|

| Home | Articles | Blue-and-White English Porcelain: Delicacies for the Table |

|

|

|

|

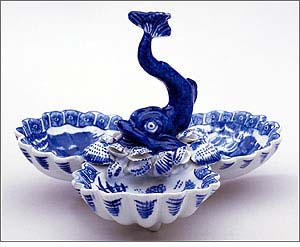

Fig. 1: Soft-paste porcelain triple scallop-shell-molded centerpiece, painted in underglaze blue in the “Desirable Residence” pattern, Bow, ca. 1760–1765. H. (approx.) 7".

|

The fascination with blue-and-white porcelain imported from the Orient spurred manufacturers in England to produce their own white wares with cobalt blue decoration. By the mid-sixteenth century, British earthenware producers harnessed the technology of tin glazes to imitate the “wondrous” porcelains from the East. Although potters were able to closely mimic decorative treatments, they could not re-create the delicately rendered motifs and thin, translucent bodies characteristic of Chinese porcelain.

The race among English ceramic manufacturers to formulate a recipe and find the ingredients necessary to produce porcelain reached a zenith in the mid-eighteenth-century. Three factories—Chelsea, Worcester, and Derby—led the way, producing a soft-paste porcelain body that, while closer in appearance, still did not achieve the qualities of true hard-paste porcelain. By 1768, chemist William Cookworthy patented a formula for true hard-paste porcelain. He established a factory in Plymouth (1768–1770) and started production. While England’s elite could now acquire true English porcelain, manufacture was limited, vying with locally made soft-paste porcelain and true porcelain imported from China and the continent.

Chinese designs continued to influence the decoration on porcelains. The cobalt blue on English wares from this period range in intensity from a blackish blue to a grayish tint depending on the impurities of the cobalt ore and variations in the kiln temperature. The wares from myriad factories, the pattern motifs, and color variations, combined with the occasional designs based on silver shapes, provide rich material from which today’s connoisseurs on both sides of the Atlantic may choose when forming collections.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: (Clockwise from lower left): Soft-paste porcelain a) Egg draining spoon, Derby, ca. 1770; b & d) Two wine tasters, Derby, ca. 1765–1775; c) Leaf-shaped pickle dish, Derby, ca. 1770; d) Asparagus tray, Derby, ca. 1775. D. 3". |

Among the most popular items that intrigue collectors of English blue-and-white porcelain are tablewares. Standard forms, such as tureens and tea sets, are usually the first items to enter a collection, while the more obsolete objects can present a challenge to find. Often an object’s name provides a sense of delight and curiosity about its original purpose—patty pans, potted meat dishes, waste bowls—while others have a familiar ring due to their continued use today—pickle dishes, egg cups, tea pots. The original use for many obscure porcelain objects was to hold some salt, spice, sweet, or savory substance, often meant to disguise the true odor or taste of food that was no longer fresh. Even water was often fouled, and therefore people in eighteenth-century England drank beer, cider, and punch with far greater frequency than water. This explains in part the eagerness with which all strata of society adapted to tea and coffee drinking, which both rely on boiled and thus purified water.

Salt dishes represent a large segment of period containers specific to dining. While many examples were nondescript, the finer receptacles presented salt in a dramatic fashion. At the height of the rococo period, in which designs frequently emulated natural forms, salt dishes were often made to represent scallop shells, of which examples from Limehouse, Bow, Worcester, Caughley, Lowestoft, and Derby are known. More elaborate designs, linking several scallop shells at the bases to an armature of realistically modeled periwinkles and coral, exhibit the height of rococo fashion.1 Among the most glorious salts are those made at Bow, circa 1760–1765. The example in Figure 1 depicts three conjoined scallop-shell dishes with a fanciful dolphin rising among a profusion of realistically modeled mussels, whelks, and periwinkles. With the dish interiors embellished with cell-and-diaper border around fashionable Chinese-style landscapes, this tour-de-force unites two of the main eighteenth-century decorative currents, the rococo and chinoiserie. It would have made a splendid adornment to a richly set table in its day.

|

|

|

Fig. 3: Two soft-paste scallop-shell-molded pickle dishes, painted in underglaze blue with a Chinese vase issuing feathers before a scroll, with ribbon feather motifs at the borders, Limehouse, ca. 1746–1748. L. 3 3/4", W. 3".

|

Although serving dishes are anything but obsolete, the use of creamboats (Fig. 5a) and sauceboats has in many cases become ceremonial. Some of the earliest examples of English porcelain sauceboats were those made at Limehouse before 1750; these receptacles exist in small numbers. The most prolific manufacturer of sauceboats was Worcester. Sparrow-beak cream pitchers, which equate to the aluminum creamers found in diners today, were made in great quantities from the mid-1760s until the 1790s by various firms. Examples from William Littler’s factory at Longton Hall were the largest creamers made, while a miniature creamer from the Liverpool factory of William Chaffers is an extraordinary rarity at less than 1 1/2 inches high.

Some porcelain tablewares are best appreciated with an understanding of the importance placed on the display of fine food in the latter half of the eighteenth century in England. Take, for instance, the obsolete but intriguing asparagus tray (Fig. 2d), which prevented individual spears from rolling loosely about the plate. This is a perfect “quizzler” item for today’s students of connoisseurship, as very few people would guess that a small, tapering, fan-form object framed by two undulating low “walls” was designed to present asparagus. Students of history will appreciate how exotic this vegetable was at the time and how Francophile the English aristocracy was, and know that this tiny item represents both a cultural and a sociological moment in time. Derby seems to have been the most prolific producer of such items, although Caughley and Worcester also made the form.

|

|

Fig. 4: (left to right): Soft-paste porcelain a) Patty pan painted in underglaze blue with a trellis and foliate border surrounding a butterfly to the center interior, workman’s numeral 3 to footrim, Lowestoft, ca. 1770. Diam. 4 3/8"; b) Vein-molded pickle leaf dish painted in underglaze blue with husk border and flowering peony all over body, workman’s numeral 6 to footrim, Lowestoft, ca. 1770. L. 4".

|

Popular after 1750, pickle dishes contained savory, chutney-style relishes that would have been served to each individual at the dining table. Among the forms designed for pickles were scallop shells (Fig. 3), molded with a shallower bowl than similarly designed salts.The delicate leaf forms of some pickle dishes (Figs. 2c, 4b) with lifelike veining and stems, were made in sizes as small as 3 inches and as large as 5 inches. Larger leaf-shaped dishes were also frequently used for serving sweetmeats (candied fruits and nuts). Though Worcester seems to have been the largest producer of these dishes, collectors often seek examples from the smaller factories such as Lowestoft. Patty pans (Fig. 4a) were also intended for individual dinner guests. These containers were used to present French-style pâtés, baked meat pastries, or savory tarts. Potted meat dishes were used in a similar fashion. There is discussion as to whether food was actually baked in these dishes or if they were only meant for presentation. The popularity of serving potted meats resulted in the heavy use and breakage of these dishes, which may explain the relative rarity of the form. Examples made at Bow and Lowestoft are rarer than those made at Worcester.

|

|

Fig. 5: (left to right): Hard-paste porcelain a) Molded creamboat, Plymouth, ca. 1769–1770. W. 4 5/8"; b) Centerpiece to a sweetmeat dish, Plymouth, ca. 1769. W. 4".

|

The eighteenth-century English elite considered sweetmeats a necessary accompaniment to the fashionably-set dessert table. Among the ways to serve these little delicacies were in fan-form dishes arranged around a central hexagonal or pentagonal dish, all set within a star-shaped or circular wooden base. Today, sophisticated collectors work to reassemble complex arrangements of these often-separated dishes (Fig. 5b). A particularly fine example was made at Richard Cookworthy’s factory in Plymouth. As noted, Plymouth was one of the few English manufacturers that produced hard-paste porcelains in the manner and tradition of the porcelains from Meissen in Germany and several other continental factories. Unlike their continental competitors, the English received no financial backing from nobility, and for this reason many companies were short-lived. Cookworthy, for example, could never raise enough funds to keep the kilns firing, and few pieces of Plymouth survive today. The sweetmeat dishes made at Plymouth copy prototypes made at the St. Cloud factory in France—but the eighteenth-century French example is soft-paste, and the English example is hard-paste porcelain.

English blue-and-white porcelain decorated in the Chinese manner realized its heyday around 1780, as less expensive transfer-printed creamwares and pearlwares flooded the market. The lower end of the socio-economic scale would be happily satisfied with these dishes on their table, while wealthier patrons sought ever more fanciful shapes decorated with new, rich ground colors and gilding styles. That notwithstanding, the lustrous appeal of the early blue-and-white porcelains has intrigued collectors since they were made.

All photographs courtesy of Fenichell Basmajian.

Jill Weitzman Fenichell is an antique ceramics dealer and partner of Fenichell-Basmajian Antiques, New York. She lectures and writes frequently on European ceramics.

|

|

|

- This form was also used for sweetmeats, depending on the dining situation.

|

|

|