|

| Home | Articles | The Importance of Scale in Framing Works of Art |

|

|

|

|

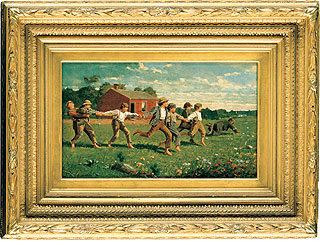

Fig. 1: American period frame, applied composition ornament and gilded, on Snap the Whip by Winslow Homer, 1872. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Christian A. Zabriske, 1950 (50.41); photograph © 1999 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

|

Edouard Manet (French, 1832–1883) said, “Without the proper frame, the artist loses 100 percent.” Many noted artists have shared his sentiments on the importance of finding the proper frame for a painting. In taking up this challenge, the framer contemplates a number of different concerns: the style or design of the frame, the color of the frame—specifically the tonality of the gilded surface or the color of the wood finish—and the scale of the frame; determining the ideal size or width of a frame in proportion to the painting it surrounds is an integral component in framing.

Addressing tonality and design, we can consider the following examples. For one, when framing a tranquil tonalist painting by James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), a subtler green-gold or gray-gold surface is more pleasing than a brightly gilded surface, and more in keeping with Whistler’s concern for the overall tonality of the painting and the frame. If we are framing a vibrant flag painting by Childe Hassam (1859–1935), we know that the personally monogrammed cassetta-style frames (a type of frame with a frieze or center panel and a raised outer and inner edge) that Hassam used on many of his paintings are not only historically appropriate, but aesthetically pleasing.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: American period frame with metal grille, applied composition ornament, and gilt, designed by Stanford White, on Girl with a Lute by Thomas Wilmer Dewing, 1905. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Fine Art, Smithsonian Institution.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3:

Part of frame (see Fig. 2) is masked out.

|

As every painting is unique, it is the individual qualities of each work that we, as framers, examine when searching for a suitable frame. Nowhere is this more evident than when we examine the concept of scale.

The assumption that a small painting takes a narrow frame and a large painting takes a wide frame makes sense in the everyday world. What we are framing, however, is a piece of the artist’s world, created with elements of perspective and proportion that correspond to the artist’s vision. With this in mind, we should not underestimate how our emotional response to a painting is affected by the scale of its frame, as illustrated with the examples by American artists presented here.

Winslow Homer’s (1836–1910) Snap the Whip, dated 1872 and measuring 12" x 20", is surrounded by an American frame, circa 1870–1875 (Fig. 1). Here, the molding is quite wide compared to the size of the painting. The frame design is composed of several rows of crisply rendered ornament that echoes the grass and leaves in the painting. In this case, the frame’s scale and design enhance the expansive feeling of outdoors created by the painting. Homer often specified to his dealer the size and style of the frame he wanted for a painting. For example, he wrote to M. Knoedler & Co. in 1902: “When I saw the picture at your place I was much disappointed by the frame. I did not say anything about it but I noticed that it was an inch & half or two inched [sic] too narrow and not up to the usual mark.” 1

The painting shown here by Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938) is entitled Girl with a Lute and measures 24" x 17 3/4" (Fig. 2). This work is highly characteristic of Dewing’s subtle figure paintings, and it is surrounded by a frame created by architect and designer Stanford White (1853–1906). Dewing was a good friend of White’s and often asked him to design frames for his paintings, sometimes describing the painting or sending White a sketch of it so as to assure an excellent marriage of painting and frame. Notice that in this case the molding width is nearly one-half the width of the painting.

Figure 3 illustrates the same painting and frame with approximately two-thirds of the frame covered up. With a narrower molding, the figure appears somewhat closed-in and the fact that her instrument extends to the very edge of the canvas becomes more noticeable. The figure seems isolated in a small room, and a feeling of introspection is conveyed.

In Figure 2, however, the wider molding of the frame functions as an extension of the room, making the figure look less closed-in. The overall effect is one of energy radiating out from the painting, possibly conjuring for the viewer a sense of the music she is playing or her feeling about the music.

|

|

|

Fig. 4: American period frame, carved and gilded, ca. 1910, on Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney by Robert Henri, 1916. Courtesy of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Flora Whitney Miller (86.70.3); photograph © 2001 Whitney Museum of American Art.

|

Dewing’s Girl with a Lute is a relatively small painting for which White designed a very wide frame molding; yet this was not out of a general preference for wide moldings on the part of the designer. For instance, White wrote to Abbott Thayer (1849–1921), another one of his artist friends for whom he often designed frames, regarding Thayer’s painting Winged Figure, which measures 90 1/4" x 59 3/4": “The picture, in a certain way, is very difficult to frame for the reason that it is a formal and posing picture and would of course stand in a very heavy architectural frame. At the same time a large picture always looks best, I think, with a narrow frame, and I understand that it is your view also.” 2 White’s description of the painting as “difficult to frame” implies that opinions on scale can vary depending on the feeling of the painting—in this case “formal and posing”—rather than the actual size of the canvas.

A case in which a narrower frame complements a large painting is illustrated with Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney by Ashcan School artist Robert Henri (1865–1929), shown here in a lovely carved and gilded frame, circa 1910 (Fig. 4). The painting, dated 1910, measures 52" x 72" and is surrounded by a comparatively narrow molding. As in Dewing’s Girl with a Lute, the figure in the painting extends almost to the edge of the canvas. In this case, the closed-in feeling created by the narrow molding gives the viewer a sense of intimacy that harmonizes with the subject’s relaxed posture. The simple and elongated design of the frame complements her long, slender physique.

If we heed Thomas Cole’s (1801–1848) claim that “the frame is the soul of the painting,” then we must look to the frame to reflect and reaffirm the individual qualities of the painting it surrounds. To carry this analogy further, when searching for the “proper” frame, one may expect that, like people, every work of art will be different in regard to its needs.

Michele Brangwen is Associate Gallery Director at Eli Wilner & Company Period Frames and Mirrors, NYC. Eli Wilner & Company is proud to announce the release of The Gilded Edge: The Art of the Frame, Edited by Eli Wilner, (Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 2000) hardbound, dust jacket, 204 pages, $60. Available at bookstores and museum shops. Also available on Amazon.com and the Chronicle Books Web site. The Gilded Edge offers an in-depth look at exquisite antique frames made in America over the last two centuries and includes essays by curators and scholars in the field of American art. Michele Brangwen is Associate Gallery Director at Eli Wilner & Company Period Frames and Mirrors, NYC. Eli Wilner & Company is proud to announce the release of The Gilded Edge: The Art of the Frame, Edited by Eli Wilner, (Chronicle Books, San Francisco, 2000) hardbound, dust jacket, 204 pages, $60. Available at bookstores and museum shops. Also available on Amazon.com and the Chronicle Books Web site. The Gilded Edge offers an in-depth look at exquisite antique frames made in America over the last two centuries and includes essays by curators and scholars in the field of American art.

Collectors’ Corner is a regular feature that presents useful information for collectors learning about antiques and fine art.

|

|

- City University of New York, Lloyd and Edith Havens Goodrich, Whitney Museum of American Art Record of the Works of Winslow Homer. Letter to Knoedler & Company, dated 9 November 1902.

- Nina Gray, “Beyond Architecture: The Frame Designs of Stanford White,” lecture (4 December 1991): 17-56. Unpublished transcript in Eli Wilner & Company Archives. Quote from a letter in The New-York Historical Society, Stanford White Papers.

|

|

|

|

|