|

| Home | Articles | Allison Brothers: New York City Cabinetmakers |

|

|

|

|

n the early nineteenth century, new york city flourished, becoming the major cosmopolitan center that it is today. Both reacting from and contributing to the surge in productivity, furniture design and output overtook the rival city of Philadelphia. Active among the city’s cabinetmakers during this time were the brothers Michael (1773–1855) and Richard (1780–1825) Allison.1 n the early nineteenth century, new york city flourished, becoming the major cosmopolitan center that it is today. Both reacting from and contributing to the surge in productivity, furniture design and output overtook the rival city of Philadelphia. Active among the city’s cabinetmakers during this time were the brothers Michael (1773–1855) and Richard (1780–1825) Allison.1

|

|

|

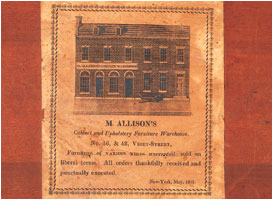

Fig. 1: Paper label of Michael Allison’s cabinet warehouse, 46 and 48 Vesey Street, New York City, dated May 1817.

|

Contemporaries of Duncan Phyfe (1768–1854) and Charles Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819), Michael and Richard both worked at various locations on Vesey Street, only doors away from each other [Fig. 1]. Michael’s career spanned half a century from 1800 to 1847, while Richard worked from 1806 to 1813, abandoning his trade to become a grocer. Richard’s furniture was in the federal style, while Michael made furniture in the various styles popular during his long career, including the federal, classical, and late classical styles.

The furniture made by Michael and Richard Allison is quite distinctive, and because they both religiously labeled their furniture, it is probably better documented than that of any other New York cabinetmaker.3 The New York State Museum in Albany has nine labeled pieces by Michael and three by Richard. The following article is based on the study and comparison of these objects.2

Chests of Drawers: Michael Allison

The first chests of drawers made by Michael Allison are all very similar [Fig. 2]. Following the format commonly found on New York furniture between 1800 and 1815, the flat facade is arranged with graduated drawers surmounted by a large drawer, all above a hollow-centered serpentine skirt terminating in French feet.

Michael Allison’s chests from this period are distinctive, however, in that he outlined the drawer fronts with stringing at the edge and with hollow-cornered stringing within. The large top drawer has a distinctive center horizontal ellipse of crotch mahogany veneer outlined by triple stringing.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Chest of drawers labeled by Michael Allison (1773–1855), New York City, ca. 1800. Mahogany, pine, tulip poplar, mahogany and satinwood veneers. H. 46, W. 46, D. 22 inches. Courtesy, New York State Museum.

|

At both ends of the ellipse he placed two diamond-shaped satinwood veneers set with vertical ellipses of dark holly background and rosebud inlay. A chest of drawers at Boscobel, labeled by Michael Allison, displays the diamond-shaped satinwood veneers without the rosebuds. Sometimes inlaid eagles decorate the diamond-shaped panels.

Chests of Drawers: Richard Allison

As with Michael Allison, the known chests of drawers by his brother, Richard, are also very distinctive [Fig. 3]. Richard also favored the New York hollow-center serpentine skirt with French feet and the graduated drawers with the deep drawer at the top. Richard, however, surmounted the deep top drawer with a pair of small drawers. The designs of the deep drawer on his chests are just as characteristic as his brother Michael’s designs. The flame-grained mahogany veneers on the deep top drawer consist of a pair of rectangles with astragal ends or in some cases a pair of hollow-cornered rectangles.6

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Chest of drawers labeled by Richard Allison (1780–1825), New York City, ca. 1810. Mahogany, pine, tulip poplar, mahogany veneer.

H. 46, W. 45, D. 20 1/2 inches. Courtesy, New York State Museum. |

Pembroke Tables

Both Michael and Richard Allison made some very fine furniture, but like many other New York cabinetmakers, they also made less expensive, more practical furniture. One of the most popular furniture forms in Federal New York was the Pembroke table. These small drop-leaf tables could be used for a variety of purposes, from breakfast to writing tables.

Both brothers made such tables. The mahogany examples illustrated here [Figs. 4, 5] are rather basic but bear paper labels advertising that Michael Allison made one (square leaves) and Richard Allison the other (rounded leaves).7 A fancier Pembroke table in the museum’s collection by Michael Allison has rope-turned legs and clipped corners.

Sideboards

Both Michael and Richard Allison made sideboards, a new furniture form for the federal period. Since Richard’s career was so brief (w. 1806-1813) most of the furniture that he made reflected the Sheraton taste popular during his working years. The museum’s mahogany two-pedestal, bow-front sideboard made by Richard Allison [Fig. 6] has flanking deep cupboard doors inlaid with Gothic arches.8 It stands on typical Sheraton reeded, round-turned tapered legs.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Pembroke table labeled by Michael Allison (1773–1855), New York City, ca. 1810. Mahogany, pine, and tulip poplar. H. 27 3/4, W. 3 11/2,

L. 22, 41 inches, open. Courtesy, New York State Museum; lent by Wunsch Americana Foundation, Inc. |

An inscription on the bottom of the top right drawer reads, “Made by R. Allison, N. York, cost 67$ [sic], July 1810.” A later inscription states that the sideboard was made for Capt. Lieut. Peter Taubman of Tappan Grost, Piermont, New York.9

Michael Allison, who outlived his brother, went on to make furniture in the newer forms of the New York classical style. A large sideboard [Fig. 7] features the exuberantly carved paw feet that proved so popular in the 1820s.10

Card Tables

One of the most elegant and accomplished pieces of furniture associated with Michael Allison does not bear a label [Fig. 8]. This card table illustrates the finely carved New York classical style of the second and third decades of the nineteenth century. It can be attributed to Michael Allison on the basis of its relationship to a labeled Allison desk and worktable in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.11 The most striking resemblance is with the carved eagle-head-shaped feet and the acanthus leaf carving on the legs.

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Pembroke table labeled by Richard Allison (1780–1825), New York City, ca. 1810. Mahogany, pine, tulip poplar, and mahogany veneer. H. 283/4,

W. 31, L. 17 1/4, 33 7/8 inches, open. Courtesy, New York State Museum; lent by Wunsch Americana Foundation, Inc.

|

Pillar-and-Scroll Furniture

Finally, in the 1830s and 1840s Michael Allison worked in yet another popular furniture style, that of the late classical style made popular by Joseph Meeks and Sons of New York City (w. 1829–1836). Influenced by the French Restoration, this simple veneered and uncarved furniture was embellished with pillars (in this instance columns) and scrolls, hence the descriptive term. An important aspect of the embellishment is the matched crotch mahogany veneer. The chest of drawers [Fig. 9] in the museum’s collection bearing Michael Allison’s label dated 1831, is typical of late classical furniture, more generic in appearance than his earlier work.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Sideboard labeled by Richard Allison (1780–1825), New York City, 1810. Mahogany, pine, tulip poplar, and mahogany veneer. H. 51 1/2,

W. 68 1/2, D. 23 1/2 inches. Courtesy, New York State Museum; lent by Wunsch Americana Foundation, Inc.

|

The Allison brothers were not so much trendsetters as products of their time and occupation.12 They, like most New York City cabinetmakers, were influenced by their peers, customers’ desires, and by the furniture design books popular at the time. Michael and Richard Allison’s habit of consistently labeling their furniture leaves a well-documented legacy of their craft.

Much of the New York State Museum’s Allison furniture is currently featured in an exhibit on New York decorative arts entitled, Treasures from the Wunsch Americana Foundation, on exhibit through March of 2002.

John L. Scherer is associate curator of decorative arts at the New York State Museum in Albany.

He has curated numerous exhibits relating to New York furniture and decorative arts and has published extensively on the topic. He lectures on decorative arts, and teaches a graduate course on material culture at the State University of New York at Albany.

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Sideboard labeled by Michael Allison (1773–1855), New York City, ca. 1825. Mahogany, pine, tulip poplar, and mahogany veneer. H. 59, W. 61, D 26 inches. Courtesy, New York State Museum; lent by Wunsch Americana Foundation, Inc.

|

1 Michael and Richard Allison grew up in Haverstraw, Rockland County, New York, where their father, Captain Joseph Allison (1722–1796), had a large farm. They were the sons of a second marriage to Elsie Parsels (1751–1815). Michael was the third son, and Richard the fifth. Michael, who never married, moved to New York City and by 1800 began his career as a cabinetmaker at 42 Vesey Street. Richard followed shortly thereafter, setting up his shop at 201 Greenwich Street in 1806, but moving to Vesey Street by 1807. He married Eliza Ruckel (1785–1870). See Allison Leonard Morrison, The History of the Alison or Allison Family In Europe and America 1135–1893 (Boston, Mass: Damrell & Upham, 1893), pp. 253–54, 260–61; New York City Directories.

2 For additional information on the furniture collection at the New York State Museum, see John L. Scherer, New York Furniture at the New York State Museum (Old Town Alexandria, Virginia: Highland House Publishers, Inc., 1984); and Scherer, New York Furniture: The Federal Period 1788–1825 (Albany, New York: New York State Museum, 1988).

|

|

|

| Fig. 9: Chest of Drawers labeled by Michael Allison (1773–1855), New York City, ca. 1831. Mahogany, pine, tulip poplar, and mahogany veneer. H. 49 3/4, W. 47, D. 23 1/2 inches. Courtesy, New York State Museum. |

3 The fact that Michael Allison regularly changed the style of his labels and the fact that his address on Vesey Street also changed periodically assists in dating his furniture. A number of his paper labels are even dated with the month and year.

4 Several similar chests by Allison with the same top drawer design exist in other collections such as Boscobel, the restored States and Elizabeth Dykeman estate on the Hudson River at Garrison, Westchester County, New York. One of the Boscobel chests of drawers, although unlabeled, is identical to the labeled State Museum example. The chest retains its original rectangular brass back plates stamped with an eagle, thirteen stars, and the national motto, E Pluribus Unum. The backs of the bails are stamped “HJ.” For a discussion on the makers of the “HJ” hardware, see Donald L. Fennimore, “Brass Hardware on American Furniture, Part II, Stamped Hardware, 1750–1850,” in The Magazine Antiques (July 1991).

5 See Berry B. Tracy and Mary Black, Federal Furniture and Decorative Arts at Boscobel (New York: Boscobel Restoration Inc.,1981), pp. 94–95. Several labeled chests of drawers are known with the eagle motif. A clothes press at Winterthur is attributed to Michael Allison on the basis of the configuration of the top drawer with inlaid eagles veneers. See Charles F. Montgomery, American Federal Furniture (New York: Viking Press, 1966), pp. 440–43.

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Card table attributed to Michael Allison (1773–1855),

New York City, ca. 1820. Mahogany and pine with mahogany veneer. H. 31, W. 38, D. 181/2 inches. Courtesy, New York State Museum; gift of Wunsch Americana Foundation, Inc. |

6 For similar chests of drawers by Richard Allison, see Margo Flannery, “Richard Allison and the New York City Federal Style,” The Magazine Antiques (May, 1973): 995–1001.

7 Each table has an original oval back plate and bail handle on the drawer.

8 The sideboard retains original brass pulls.

9 A closely related sideboard is on exhibit at Boscobel. See Tracy and Black, p. 149.

10 The large dated 1817 paper label [Fig. 1] that illustrates Michael Allison’s cabinetmaking shop and warehouse at 46 and 48 Vesey Street depicts a classical carved sofa on the sidewalk with carved feet.

11 Marshall B. Davidson and Elizabeth Stillinger, The American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, 1985), p.149.

12 Richard Allison died on November 26, 1825, of consumption at the age of 45. He left behind his wife and nine children. His brother retired from cabinetmaking in 1847 a very wealthy man. Michael died at his residence, 46 Vesey Street, New York City, March 25, 1855, and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery. See Morrison,

pp. 253–54, 260–61.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|