|

ven in the digital age, paper is ubiquitous. Subject to great variety and many uses, paper may be utilitarian and ephemeral or a thing of lasting beauty. The choice of a paper is usually dictated by use. Newspapers printed with offset lithography are made of ground wood pulp, which is economical and receptive to the printed word. Artists have a wide choice of papers for their finished work. A sheet with a slight “tooth,” or texture, may be chosen for a drawing in charcoal, while watercolorists often prefer sturdy paper, heavily sized to control the movement of water and allow reworking. Papers used by artists or publishers of fine editions must satisfy aesthetically because they have a direct bearing on the appearance of the drawn or printed image. The choice of paper is as much an intrinsic part of the object as the image itself. ven in the digital age, paper is ubiquitous. Subject to great variety and many uses, paper may be utilitarian and ephemeral or a thing of lasting beauty. The choice of a paper is usually dictated by use. Newspapers printed with offset lithography are made of ground wood pulp, which is economical and receptive to the printed word. Artists have a wide choice of papers for their finished work. A sheet with a slight “tooth,” or texture, may be chosen for a drawing in charcoal, while watercolorists often prefer sturdy paper, heavily sized to control the movement of water and allow reworking. Papers used by artists or publishers of fine editions must satisfy aesthetically because they have a direct bearing on the appearance of the drawn or printed image. The choice of paper is as much an intrinsic part of the object as the image itself.

Many words are used to describe paper. In addition to those that pertain to color, weight, and texture, there is a terminology that defines the manufacture of the sheet: handmade, mold-made, machine-made, wove, and laid. These attributes can be determined by simple visual examination and some familiarity with the history of papermaking.

Handmade Paper: Laid and Wove

Before the invention of the papermaking machine in the late 1700s, all paper was made by hand. A papermaker’s mold, somewhat like a tray with a screen bottom, was dipped into a vat containing a slurry of well-beaten cellulose fibers suspended in water. The mold was removed from the vat, and the sheet was formed on the mold as the water drained away. The damp paper was then couched (removed from the mold) and pressed between wool blankets. In the West the first papers were made from macerated linen or cotton rags, thus the name “rag paper.”

Paper was invented in China approximately 2,000 years ago but did not reach Europe until the twelfth century. The earliest Western rag papers were laid papers. Wove papers evolved during the second half of the eighteenth century. The terms laid and wove refer to the texture of the paper, determined by the structure of the mold screen that leaves its imprint on the sheet.

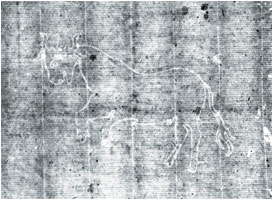

Laid papers are formed on a mesh of small parallel wires held together with heavier chain wires, which cross the smaller ones at right angles. These so-called chain and laid lines can be seen in transmitted light. Paper historians often characterize a paper by measuring the distance between chain lines and the number of laid lines per inch or centimeter. Watermarks, which exist in the earliest Western papers, were created by additional wires applied to the screen in the shape of a figure [Fig. 1].

The subject of numerous publications, watermarks may be useful in dating a paper or determining its provenance.

Wove papers were made on a brass wire mesh similar to a window screen. Wove papers tend to be very smooth with an even distribution of pulp. They were common in Europe by 1790 and in the nineteenth century became the paper of choice for watercolorists.

Machine-made Papers

The papermaking machine, invented in France in the late 1700s, came into widespread use in the next quarter century. Machine-made paper is formed on a continuous web instead of sheet by sheet. Most machine-made papers are wove, although some are specially manufactured to look like laid paper (the so-called machine-laid papers). Today almost all papers are machine-made, although a few small mills and independent artisans still produce handmade papers for special use.

The papermaking machine produced far greater quantities of paper and enabled manufacturers to meet the increasing demands of a growing, more literate middle class. This demand also forced manufacturers to abandon cotton and linen rags in favor of wood, which was cheaper and far more plentiful. As a result, the quality of paper declined. Although wood-derived papers vary greatly depending on the method of manufacture, they are not as permanent and durable as early handmade papers. Because of recent media attention on the vast number of brittle books in the nation’s libraries made of wood pulp papers, and the resulting demand for a more permanent paper, many manufacturers now provide a line of longer-lasting papers. These include products made from high-quality (lignin-free) wood stock and also from cotton or cotton linters. These cotton papers, like their earlier handmade counterparts, are called “rag papers.” At the beginning of the twenty-first century we have come full circle to value paper in its original form.

|

|

|

Fig. 1: Laid paper in transmitted light depicting vertical chain lines and horizontal laid lines with bull watermark, 1881. Courtesy, New England Document Conservation Center.

|

Additional Reading

Hunter, Dard. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1978.

Institute of Paper Science and Technology. Robert C. Williams American Museum of Papermaking. http://www.ipst.edu/amp. Try the “Virtual Tour” and explore “Other Papermaking Sites.”

Turner, Silvie. Which Paper?: A Guide to Choosing and Using Fine Papers for Artists, Craftspeople and Designers. New York: Design Press, 1991.

Karen Brown is the field service representative and Mary Todd Glaser is the director of paper conservation for the Northeast Document Conservation Center, in Andover, Massachusetts, a nonprofit, regional conservation center specializing in the preservation of paper-based materials

for libraries, archives, museums, and other records-holding institutions, as well as private collectors. Visit the Center on the web at www.nedcc.org.

Collectors’ Corner is a regular feature that presents useful information for collectors learning about antiques and fine art.

|