|

|

|

|

|

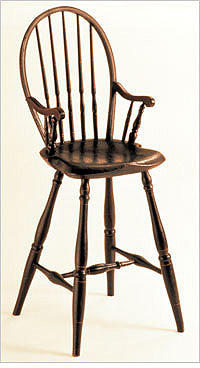

Fig. 1: Fan-back Windsor side chair branded by Elijah Tracy (1766– 1806/07), Lisbon Township, New London County, Connecticut, ca. 1795–1801. Chestnut (seat) with maple and oak. H. 37 1/8, W. 21 3/8 (crest), D. 16 3/4 (seat) in. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum. Tracy was one of a family of chairmakers residing in New London County. A frequent feature of work from this general area is the nodulelike swell of the spindles.

|

The introduction of Windsor side chairs at the close of the Revolutionary War opened a new chapter in the popularity of this vernacular seating style in America. The smaller size and moderate cost of the side chair relative to the breadth and expense of the armchair patterns in the Windsor furniture market encouraged consumers to purchase the new seating form.1

The fan back was the first armless Windsor to enter the consumer market (Fig. 1). The new pattern, named for its splayed back with extended shaped crest, was introduced in the late 1770s in Philadelphia, the birthplace of the American Windsor and the principal center of the craft in America until about 1810. As was the case for most Windsors produced in America before the first decade of the nineteenth century, the general source of inspiration for the construction and pattern was Great Britain. American Windsors differ, however, in both their styling and selection of woods. Most distinctive is the character of the baluster-style leg turnings, the prototype for which was the turned work on Delaware Valley slat-back chairs. The fan-back design also features these turnings in the rear posts of the back with altered proportions.

Placement of Windsors in a household varied, but records generally indicate that they were used extensively in the dining room, or second parlor. The term dining was linked with the Windsor side chair almost from its introduction. As early as October 1779, Joseph Henzey, a prominent Philadelphia chairmaker, billed local merchant Levi Hollingsworth for “3 Dozen dining Windsor Chairs,” probably for retail in the region of the upper Chesapeake Bay.2 Because of their availability and affordability, Windsors were often ordered or purchased in sets suitable for use in dining, six being the usual number.

|

|

|

|

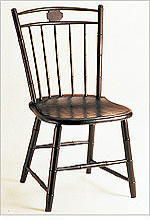

Fig. 2: Bow-back Windsor side chair, Rhode Island, 1790–1795. White pine (seat) with maple and ash. H. 37, W. 16 (seat), D. 16 5/8 (seat) in. Private collection; photography courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

|

In general, families were large in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the narrow dimension of the Windsor side chair permitted greater seating capacity at the dining table. The Windsor also was a practical choice. Its wooden seat did not require frequent replacement, as did rush-bottom seating, and there were no cloth covers to become soiled with food and drink; occasionally stuffed-seated Windsors were produced, but these were intended for other rooms, particularly the formal parlor.

About 1785, less than a decade after Philadelphia craftsmen first produced the fan-back chair, artisans of the city introduced a round-back side chair called a bow-back Windsor. In the expanding postwar American economy, craftsmen in other areas quickly imitated the pattern, introducing subtleties of design reflecting local interpretation. The Rhode Island chair shown in Figure 2 has distinctive, swelled and long-tipped feet sometimes associated with area work. The use of bracing spindles anchored in a rear extension of the seat as a strengthening device was an optional feature available in several regions. During the 1790s the bow-back Windsor soared to popularity as a dining chair, in part because the “locking horns” problem of the fan-back chair was eliminated with the round-back design.

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Advertisement of Ebenezer Stone, Independent Chronicle (Boston), April 20, 1786.

|

Ebenezer Stone’s Boston advertisement of April 1786, with its woodcut illustration (Fig. 3), indicates how quickly the round-back Windsor introduced in Philadelphia was assimilated into the production of other regions. It is notable that Philadelphia work was the standard measure to which craftsmen compared their products. It also speaks, both in visual and descriptive terms, to the popularity and affordability of the Windsor side chair. As indicated, green was the common color for Windsors through the 1780s, a hold over from their initial use as garden furniture, an example of which Stone advertises. His location near the waterfront was convenient for taking advantage of the coastal trade, both for quick transmission of the latest styles and for dissemination of large numbers of his Windsors to other ports.

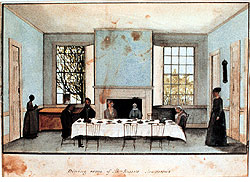

Although the view of the Tiverton, Rhode Island, dining room of Dr. Whitridge (Fig. 4) was painted by Joseph S. Russell in the nineteenth century, it depicts a scene familiar in the 1790s, when the bow-back Windsor was the common seat for dining.3 The table has been opened and laid for breakfast, but between meals it was closed and placed against the wall in the manner of the chairs, leaving the center of the room open as was done into the early nineteenth century. In Connecticut, a contemporary of Whitridge, Dr.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Dining Room of Dr. Whitridge (Tiverton, Rhode Island) by Joseph Shoemaker Russell (1795–1860), ca. 1848–1853, depicting scene of 1814–1815. Watercolor on paper. H. 7 1/16, W. 9 1/2 in. Courtesy of Old Dartmouth Historical Society—New Bedford Whaling Museum.

|

Samuel Lee, also furnished his dining parlor with bow-back Windsors. His inventory reveals that he owned yellow-painted side chairs purchased in the 1790s from Amos Denison Allen, a member of the Tracy family of chairmakers.4

Complementing the Windsor side chair at the dining table in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was the child’s Windsor highchair, known as a “child’s dining chair” (Fig. 5). Designed in this period without a feeding tray or footrest, the chair was drawn up to the table for the child to join other family members at mealtime. When the chair was used away from the table, the child was secured with a sash around the waist that was knotted behind the spindles. Figure 5 is a distinctive example, with its eighteenth-century turned work, baluster-embellished spindles, balloon-style bow, and varnished mahogany arms.5

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Child’s bow-back Windsor highchair, Rhode Island, 1795–1800. White pine (seat) with ash, maple, hickory, and mahogany (arms). H. 35 3/8, W. 12 3/4 (arms), D. 12 3/4 (seat) in. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

|

At the turn of the nineteenth century round-back styles gave way to the popular square-back dining chair available in a variety of crest designs. One was the double-bow pattern (the “bows” curved laterally) centering a small tablet of ornamental profile (Fig. 6). The illustrated example was made by Jared Chesnut at his shop in Wilmington on the Delaware River. The pattern, which was introduced in Philadelphia, was made throughout the Delaware Valley, including western New Jersey and Delaware, and its impact was into New England. Originally, the simulated bamboo work, an innovation of the late eighteenth century, was “penciled” in the grooves with paint of contrasting color with that of the ground, and floral-sprigged or other painted ornament embellished the crest tablet.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Square-back Windsor side chair branded by Jared Chesnut (w. 1800–1832), Wilmington, Delaware, ca. 1804–1810. Yellow poplar (seat) with maple, walnut, oak, and hickory. H. 34, W. 18 1/4 (crest), D. 16 1/4 (seat) in. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

|

Chairs similar to that in Figure 6 provided the seating furniture in the dining room of Abraham Russell of New Bedford, Massachusetts, in the early nineteenth century (Fig. 7). The scene reflects Joseph S. Russell’s boyhood memory of his parent’s home. As Philadelphia was still considered the fashionable center for Windsor chairs, it is entirely likely that the chairs were obtained directly from that location, particularly given New Bedford’s maritime orientation and access to trade. The bond is further strengthened by reason of Mrs. Russell’s Philadelphia roots and the strong ties between Quaker families in the two communities. The austerity of the scene is a reminder that pre-Victorian interiors, especially those outside large urban centers, were often plain with little embellishment, providing a setting that was completely compatible with the basic structure of the Windsor.

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Dining Room of Abraham Russell (New Bedford, Massachusetts) by Joseph Shoemaker Russell (1795–1860), ca. 1848–1853, depicting scene of 1810–1814. Watercolor on paper. H. 5 1/2, W. 8 7/8 in. Courtesy of Old Dartmouth Historical Society—New Bedford Whaling Museum.

|

Handcrafted Windsor side chairs with square backs and varied crest patterns remained popular furnishings for the American dining room through the mid-nineteenth century. By then, inexpensive machine-made furniture was becoming the national norm for families of moderate means. Rather than chairs, table, sideboard, and other dining room furnishings reflecting an assemblage of design, dining room suites were readily available through large furniture emporiums, displacing the local chairmaker’s place in the new industrial marketplace—somewhat ironic given that Windsor chairs were among the first furniture forms suited to assembly-line techniques.

Nancy Goyne Evans is an independent furniture historian and former research fellow of the Winterthur Museum. She has written two books on Windsor furniture, American Windsor Chairs (1996) and American Windsor Furniture: Specialized Forms (1997). She is a graduate of the Winterthur Program in Early American Culture and a faculty member of Sotheby’s American Arts Course.

|

|

- A comprehensive discussion of Windsor furniture can be found in Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Chairs (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1996).

- Joseph Henzey bill to Levi Hollingsworth, October 18, 1779, Hollingsworth Manuscripts, Business Papers VII, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- A discussion of the artist Russell and a representative selection of his work can be found in Sotheby’s, The Bertram K. Little and Nina Fletcher Little Collection, Part II, New York, October 21 and 22, 1994, sale no. 6612, lots 669-673, 866-870.

- Dr. Samuel Lee probate inventory, 1815, Windham Co., Connecticut, Genealogical Section, Connecticut State Library, Hartford; Amos Denison Allen memorandum book, 1796–1803, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford.

- A comprehensive discussion of children’s furniture and other specialized Windsor forms can be found in Nancy Goyne Evans, American Windsor Furniture: Specialized Forms (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1997).

|

|

|