|

| Home | Articles | Decorating the Avery Coonley House: Frank Lloyd Wright and George... |

|

|

|

|

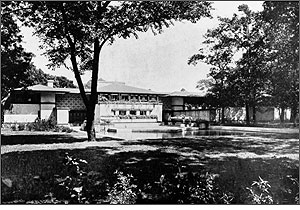

Fig. 1: Garden façade of Coonley house, from Ausgeführte Bauten, 1911. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum.

|

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) was deeply committed to the idea that a house and its furnishings should be both an artwork in which to live and a living work of art inspired by nature. Genius though he undeniably was, Wright alone could not accomplish his grandiose vision for a holistic architectural environment that integrated site, building, and interior decoration. One of the most important and enduring of his collaborators during the first two decades of the twentieth century was George Mann Niedecken (1878–1945), a Milwaukeean who styled himself an interior architect.1 Niedecken’s reputation rests on the customized decorative arts he devised for Wright’s clients during the heady years when the Prairie style revolutionized the domestic landscape of the Midwest.

Trained in decorative design at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and in Paris by art nouveau artist Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), Niedecken supplied murals, textiles, metalwork, and furniture for a dozen of Wright’s house commissions during the fifteen years that comprised the hey-day of the Prairie era, circa 1902–1917. Niedecken first worked for Wright in his Oak Park studio as a delineator of presentation drawings and a mural artist before setting up his own interior design firm in 1907 with his brother-in-law, a businessman named John Walbridge.

|

|

|

|

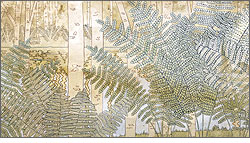

Fig. 2: Detail study for living room mural by G. M. Niedecken, 1908. Ink and watercolor on cream wove paper. 8 1/2 x 15 inches. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum.

|

Niedecken functioned as an independent contractor to Wright, issuing invoices on his own company letterhead for services rendered to the architect’s clients. Those services ranged from conceptualizing decorative arts—sometimes alone, sometimes in concert with Wright—to producing color charts and scaled working drawings, as well as artistic renderings of suggested room decorations, to overseeing subcontractors who executed or installed the special-order Wrightian furnishings. The two men complemented each other’s expertise: Wright’s talents lay in the organization and sculpting of space, whereas Niedecken was gifted in graphic design, color harmony, and flat-pattern mural painting.

Wright entrusted Niedecken with significant authority, autonomy, and visibility in the ambitious and complex Prairie-style estate commissioned in 1907 by the Avery Coonley family of Riverside, Illinois [Fig. 1]. By the time the main residence was finally furnished in 1910, Niedecken had designed and painted a stylized birch-and-fern diptych mural, which sounded the keynote for the earth colors and plant motifs utilized inside and outside the dwelling [Fig. 2]; he had supervised the creation of carpets and curtains, plus furniture and accompanying upholstery, embroidered cushions, and spreads [Fig. 3]; and he had selected complementary art pottery and picture frames.

|

|

|

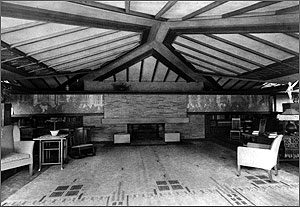

Fig. 3: Living room of Coonley house, photographed by Henry Fuermann, ca. 1910. Gelatin silver photograph. 6 3/8 x 9 1/4 inches. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum.

|

The Coonleys were Wright’s first patrons to authorize a custom carpet scheme for their entire house. Wright’s studio designed the living room and adjacent hall carpets, evoking a forest floor dotted with leaves, small flowering plants, and splashes of sunlight filtering through a canopy of tree branches [Fig. 3]. The floor coverings also echoed the tile mosaic on the exterior of the house and the gridded designs found in the art-glass windows. The bedroom carpets, though, were conceived by Niedecken.

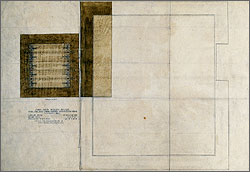

Textiles for the bedroom wing had not yet been worked out when Wright disbanded his studio and departed for a year in Europe (1909–1910).2 Comparison of Niedecken’s concepts for these private areas with Wright’s for the public areas of the house illustrates a kindred manipulation of a square-and-rectangle grid derived from the art-glass and wall tiles. The master bedroom carpet scheme featured an intricate inner-border design, similar to a mosaic; the repeat consists of an assemblage of concentric squares and rectangles with trailing “vines” of pendant squares [Fig. 4]. The pattern seems a distillation of the tiled façade and vine-filled planter boxes punctuating the raised, L-shaped corridor of sleeping chambers [Fig. 5].

|

|

|

|

Fig. 4: Design for master bedroom rugs by G. M. Niedecken, 1909–1910. Pencil and watercolor on tracing paper. 19 x 27 inches. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum.

|

Niedecken’s gemlike dots of color arrayed against plain, neutral grounds paralleled Wright’s use of colored squares to enliven the mostly clear-glass casement windows that wrapped around his Prairie houses. Niedecken alluded to the fundamental idea of casements aligned in a series not only in his carpets but also in the bedroom furniture he originated for the Coonleys. His rear guest room desk, for example, features four side-by-side hinged wooden panels opening outward [Fig. 6]. Indeed, the design of the desk rendered in miniature the bedroom wing appended to the main axis of the residence [Fig. 5]. The desk’s heavy, molded base supports columnar legs sporting paired horizontal strip moldings reminiscent of the wood banding on Wright’s stout architectural piers; the gaping hollow beneath the desk’s writing surface mimicks the driveway passage under the block of sleeping rooms; the emphatic overhang of the tabletop reiterates the wide sheltering eaves and terrace extensions of the dwelling’s exterior; and pyramidal light shades, which jut above the flat top of the desk, mirror the slightly gabled roofline pierced by the rectangular chimney stacks.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Master bedroom and guest room wing of Coonley house, from Ausgeführte Bauten, 1911. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum. |

Comfortable, serviceable chairs such as rockers and upholstered pieces were one of Niedecken’s strengths and, frankly, one of Wright’s weaknesses. Hence, some of the customized seating furniture created for the Coonleys’ living room while Wright was still resident in Oak Park in 1908–1909 was, in fact, Niedecken-designed. Niedecken dubbed the Coonleys’ allover upholstered armchairs with elegant curved profile and refined tapering legs, “Carpenter-type” chairs [Fig. 3].

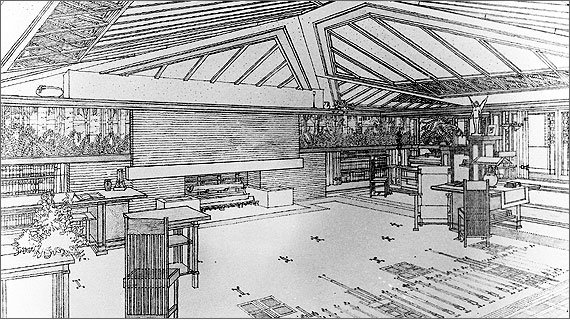

The Carpenter model became a standard item in Prairie-style living rooms furnished by the Niedecken-Walbridge Company during the decade of 1907–1917.3 With a cant to the back of 8 1/2 inches, it was ergonomically proportioned; Niedecken even captioned a prototype side-elevation drawing, “Curve to back makes this chair very comfortable.” Yet only dignified, upright spindle-back chairs and a thronelike wood-panel armchair were illustrated in the Coonley living room perspective Wright submitted, during his 1910 European sojourn, for the Survey of his work titled Ausgefürte Bauten und Entwüfe von Frank Lloyd Wright.4 In order to promote an idealized image of his architectonic designs, the architect omitted Niedecken’s custom-embroidered loose cushions for the Coonley’s straight chairs in addition to the Carpenter armchairs and rockers in both the compley upholstered and slip-seat versions.

|

|

|

Fig. 6: Preliminary drawing of rear guest room desk by G. M. Niedecken, ca. 1910. Pencil on kraft paper. 10 7/8 x 8 7/16 inches. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum.

|

Niedecken continued to do work for the Coonley family through 1913, although by the end of 1910 the bulk of the household decorations had been completed. His insight, expertise, and perseverance resulted in a unified decorative scheme that harmonized with Wright’s iconoclastic architecture while satisfying the Coonleys’ domestic urges for comfort, continuity, and at least a modicum of conventionality. Regarding architect-decorator-client relationships, Niedecken wrote in a 1913 article:

The profession of an interior decorator has never received its proper standing in any community; people do not seem to realize that of all professions akin to art, it is, relatively speaking, the most difficult one. To be clear, the man who seriously takes up a profession which carries with it the development of the interior of a house or building must not only be a strong, natural-born designer, must not only have natural taste, but must have a certain knowledge along the other varied lines of art in order to be of any value either to the architect or the layman. In other words, he must be an artist not only at heart, but in fact, with sufficient talent to paint creditable pictures…5

Cheryl Robertson, an independent scholar and museum consultant in Cambridge, MA, specializes in American decorative arts and material culture of the 19th and 20th centuries. She was formerly Curator of Decorative Arts and the Prairie Archives at Milwaukee Art Museum. Her publications include Frank Lloyd Wright and George Mann Niedecken: Prairie School Collaborators (1999) and The Domestic Scene (1897–1927): George M. Niedecken, Interior Architect (1981).

|

|

Fig. 7: Living room of Coonley house, from Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright [Wasmuth Portfolio], 1911. Courtesy of Milwaukee Art Museum.

|

- Niedecken believed the interior architect was different from the ordinary decorator in that he provided customized furnishings following drawings he originated to harmonize with the architect’s building and the surrounding site. See Geo. M. Niedecken, “Relationship of Decorator, Architect, and Client,” Western Architect 19 (May 1913): 44. Niedecken’s student work, professional drawings, office records, and portions of his design library and Japanese print collection are owned by the Milwaukee Art Museum.

- Wright scandalously abandoned his family to pursue a liaison with the wife of a former Oak Park client. Upon his return, Wright did not reopen his studio, but focused on designing Taliesin, a country retreat near Madison, WI, for himself and his lover.

- The Bogks and Allens selected chairs of this sort for their respective homes in Milwaukee and Wichita, both under design by Wright in 1916 and furnished by Niedecken in 1917–1918.

- The Berlin publisher Ernst Wasmuth produced for Wright, in 1910–1911, two vanity publications chronicling the architect’s Prairie-style buildings and interiors. Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe, in two folio volumes, features drawings; whereas the Ausgeführte Bauten, which Wright called a Sonderheft, or special edition, is a small book of photographs and plans. The two-volume monograph was long thought to have been published first—in 1910—followed by the Ausgeführte Bauten in 1911. In reality, the monograph was printed in 1911. A European edition of the Sonderheft appeared in November 1910, but the American edition was not available until a year later.

- Niedecken, “Relationship of Decorator, Architect, and Client,” p. 44.

|

|

|