|

| Home | Articles | With New Galleries, Milwaukee Becomes a Decorative Arts Hub |

|

|

With the May reopening of the Milwaukee Art Museum’s 13,000-square foot galleries for American arts, the Chipstone Foundation has acquired the two things it lacked: exhibition space and the visitors to go with it. The new venue puts the already formidable Midwest institution squarely in the limelight and may even signal a new direction for decorative arts studies around the country. With the May reopening of the Milwaukee Art Museum’s 13,000-square foot galleries for American arts, the Chipstone Foundation has acquired the two things it lacked: exhibition space and the visitors to go with it. The new venue puts the already formidable Midwest institution squarely in the limelight and may even signal a new direction for decorative arts studies around the country.

Chipstone, the Georgian-style residence of the late department store magnate Stanley Stone and his wife, Polly, was endowed as a foundation in 1966. Filled with American furniture, historical prints, and English ceramics, Chipstone’s biggest obstacle in displaying its collections was the zoning restrictions that prevented the public from touring the Stones’ mansion. In 1995, the Milwaukee Art Museum began a $100 million expansion, culminating in the recent opening of its centerpiece: a dramatic, lakeside pavilion created by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. To coincide with the opening, Chipstone suggested that the two institutions collaborate on the provocative display, which mingles their collections with those of the Layton Art Collection, long housed at the museum.

Chipstone Executive Director and Chief Curator Jonathan Prown, Curator Glenn Adamson, and Charles Hummel Intern Nonie Gadsden worked with Milwaukee Art Museum Curator Jody Clowes on the long-term installation. Two independent scholars, Robert Trent and Ellen Denker, were hired for their expertise in furniture and ceramics—Trent has published widely on the first, Denker on the second—and for their well-deserved reputations as iconoclastic thinkers.

The windowless, refurbished galleries on the ground floor of the 1970s-era wing, which now houses the American collections, were hardly the museum’s most desirable. In the hands of the talented exhibition designer Lou Storey, however, the rooms are revitalized with vivid colors and striking tableau to deliver the team’s clever script.

“We began with the premise that decorative arts exhibits are generally not too thrilling,” Prown explains. “We looked at the traditional ways of interpreting the material and decided that they are often too rigid. Culture doesn’t work that way. It’s softer, more fluid. What we chose is a thematic approach that allows us to explore significant cultural connections rather than specific stylistic variations.”

“The topics quickly emerged as we started to delve,” noted Trent, who settled on two movements in Western design that have persisted in different guises over many centuries: classicism and Orientalism. The galleries devoted to classicism are the most radical. Practically banning the word Chippendale, the curators tossed out standard nomenclature and paired unlikely objects. For instance, a Philadelphia hairy paw-foot side chair made for the Cadwalader family, an icon acquired by Chipstone in 1999 for $1.35 million, is shown with a Belter sofa of a century later. The juxtaposition strikes a parallel between the superabundant naturalism of both pieces while challenging the common institutional bias toward eighteenth-century furniture. Says Trent, “Classicism can be linear and structured, or wild and ornamental. But Mannerist, Baroque, or Rococo, it’s one tradition.” “The topics quickly emerged as we started to delve,” noted Trent, who settled on two movements in Western design that have persisted in different guises over many centuries: classicism and Orientalism. The galleries devoted to classicism are the most radical. Practically banning the word Chippendale, the curators tossed out standard nomenclature and paired unlikely objects. For instance, a Philadelphia hairy paw-foot side chair made for the Cadwalader family, an icon acquired by Chipstone in 1999 for $1.35 million, is shown with a Belter sofa of a century later. The juxtaposition strikes a parallel between the superabundant naturalism of both pieces while challenging the common institutional bias toward eighteenth-century furniture. Says Trent, “Classicism can be linear and structured, or wild and ornamental. But Mannerist, Baroque, or Rococo, it’s one tradition.”

Another part of the exhibit considers evolving strategies of furniture production in America from 1650 to 1850. These more familiar-looking displays combine Chipstone’s outstanding trove of New England furniture by such craftsmen as the Goddards and Townsends of Newport and the Dunlaps of New Hampshire.

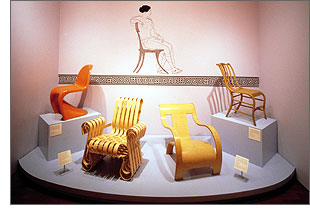

The final themed galleries, grouped as “Icons of Identity,” are in many ways the most novel. “Trivial Pursuits” explores how we literally and figuratively connect to objects and vice versa. In “Sign Language,” the curators consider emblems of identity through makers’ marks on objects as diverse as pottery and silver to portrait paintings and furniture. Another display, “Reinventing the Past,” sorts out different historical strategies we use to interpret the past, for example revivals, which defer to the past, and reinventions, which take inspiration from it.

The new gallery of changing exhibits currently houses Puritan Classicism: Seventeenth-Century Cupboards of Massachusetts. Organized by Robert Trent and Peter Follansbee and on view through September 2, this unprecedented survey represents nearly three decades of research by Trent. From October 5, the gallery will showcase Ivor Noel Hume’s ceramic collection, a recent gift to Chipstone. To coincide with the display, the foundation is publishing Hume’s memoirs, If These Pots Could Talk: Collecting 2000 Years of British Household Pottery.

Prown says Chipstone’s next initiative will be online (www.chipstone.org), and not only anticipates a day when Chipstone’s exhibitions will be virtual and its collections electronically accessible to all, but envisions the Web site as an intellectual gathering spot, open to other contributors. The plan dovetails with his ambition to open the Stones’ Fox Point home as a scholars’ center.

Chipstone’s imaginative leadership has turned what some might see as weakness—geographical remove and lack of exhibition space—into strength. Influential publications, such as the annual journals American Furniture and Ceramics in America, put Chipstone on the map. Now its collaborative galleries for American arts are doing the same for Milwaukee. “With the new Calatrava building, this city will be a destination for art lovers,” says Prown. “Institutionally, Chipstone Foundation is new to the game. Our exhibits need to be excellent, but we have a mandate to be creative. That’s our real strength.”

|

|

|

|

Antiques and Fine Art is the leading site for antique collectors, designers, and enthusiasts of art and antiques. Featuring outstanding inventory for sale from top antiques & art dealers, educational articles on fine and decorative arts, and a calendar listing upcoming antiques shows and fairs.

|