he year is 1875. Joseph Lewney, a sailor with the screw schooner Lizzie, lounges on deck, his back against the base of the main mast. The sun beats down, forcing him to wipe the sweat from his brow so it doesn’t drip on his work. He glances up at the sail, slack from lack of wind, sighs, and then plunges his needle threaded with green wool back into the ocean he is creating on a piece of scrap sailcloth. he year is 1875. Joseph Lewney, a sailor with the screw schooner Lizzie, lounges on deck, his back against the base of the main mast. The sun beats down, forcing him to wipe the sweat from his brow so it doesn’t drip on his work. He glances up at the sail, slack from lack of wind, sighs, and then plunges his needle threaded with green wool back into the ocean he is creating on a piece of scrap sailcloth.

|

|

|

Figure 1: An unusual wool work of the Lissie with individual sailors seen on deck, signed JL (lower left), circa 1875. Joseph Lewney, age 46, was a registered crew member on the Lissie in 1875 and may be the sailor who created this Woolie. The screw schooner Lissie was a merchant ship with three masts and two steam funnels. She was built in 1857 in Liverpool and had an iron hull. She was 178.5 feet in length, 25.3 feet in breadth, 8.8 feet in depth in hold and 323 gross tons.

|

Although this scene is imaginary, the crew agreement dated 1875 for the Lizzie, also called Lissie, lists Joseph Lewney, age 46, from the Isle of Man as one of its sailors. The Lizzie, Figure 1, a wool work in the collection of Earle D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge contains the initials J.L. in the lower left corner. It is quite likely that Lewney was the sailor who created this piece of art. This picture is only one of thousands of British wool works that have become highly collectible in both British and American markets.

From about 1840 to World War I, many British sailors passed the long hours in port or on the open sea by sewing these wool pictures, commonly called Woolies. Many have a naive charm, but some are so well executed that they rival their counterparts in oil. Primarily Woolies depict ships, but some are known to contain other subjects such as patriotic symbols. Most often, they were portraits of the sailor’s vessel, made as a memory of his voyage or as a gift to a loved one. As Woolies were works of pride or sentiment, none were done in bad taste or caricature. Unfortunately, the names of the artists have been lost to history because Woolies tend to be unsigned. But sometimes they give us small clues as to their origin. Woolies often are dated, initialed or have the name of the ship sewn into the picture. Still, identifying a ship can be complicated. Names often were passed from ship to ship. Vessels underwent technological advances that changed their appearances. And often vessels were re-named when they changed ownership.

|

|

|

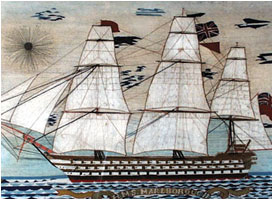

| Figure 2: A fine wool work of the H.M.S. Marlborough in full sail near a lighthouse, circa 1860. This H.M.S. Marlborough (1855-1904) is the fourth ship bearing this name. Carrying 131 guns, she was one of the largest wooden ships ever built. At the time, she was the largest vessel in the British navy and was launched on August 7, 1855, by Queen Victoria at Portsmouth. |

There is little contemporary literature referring to Woolies. Therefore, much of what is known is based on hypothetical supposition. Most of the vessels depicted fly British flags. Based on this evidence, historians believe that British sailors executed nearly all known wool works. Frequently, ships will fly both the British flag and that of the nation in which the ship is visiting, but some Woolies show only a foreign flag. In this case, one is unable to ascertain whether this is the indication of a foreign hand or simply a view reproduced by a British one.

Steven Banks hypothesizes that their inspiration came from the Chinese embroideries sold to sailors in Hong Kong and the Treaty Ports, which opened to the West in 1842. The height of the craze for wool pictures in the third quarter of the 19th century corroborates this theory.

The enchantment of Woolies is that they are folk art. They were made by the hands of men who were not formally trained in embroidery. Regardless, it is understandable how such tough men could create such delicate pictures. Woolies are the creative product of sailors’ spare time, excess materials and a basic, yet necessary, familiarity with needle and thread. Until the mid-1880s the average seaman had no standard uniform. Not only did he sew his own clothes, but also one of his duties was to maintain the ship’s sails. Furthermore, sailors used embroidery to individualize and embellish their garments, frequently in eccentric designs. Therefore, spare time between watches combined with basic sewing skills and imagination became the rich soil from which the art of Woolies grew.

Most of the materials used to make Woolies were found on board ship. Sail canvas, duck cloth from sailors’ trousers or a simple linen or cotton fabric was used as a base. The stretcher commonly was made from excess wood with simple tenon joints, without wedges. Only the Berlin wool, cotton or silk would need to be brought from home or acquired in a foreign port. Sailors mainly chose to use vivacious colors—chiefly white, blue, red, brown and varying shades of green. Early Woolies are made of naturally dyed wool. After the development of chemical dyes in the mid-1850s, sailors could obtain a greater range of colors at a less expensive price.

Only when the sailor returned home did he frame it. Today collectors frequently place woolies in maple frames, but originally the frames were quite diverse. Sometimes they were made of a simple wood; other times they were highly carved or gilded.

When creating a Woolie, the sailor sometimes first sketched in ink the outlines of the ship and rigging. Using only these schematic designs, he then sewed these pictures in freehand directly onto the canvas using both rudimentary and sophisticated stitches. Indeed, many Woolies show charming liberties taken with the appearance of elements other than the ship.

Sailors employed a great variety of stitches, such as the cross stitch, chain stitch, darning and the quilting technique called trapunto. Judy Jeroy states that the earliest existing examples of Woolies date from the 1830s. These early pieces demonstrate the use of a chain stitch—each stitch seems to go into the stitch before and is less than a quarter of an inch long. An adaptation of this stitch is the long stitch. Used in woolies after 1840, it is a long stitch that leaves little thread on the back, saves wool and makes for much faster sewing. Sailors mainly used wool thread, hence the name Woolie. Nevertheless, cotton and silk play their part. Some unusual Woolies are constructed entirely from cotton or silk. Some sailors even added bits of bone, metal, wood, glass, sequins, mica, carved tortoise shell, whalebone, ebony, beads and sepia-cart-de-vista to bring the embroidery to life. Bridget Crowley states that the texture of the yarn in one or two pictures suggests that sometimes sailors unpicked and re-used the wool of discarded garments.

Attention to the ship’s detail is unusually keen and meticulously accurate in terms of rigging, number of gun ports, signal flags and other identifying features. To create the rigging, sailors mainly used long stitches with fine cotton or linen threads. In some unusual Woolies silk thread or thinly twisted gold threads were used.

|

|

|

| Figure 3: A woolwork picture of ships, including the troopship H.M.S. Himalaya and the torpedo boats Nos. 14 & 17, steaming out of a river mouth into a wide bay with snow-capped hills in the distance, Circa 1885. At 3,438 tons, the H.M.S. Himalaya was almost twice the size of any other ship in the P & O and the largest steamer in the world. She was the result of the development of screw propulsion and could maintain 14 knots with engines alone, and with full sails spread in addition, she could achieve 16 knots. She could seat 170 passengers. During the Crimean War the Admiralty used her for troop transport. |

Although most historians agree that sailors made Woolies, it is likely that many were made on land.

The production of ship portraits in various media was a thriving business in major ports up through World War I. It is quite possible that a number of these portraits were stitched for seamen by artisans familiar with the sea. These other examples made by non-mariners tend not to demonstrate a sailor’s intimate knowledge of a ship’s working parts. Earle D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge had at one time a simple Woolie made by a British Marine. The wool work, of a ship within a roundel surrounded by flags, had on the reverse a note:

Tapestry made by Gunner Charles Wood of 12 Company. R.M. Artillery during his service in Royal Marine Artillery 25 Jan 1870 to 30 January 1882. It was given to his grand-daughter Edith Agnes Wood.

It is this type of personal detail that brings a wool work out of the haziness of history and makes the artist into a real person.

Woolies are considered the least understood of all the mariner’s arts. But from their origin and to their apogee, they documented an important transitional period in shipbuilding. These detailed portraits capture the transformation of vessels from wind to steam propulsion. They also extol the pride and grandeur of the British Navy during the height of imperialism in the mid-19th century.

Some Woolies represent a general type of ship rather than a particular vessel, but most examples are a portrait of an actual ship. Usually Woolies depict just a single ship such as a naval warship, merchant vessel or private yacht. Some do feature multiple vessels or the same vessel shown from various angles. They generally are shown broadside, boasting their distinctive features with full sails and oversize flags unfurled for legibility. Nineteenth-century marine paintings use this same methodology.

|

|

|

| Figure 4: A small wool work depicting a Royal Navy Ship coming toward land with grass-topped cliffs. It is viewed through a demi-lune window and is flanked by the Union Jack and Red Ensign, circa 1875. |

Figure 1, the Lissie, and Figure 2, the H.M.S. Marlborough, exhibit the portraiture style. Woolies have varying degrees of workmanship. The artists of both pictures demonstrate a superb artistic ability. In the Lissie, Lewney shows off his embroidery skills by using varying shades of green thread to create a depth of field seen in the turbulent seas. In addition, he outlines the waves with a coarse white stitch to elaborate this feeling of roughness. The artist of the Marlborough, also created an incredible portrait. The ship shows incredible detailing, down to the number of gun ports. Moreover, the Woolie demonstrates the artist’s creativity and imagination. He goes beyond a simple long stitch to create repeating stylized waves that he contrasts against a non-static stylized sky with a starburst sun. In addition, by subtly changing colors, he makes the ocean realistically disappear into the horizon.

The sailors really showed their skills when they took their wool works beyond the stage of simple ships’ portraiture. They created detailed landscape scenes of faraway ports, naval battles, shipping scenes, rough seas, ships in distress, night scenes, forts, lighthouses and much more. The woolwork depicting the H.M.S. Himalaya, Figure 3, is a fine example of a ship in a landscape scene. It shows multiple boats and other objects of interest in an advanced composition with varying grounds.

Later in the century, patriotism was added to the sailors’ nostalgia for his ship. Woolies sometimes depict a ship fully dressed with signal and national flags hung from the rigging. Ships were placed in a roundel formed like a life preserver or porthole device surrounded by flags of all nations, royal emblems, heraldic symbols, coats of arms, photographs, flowers an allegorical figures. Of course, flags of the Royal Navy and Crimean Allies were used foremost. In some Woolies, elaborately stitched stage curtains frame the ships. Figure 4, a Woolie of a Royal Navy ship heading toward land, depicts the ship in a demi-lune window that is flanked by two British flags: the Union Jack and Red Ensign. Figure 5 shows its ship through a telescopic view that is surrounded by multiple national flags. What makes it particularly enchanting is that two sailors dance a jig below the scene.

These flags and pennants were the language of the sea and now provide important information about the vessels. They can show: nationality or ownership in the case of a merchant ship, yacht club affiliation, place of origin, function and type of the ship, and its destination. A ship dressed with flags and pennants generally announces a special occasion such as the visit of a dignitary. A long streamer indicates that a ship was on her way home.

Woolies reached their height from about 1860-80. Several events led to the eventual demise of the craft. After the advent of steam engine power, the dependency on sails and the large crews required to maintain them came to an end. This in turn influenced the size of the crews as well as their required skills. Sailors no longer needed to know how to sew in order to repair the sails, nor did they need to make their own clothing anymore. Photography also allowed a sailor to remember his travels through photographs instead of his own wool work.

The number of wool works in a collection varies, as do prices. Generally, they sell in the range of $3,000 to $5,000. Some exceptional Woolies do demand higher prices. Recently in August 2000, a large woolwork depicting a naval review sold for a hammer price of $40,000 at auction.

|

|

|

Figure 5: A fine brightly colored wool work depicting a ship viewed through a telescopic window and

surrounded by national flags. Two sailors dance a jig below, circa 1865-75.

|

As with any form of art, once it becomes valuable people make modern imitations with the intent to deceive. Fraudulent needlework often is made with old or distressed frames, nails, linens and paper but with modern wool. Genuine wool works are faded in the front and near their original color in the back where light and other elements have not reached. They also exhibit irregular fading (because wool fades differently), broken threads and, usually, some insect damage. Modern wool works do not have this color differential. Usually the wool has been treated or subdued colors chosen in an attempt to imitate age. Often the technical aspect of the ships is incorrect. The picture in general is neat and does not have a folk quality.

Woolies are a fascinating way to glimpse what a 19th-century sailor saw in his life at sea, as well as to capture a bit of maritime history. Whether done in the coarsest wool or finest silk, each Woolie has its own enchantments and it own story to tell.

For more information regarding British wool works, contact Paul Vandekar of Earle D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge, Inc. Paul Vandekar is one of America’s leading dealers of British wool works and provided

the illustrations. Earle D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge, Inc. also specializes in fine 18th & 19th Century European Ceramics, Furniture and Works of Art, including Textile Pictures, Miniatures and Objet d’ Art. Katherine Manley works in research and development for Earle D. Vandekar of Knightsbridge, Inc. The gallery is located at 305 East 61st Street, New York, NY 10021 and can be reached at 212-308-2022 or at vandekar@bigfoot.com.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Stitches in Time Portray Ships of the Line, Antiques Weekly, August 27, 1993.

Banks, Steven. The Handicrafts of the Sailor. London: David & Charles, Ltd., 1974.

Berezoski, Donald. Offshore Racer Unravels Anatomy of a Woolie. Connoisseur’s Quarterly, Spring 2000, 60-63.

Cooper-Hewitt Museum: Embroidered Ship Portraits Exhibition, June 3 - September 7, 1986.

Crowley, Bridget. Unlikely Art of Jolly Jack Tar. Country Life, November 12, 1992, 46-47.

Jeroy, Judy. Woolies: Embroidered Ship Portraits. Needle Arts, September 1994, 35.

|