My love affair with dealing and collecting. By Peter Tillou.

|

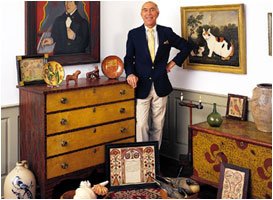

The Philadelphia Antiques Show, Winter Antiques Show, Maastricht and Grosvenor House have two things in common: Firstly, they are some of the world’s finest shows, inviting only top dealers to exhibit. Secondly is Peter Tillou. Peter has exhibited at all of these shows, and has been on the board of directors and vetting committee for Maastricht. His expert knowledge spans a broad range of specialties from European and American paintings and furniture, to arms and armor, to African and pre-Columbian art. He has helped develop some of the finest collections in the world for both museums and collectors, and is responsible for developing one of the world’s greatest collections of 17th century still life paintings. Peter, who buys predominantly from dealers, families and private collections, has galleries in Connecticut, New York City and London. His reputation for honesty and integrity is impeccable and he commands the utmost respect from museum curators, colleagues and clients. As Johnny Van Haeften, a leading fine art dealer in London remarked, “Through Peter’s openness, honesty, enthusiasm and knowledge, Peter keeps his a customers for life.”

With the Winter Antiques Show recently concluding, and Philadelphia and Maastricht soon upon us, I thought it appropriate and exciting to learn how Peter developed into such an accomplished collector and dealer of so many different specialties, turning his lifelong passion into a career.

| |

| Peter Tillou in his gallery. |

Collecting was an early passion for me, which has lasted and brought me joy through my entire life.

I began buying old coins at the age of eight, and as this interest in rare and beautiful objects developed, I discovered every hidden alley and old shop in Buffalo, New York, the town where I grew up, including the Salvation Army and Goodwill stores, which in those days were absolute gold mines. At age twelve, my sense for trading and dealing had already begun to develop, and I made my first real deal. Having seen an old sword in Sal Licata’s pawn shop downtown, I found that I needed something valuable to trade for it. I went into the attic of our family house, came across an old violin that seemed to fit my needs, and marched downtown with that violin under my arm to trade it for the sword.

My dear mother, who was a well-known portrait artist at that time, also loved art and antiques, and would take me to the Albright-Knox Museum in Buffalo, and also in the car on buying jaunts to help further my understanding of old things. On one of these occasions as we rode along, she asked whether I had seen her old violin.

With a little anxiety, I asked if it was something special. It was then that she informed me that it was the instrument she had used as a concert violinist in her youth. When I reluctantly informed her that I had traded it for a sword, she demanded that I go right down to Sal’s and trade it back, but of course it was gone. Sal had sold it to a violin dealer months before. I had learned an important lesson, and from then on was more respectful (though no less covetous!) of all the other things in our house that I yearned to sell.

My uncle, a paleontologist who sold antiques as a hobby, often participated in antique shows. I began to join him at these shows at age fourteen, bringing along a carpet-bag full of antique objects and old guns which I would sell in his stand. In the following years, before I entered college at Ohio Wesleyan University, I traveled to cities all over the Northeast, including New York, and met the great antiquarians of the period, gleaning every bit of knowledge I could from them. One learning experience creates the foundation for other learning experiences, and my knowledge grew in leaps and bounds in those days as I was buying and selling from the trunk of my car, traveling to Europe on a regular basis and selling at antique shows throughout my college years.

Among those who influenced me most in my early dealing days in the 1950s were Robert Abels and Joe Kindig in the area of fine antique guns, and my dear friend John Veenschoten, who often loaned me hard cash to help finance my buying trips to Europe. In the 1950s and 60s, Martha Jackson trained my eye for contemporary painting, and from the early 1950s, Garth Oberlander taught me about the world of art auctions. On a trip to England during college I met Paul Rich, a seasoned dealer by that time, who became a dear friend and who took me with him on trips throughout Great Britain to help me learn about all periods of painting. Perhaps most important of all, however, were my mother and father, who always encouraged my love for beautiful things, my passion for collecting, as well as understanding what one could have perceived as an eccentric lifestyle at my young age.

As much as I learned from my mentors, however, more often than not I forged ahead on my own, challenging my eye in areas unknown to those who had previously taught me. On a drive between Cleveland and Buffalo in 1954, I came across an antique shop and, naturally, stopped in to see what I could find. It was here that I found my first American folk painting, a great still life that hangs in my kitchen in Litchfield to this day. It cost me $50. Having developed a sound knowledge in coins, arms and armor, and early American blown glass, I poured my energies into learning about American folk painting, which became one of several central focal points in my life as a collector and dealer. I had always been attracted to the keen sense of design and abstraction of these self-trained artists. The strong individualism and honest expression of these creative men and women drew me to their work, and I consciously sought out paintings that I felt expressed the height of achievement in this field.

| |

| Fig. 1 Portrait of Andrew Jackson Ten Broeck by Ammi Phillips. |

An example of the kind of painting that thrilled me most is the portrait of Andrew Jackson Ten Broeck by Ammi Phillips (fig. 1), which I first discovered in 1974 in the collection of the Ten Broeck family in upper New York State, who had called me with regard to two paintings of Ten Broeck children painted by Phillips that they owned. The paintings sounded absolutely breathtaking, so I dashed off the next day to meet the family and to see these two Phillips masterpieces. I was heartsick when the family sent me away empty-handed, even though they had promised to sell me the pictures after discussing it among themselves. A few weeks later, my dear friend and kindred spirit in the folk art field, Mary Allis, called me and said, “Honey, you’ve been up seeing the Ten Broeck paintings. It is very important for me to buy both those pictures to have the prestige, but after I’ve bought them, I’ll let you have one and I’ll keep one. What do you think about this arrangement, rather than competing against one another?” Since she was the matriarch of the field, I knew it was best to agree to this compromise, but I specified that I wanted the portrait of Andrew Jackson for my own collection.

After she purchased the paintings, Mary called me, very excited, and ordered me to the opening of the Southport Antiques Show, letting me know I had better be prepared for some excitement since she had the Ten Broeck boy for me. When I walked in and saw the painting, my heart was thumping with joy, and Mary said, “Kiddo, you had better sit down when you hear the price you’re going to have to pay me!” Needless to say, my enthusiasm was somewhat dampened, since it was obvious that Mary understood what an absolute masterpiece this particular Phillips was, and I was going to have to pay dearly. She mentioned a price that was triple the world record for Phillips - and far beyond what I would have had to pay the family — and said, “That’s the price, honey, and you have to have it.” She was right, so I bit my lip and paid her. Given my emotional reaction to this treasure, I felt at that moment that I would have paid any price. From that moment on Mary took great glee in telling people how she had brought Peter Tillou to his knees, but that painting, which is still in my collection, has brought me so much pleasure over more than twenty-five years that it was well worth it! The essence of the lesson here is that one should attempt to acquire the best in any field that one’s financial ability will allow.

It was perhaps in the development of my folk art collection that I began to understand what I feel should be at the core of every collection: a response to pure beauty. Since I was a young collector and dealer, I have tried to judge all works of art by certain intuitive criteria: Do I have an immediate emotional reaction to a work of art? Is it beautiful or dramatic? Does it have good color and surface, fine proportions, a successful composition, a level of quality, originality and historical importance? I developed strong feelings at an early age - which I still hold - that in an ideal environment, no works of art would be signed, and each work would be judged solely on its own quality and merit. So often, creations by big names are sold for huge prices, even though they are poor examples as works of art.

To this day, I encourage young collectors to give themselves the experiences I took advantage of as a young man. Knowledge breeds excitement. Go to museums and carefully study what you see; develop relationships with private collectors, curators and dealers, and gain an understanding of the principles that have guided their choices. In areas in which you do not have a natural eye, search out people of knowledge and good judgment for advice. I have always been thirsty to go in search of what might be better than what I have bought in every field.

In the over fifty years of my love affair with dealing and collecting, with a near constant schedule of sixteen- and eighteen-hour days, I have found pleasure in an eclectic range of fields: rare coins, European and American arms and armor, American Indian art, American blown glass, vintage classic cars from the 1930s, American furniture and Folk art, Old Master and nineteenth-century paintings, European furniture, European and American medals, silver, pottery and porcelain, antiquities, and African and pre-Columbian art. I still take as much joy in finding a tiny treasure by an unknown hand as I do in acquiring a great painting by a world-renowned artist in the old master field. And I am still learning every day through my relationships with other collectors and dealers and, even more importantly, with that most valuable of assets - my own two eyes. The hunt goes on!

This article was originally published in Antiques & Fine Art magazine, fully digitized versions are available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|