|

| Home | Articles | Reading the Evidence: The Challenge of Furniture Documentation |

|

Unlike buildings or gravestones, which for the most part remain fixed in position as their makers originally intended, furniture is by definition moveable. Few houses retain their original furnishings intact through the generations as objects are typically dispersed and relocated with the movements of owners, or by sale or inheritance. The printed labels, signatures, stamps, and brands early American furniture makers sometimes applied to their work often provide the only certain means of identifying objects no longer in their original context.

The examples of American furniture that bear some form of identification as to maker, or are documented through surviving sales records, accounts, or the family papers of craftsmen or owners, are relatively few considering the amount of furniture early artisans produced. These documented objects form the foundation for the attribution of larger bodies of related but unmarked pieces, making their proper interpretation all the more important. An examination of furniture from the New Hampshire Historical Society’s collections demonstrates the need for caution in interpreting documentation associated with furniture and in attributing other objects on the basis of such discoveries.

|

|

|

|

Figs. 1, 1a: Desk owned by General John Stark (1728–1822) of Derryfield (now Manchester), New Hampshire, made by John Kimball (1739–1817), 1762. Inscribed, “February/23rd. 1762/ John Kimball.” Maple; pine. H. 43-7/8", W. 35-1/2", D. 18-7/8".

|

|

|

|

Rarely is a maker’s signature as easy to find and read as that pictured here on the back of a slant-front desk (Figs. 1, 1a). In contrast to this boldly painted inscription, others executed in ink, graphite (pencil), or chalk are often practically invisible. Correctly reading what is recorded on a piece of furniture is often the first challenge. Eager researchers have been known to mistake construction marks such as “upper edge” and “bottom” for makers’ names. Unfortunately for scholars and connoisseurs, early furniture makers did not sign the bulk of their work. They are most likely to have signed pieces when they first left apprenticeships (typically around the age of 21), when first in business for themselves, when moving to a new location, or as a form of advertising when sending a piece out of town. In keeping with potentially all of these reasons, the maker of this desk was a 23-year-old joiner from Bradford, Massachusetts, who worked for a short time in Manchester before settling in Concord, New Hampshire.

Most signatures and other marks found on furniture document the owner’s (Figs. 2, 2a) rather than the maker’s identity. During a short period in the early nineteenth century, at least fifty residents in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, are known to have branded their names on their furniture. The practice of branding property for the purpose of identification may have reflected either fear of British invasion or fear of fire. There were several disastrous fires in Portsmouth during the first decades of the century. The branding of property did little to protect it from the flames, but might have helped in sorting and claiming rescued pieces as well as in deterring looting. Although these marks do not identify cabinetmakers per se, the practice of branding greatly expands our knowledge of the types of furniture made and used in New Hampshire’s seaport.

|

|

|

|

Figs. 2, 2a: Light stand owned by Charles Blunt (1768–1823), ship owner and captain, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1770–1800. Mahogany. H. 27-3/4", W. 16-5/8", D. 16-3/8". Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles L. Kaufmann.

|

|

|

|

Until the discovery of Joel Joslyn’s chalk signature inside the upper case (Fig. 3), this high chest was assumed to be the work of the talented rural cabinetmaker Samuel Dunlap, to whom many similar examples have been attributed. Evidence appearing in Dunlap’s account book proves that Joslyn served as his apprentice. At the time, a typical cabinet shop included apprentices learning the trade and journeymen working for the master craftsman while accumulating the wherewithal to set up their own shops. The presence of assistants, several of whom might work on a single object, complicates attributions to the shop’s master. Joslyn may have made part or all of this high chest while working in Dunlap’s shop, in another Henniker shop after Dunlap moved to Salisbury in 1797, or in a shop of his own. Furthermore, when Joslyn later moved to Lebanon, in New Hampshire’s Connecticut Valley, he presumably carried with him the distinctive style and characteristics associated with the work of the Dunlap family, likely combining what he knew with the aesthetic preferences of his new community.

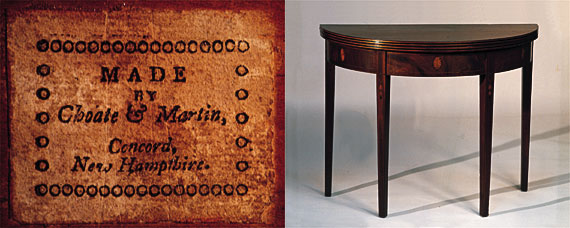

Young craftsmen sometimes moved to inland communities to set up shop where they would face less competition. Often they relocated from town to town before settling down, carrying with them skills, working methods and an aesthetic sense developed elsewhere. Robert Choate and George W. Martin moved to Concord, New Hampshire, from Newburyport and Marblehead, Massachusetts, respectively. The Concord partnership lasted for only two years, after which Choate moved to Orford, New Hampshire, while Martin returned to Essex County, Massachusetts, settling in Salem. Such migrations resulted in similarities among pieces made in widely separated locales. This table (Figs. 4, 4a) bearing Choate and Martin’s Concord label betrays its Essex County roots. The table is remarkably similar to a contemporary example by Samuel and William Fiske of Salem. The table is the earliest New Hampshire example bearing a printed label, usually not found except in or near towns like Concord, large enough to support a printer.

|

|

|

|

Figs. 4, 4a: Card table by Choate and Martin (in partnership 1794–1796), Concord, New Hampshire. Mahogany; mahogany veneer and light and darkwood inlays; pine and birch. H. 28-3/4", W. 35-7/8", D. 17-3/4".

|

|

|

|

Attribution of this sideboard (Fig. 5) to the partnership of Judkins and Senter is based on its remarkable similarity to another, first owned in the Wendell family of Portsmouth and now in the collections of the Strawbery Banke Museum, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. The latter not only bears an inscription by the makers but is documented as well by a surviving bill. The two sideboards are so closely related that their veneers clearly came from the same piece of wood. An attribution this simple and straightforward, however, is extremely unusual. The attributed sideboard, when discovered on the New York antiques market, had lost all trace of its ownership history. A recently discovered photograph in a published genealogy, however, helps identify the piece as most likely once owned by the Hayes family of Berwick, Maine, a short distance from Portsmouth.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5: Sideboard attributed to Judkins and Senter (in partnership 1808–1826), Portsmouth, New Hampshire, ca. 1815. Mahogany, birch, maple, and other woods. H. 42-5/8", W. 71", D. 23-5/8".

|

|

|

|

|

|

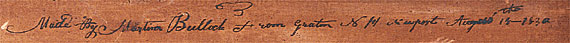

Figs. 6, 6a (at top and above left): Chest of drawers inscribed on reverse: “Made By Martin Bullock from Gra[f]ton NH Newport August the 18 1830.” Mahogany; pine. Purchased with funds donated by the W. N. Banks Foundation. Fig. 7 (at right): Dressing table bearing signature of maker, Martin Bullock (1810–1876), probably Newport, New Hampshire, ca. 1830. White pine and unidentified hardwood.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figs. 8, 8a: Tall clock, movement by Abel Hutchins (1763–1853), Concord, New Hampshire; maker of case unknown, ca. 1810–1820. Cherry, walnut, and mahogany. H. 89-1/2", W. 19-1/2", D. 9-7/8". Gift of Mrs. Ralph Beckett.

|

|

|

|

|

Another factor complicating attribution on the basis of documented examples is that many individual makers and shops displayed tremendous versatility. There is often surprisingly little resemblance among the various products identified as an individual craftsman’s work. Reasons for this include the longevity of many craftsmen and the many stylistic periods in which they worked, as well as their relocation and influences of other craftsmen. Another is that early cabinetmakers took pride in their ability to “ornament to any person’s taste.” They offered to finish a piece either “plain or elegantly,” as the customer desired. This veneered chest (Figs. 6, 6a) and painted dressing table (Fig. 7) are both documented as the work of Newport, New Hampshire, cabinetmaker and decorative painter Martin Bullock. Other than the profile of the splashboard scrolls and unusual curved recess in the top that these pieces share, there is little else to unite them stylistically.

The craftsman whose name appears on the dial (face) of a tall clock was usually not a woodworker but a metalworker, responsible for the clock’s movement or works, either importing them or having a hand in their manufacture. The joiner or cabinetmaker who made the wooden case, would usually, if he marked it at all, attach his label to the backboards inside the lower door or on the inside of the door itself. This example (Figs. 8, 8a), with works by the noted Concord clockmaker Abel Hutchins, is typical in its prominent display of the clockmaker’s name while the maker of the case has been forgotten. Account book entries from the early 1810s show that Hutchins purchased clock cases from a cabinetmaker in Salem, New Hampshire. Corroborating evidence is necessary, therefore, before assuming that a case was made in the town that the inscription on the dial suggests. It was also common practice to purchase a movement from a clockmaker and use it as a timekeeper without a case. Only later, and sometimes after moving to another town, would the owner hire a cabinetmaker to build a case for the clock.

The patterned inlay embellishing federal-period furniture was not necessarily a product of the craftsman whose label an object bears. Concord, New Hampshire, cabinetmaker Levi Bartlett, for example, advertised a supply of “English String and Banding” at his shop. Cabinetmakers who made their own inlay learned this skill from a master whose work their own no doubt resembled, so attribution to a specific cabinetmaker should not depend on similarity of inlay alone. This elaborately veneered chest (Fig. 9) is not documented as to its maker, but has a family history and inscription suggesting it came from Dunbarton, New Hampshire. Family histories are not as dependable a basis for attribution as maker’s marks. This chest, though, relates stylistically to other pieces with histories in the same town. The dropped panel at the center of the skirt and some of the inlay patterns, once considered to indicate a Portsmouth origin, are now known to appear on inland pieces as well.

By the first years of the nineteenth century there was increased coastwise trade. As a result, local cabinetmakers had greater access to patterns from urban centers such as Boston and New York, and, less directly, from London and Paris. New Hampshire cabinetmakers, as this advertisement shows (Fig. 10), were aware of the style trends outside the state. As a result of such influences from afar, certain key pieces of Concord furniture were long attributed to Boston, until surviving bills proved them to be of New Hampshire origin.

As this exercise has hopefully shown, there are many possible interpretations of documentary evidence. Careful analysis of available information enables connoisseurs and scholars to avoid inaccurate conclusions such as can result from too hasty judgement. Connoisseurship is based on accumulated knowledge; it also requires caution and an awareness of the limitations of knowledge. As noted museum professional and teacher Charles Montgomery pointed out, a connoisseur is like a judge gathering and weighing the evidence. So, no matter how exciting it may be to discover a signature or label, remember to take some time for study and contemplation of its full meaning and significance.

Donna-Belle Garvin, formerly curator of the New Hampshire Historical Society’s Museum of New Hampshire History, has served as editor of the Society’s journal, Historical New Hampshire, since 1997.

A reprint of NHHS’s On the Road North of Boston: New Hampshire Taverns and Turnpikes 1700–1900, which she co-authored with James L. Garvin, will be available in Spring 2003.

All items pictured are from the collection of the New Hampshire Historical Society, Concord, New Hampshire. Photography by Bill Finney.

|

|

|

Suggested Reading:

|

|

Garvin, Donna-Belle. “Concord, New Hampshire: A Furniture-Making Capital.” Historical New Hampshire 45 (Spring 1990): 4–87.

—-. “A ‘Neat and Lively Aspect’: Newport, New Hampshire as a Cabinetmaking Center.” Historical New Hampshire 43 (Fall 1988): 202–224.

—-. “Two High Chests of the Dunlap School.” Historical New Hampshire 35 (Summer 1980): 163–185.

—-, James L. Garvin, and John F. Page. Plain & Elegant, Rich & Common: Documented New Hampshire Furniture, 1750–1850. Concord: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1979.

Jobe, Brock, ed. Portsmouth Furniture: Masterworks from the New Hampshire Seacoast. Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1993.

|

|

|