these whimsical and unique stuffed toys, from a private collection of 1,500, are included in the eclectic exhibition Pictures, Patents, Monkeys, and More…On Collecting at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, through December 15. Tel. 215.898.5911; www.icaphila.org.

Classic toys such as Lincoln Logs, Steiff animals, Lionel trains, and Legos are part of our collective memories. Fun selections from the nineteenth century to the present are on view now through January 5, 2003, in Good Then, Good Always: Toys and Memories at the Concord Museum, Concord, Mass. Tel. 978.369.9763; www.concordmuseum.org.

The eldest of five children born to a wealthy Parisian family, Edgar Degas spent his childhood in a strict boarding school where he received very poor marks in drawing class. This sympathetic but unsentimental portrait, based on a Renaissance portrait type, depicts the artist’s youngest brother.

|

|

|

|

|

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917), René de Gas (1845–1926), ca. 1855. Oil on canvas. Purchased, Drayton Hillyer Fund. Courtesy of Smith College Museum of Art, Northhampton, Mass.

|

|

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), The Wyndham Sisters, 1900. Oil on canvas. Wolfe Fund, Catherine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York. Photo courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

|

|

|

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925), The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882. Oil on canvas. Gift of Mary Louise Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

The casual Boit sisters, captured pausing from a moment’s play, meet the sophisticated Wyndham sisters, young, married, and confidently poised. John Singer Sargent’s portraits of the seven collective sisters are united in a special installation at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston through January 5, 2003. Tel. 617.267.9300; www.mfa.org.

Great Expectations: John Singer Sargent Painting Children, a major exhibition organized by American art curator Barbara Gallati, is scheduled to open in October 2004 at the Brooklyn Museum of Art. The exhibition will be accompanied by a comprehensive book on the subject by Gallati with contributions by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston curator Erica Hirshler and Sargent expert Richard Ormond. Tel. 718.638.5000; www.brooklynart.org.

"This is the age of the child. To have the child painted or photographed has become a habit with all the elders."

-Art critic Sadakichi Hartmann, Cosmopoltan, 1907.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Doll’s bed, ca. 1840. H. 241/2" W. 173/4" L. 301/4". Courtesy of Swan Tavern Antiques, Yorktown, Virginia.

|

|

Philadelphia sampler by Eliza Ann Fow, age 11, ca. 1825. Verse is titled “Self-Government.” Courtesy of M. Finkel & Daughter, Philadelphia, Penn.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Joseph H. Davis (American, 19th century), Family Portrait, ca. 1820. Pencil and ink on paper. Courtesy of David Wheatcroft, LLC., Westborough, Mass.

|

|

Marie Danforth Page (American, 1869–1940), Portrait of a Boy in a Red Shirt, 1934. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Lepore Fine Arts, Newburyport, Mass.

|

|

|

|

|

|

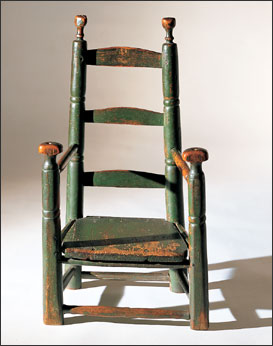

Child’s maple and ash three-slat sausage-turned armchair. Early- eighteenth-century green paint surface. Probably Connecticut, ca. 1720–1740. Courtesy of Nathan Liverant and Son, LLC., Colchester, Conn.

|

|

John George Brown (Scottish-American, 1831–1913), The Dilettante, 1882. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Debra Force Fine Art, Inc., New York.

|

J. G. Brown’s academic style of portraiture appealed to the sensibilities of the well-to-do nineteenth-century middle class. Especially popular were his portraits and genre scenes featuring children playing games in rural New England settings and New York City scenes of street urchins and bootblacks (shoeshine boys). So profitable were his portrayals of these hapless city youths that the word copyright often accompanies Brown’s signature on the finished canvas.

According to Brown expert Dr. Martha Hoppin, the artist painted at least three other variations of The Dilettante in 1882. In each work, he depicted a different working-class boy, posing him sitting or standing and alternately admiring a broken ceramic piece, a figurine, and a teapot. The Dilettante humorously presents the tale of a young proletarian who, while lacking upper-class connoisseurship, is not without the capacity to identify and appreciate a treasure when found.

Suggested Reading:

|

|

|

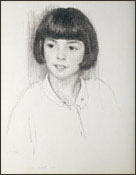

Lilian Westcott Hale (American, 1880– 1963), Portrait of Harriet Blake, 1925, also titled Harriet Blake #2. Charcoal on paper. Private collection; photo courtesy

of Brock & Co., Carlisle, Mass. |

Brant, Sandra and Elissa Cullman. Small Folk; A Celebration of Childhood in America. New York: E.P. Dutton and the Museum of American Folk Art, 1980.

Calvert, Karin. Children in the House; The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600–1900. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1992.

Earle, Alice Morse. Child Life in Colonial Days. First published in 1899. Reprinted by Berkshire House, 1993.

Fischer, David Hackett. Albion’s Seed, Four British Folkways in America. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Her Royal Highness, The Duchess of York, with Benita Stoney. Victoria and Albert, A Family Life at Osborne House. New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1991.

Nylander, Jane C. Our Own Snug Fireside, Images of the New England Home, 1760–1860. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1993.

Steward, James Christen. The New Child; British Art and the Origins of Modern Childhood, 1730–1830. Berkeley, California: University Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley.

|