An Introduction to American Sporting Art

|

An Introduction to American Sporting Art

by Stephen B. O'Brien, Jr.

Py the mid-nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution had created an upwardly mobile middle class in America that enjoyed time for leisure pursuits such as hunting and fishing for sport. Concurrently, the technical developments in steam-driven printing presses, machine typesetting, and offset lithography made the mass production of images possible. Through the resulting availability of inexpensive prints, the general public could now decorate their homes with scenes of favorite subjects and pastimes. Sporting activities pictured in wildlife-rich woods offered the romantic appeal of adventure for nineteenth-century urban dwellers: Such escapism continues today, even though the genre of sporting art has changed.

| |

| Fig. 1: Currier & Ives (active, 1857–1907), after Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (English-American, 1819–1905), A Rising Family,1857. Hand-colored lithograph, 22 x 28 inches. |

While enthusiasm for hunting and fishing was on the rise, a counter-movement was also taking hold. This movement, exemplified by the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Cullen Bryant, encouraged Americans to “enter this wild wood and view the haunts of Nature” for spiritual growth. Nature became a teacher of moral lessons. Thus, two popular incentives created a rise in demand for sporting art: recreational pursuits of game and, alternatively, a heightened appreciation of nature’s majestic beauty and spiritual significance.

In a shrewd observation of a ready market, the lithography firm of Currier & Ives took advantage of new advances in offset lithography and began mass-producing prints of the outdoorsman’s life to meet public demand in the 1850s and 1860s. The English-born artist A.F. Tait (1819–1905), a friend of the firm’s founder, Nathaniel Currier, created hundreds of paintings of birds and Adirondack sporting scenes (Fig. 1). Currier & Ives, as well as the firm Goupil & Company of New York, then produced affordable prints based on Tait’s paintings, widely distributing them for twenty-five cents apiece or six for a dollar.

| |

| Fig. 2: Frank W. Benson (American, 1862–1951), Black Ducks. Watercolor on paper, 181/2 x 23 inches. |

By the latter part of the nineteenth century, collecting prints was a widespread American pursuit. In 1895, Charles Scribner’s & Sons commissioned the artist Arthur Burdett Frost (1851–1928) to create hunting scenes for a popular folio on sport titled The Shooting Pictures. Frost, along with Winslow Homer, is considered one of the renowned artists from the Golden Age of Illustration. His work, which chronicled daily life in pastoral New England, appeared in major publications of the day including Harper’s Weekly and Scribner’s.

At the close of the nineteenth century, artists had different objectives in depicting wildlife and the pursuit of game. The genre’s narrative content and illustrative style, intended for popular consumption, was supplanted by a focus on artistic achievement that was aimed at fine art collectors. Hence, after mass-produced prints, the next major progression in American sporting art came about when several accomplished painters, including Frank W. Benson, A. Lassell Ripley, and Ogden Pleissner, turned from the traditional subject matter of the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries—landscapes, portraits, and still lifes—and successfully focused on sporting subjects in watercolor and oil.

A friend once described Frank W. Benson (1862–1951) as “a big man in every way—hale, hearty and strong—a hundred ducks falling to his gun was a common occurrence.” The description is in tune with an artist whose first love was the sporting life and who, as a boy, both hunted and dreamed of becoming an ornithological illustrator. After attending the Boston Museum School and L’Academie Julian, the artist became known as America’s “Most Medalled Painter.” By the early 1890s, Benson had garnered both fame and fortune from his exquisite impressionistic oils of women and children painted en plein air.

| |

| Fig. 3: Aiden Lassell Ripley (American, 1896–1969), Grouse Shooting. Signed and dated A. Lassell Ripley, 1946. Watercolor on paper, 18 x 22 3/4 inches. Provenance: Commissioned by Field & Stream, 1946; private collection, New Hampshire. This watercolor is number four in a print series of six scenes done for Field & Stream titled “Gunning in America.” The figure on the right is most likely the artist with his favorite dog, Chief, at his side. |

When Benson won a cash award in 1893 for an interior scene titled Firelight, he used the money to purchase a rustic hunting camp in Eastham, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where the focus of his oeuvre took a radical departure toward wildfowl. The Farmhouse, as the camp was called, became a frequent background in his depictions of birds in flight over salt marshes (Fig. 2). Benson observed, “Every artist must see things in his own way. He will do this as the Japanese have done it for years—study some object of nature until he can draw it from memory by repeated practice. In that way I learned how birds appear in flight, watching them by the hour, returning to the studio to make drawings, then back to the birds to make corrections.” Later that same year, Benson exhibited a painting of wildfowl, Swan Flight, which sold almost instantly. This sale signaled a turning point in the public’s opinion of sporting art, for Benson’s established success helped elevate bird paintings to a “legitimate” subject matter in the fine arts.

Benson’s sporting scenes—from gaffing salmon on Canada’s Gaspé Peninsula to geese flying over snow-covered Cape Cod marshes—found immense success. During the twenties and into the Depression, Benson’s etchings alone (created in limited editions as opposed to Currier & Ives’ mass-produced prints) earned him about $80,000 per year. His artistic successes subsidized his other passions of duck hunting and salmon fishing. In addition, Benson’s work embodies a sincere appreciation of the great outdoors through his keenly rendered observations of nature’s moods, colors, skies, and patterns.

| |

| Fig. 4: Ogden Minton Pleissner (American, 1905–1983), Clouds Rising, Pinto Lake, The Wind River Range, Wyoming. Signed and dated Pleissner O37. Oil on canvas, 28 x 30 inches. Original hand-carved Newcomb-Macklin frame. Provenance: J.J. Gillespie Galleries, Pittsburgh, PA; private collection, New England. |

The artist A. Lassell Ripley (1896–1969) is another charter member of America’s sporting art fraternity. Ripley, a friend of Benson’s, also attended the Boston Museum School. His landscape paintings and urban Boston subjects won him praise during the Depression; however, like many of his contemporaries, he faced a diminishing market for his impressionistic paintings. Ripley then turned to sporting art and focused on his passion, upland bird shooting (Fig. 3). His first sporting art exhibition at the Guild of Boston Artists was a huge success, cementing his focus on the genre.

In the latter part of the same era, Ogden Minton Pleissner (1905–1983) combined his talent as a great artist with his knowledge and experience as a great sportsman. During the Depression, Pleissner taught drawing and painting at the Pratt Institute. An avid outdoorsman, the artist spent almost every summer for seventeen years in Dubois, Wyoming, at the C-M Ranch. His Western landscapes of the 1930s are considered his first sporting paintings and are still avidly sought by collectors (Fig. 4).

| |

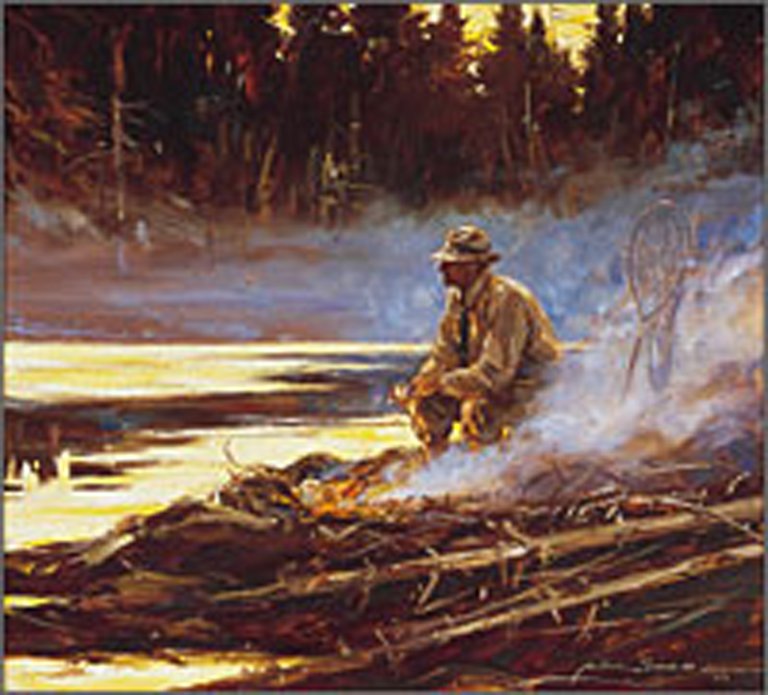

| Fig. 5: John Swan (American, b. 1948), Guide’s Dinner. Signed and dated John Swan ‘00. Oil on board, 12 1/2 x 13 1/2 inches. |

Sporting art—both historic and contemporary—now holds an established position in the American art world. The earlier tradition of commercial illustration and prints generated popular images for the masses. Artists like Tait and Homer bridged the gap when sporting art shifted into fine art circles during Benson’s generation. Today’s collectors see themselves as custodians of a changed, if not vanished part of American history and the natural world.

Collectors’ Considerations

In addition to research into a work of art’s condition, provenance, and market value, the following criteria are useful in making evaluations regarding American sporting art. As a supporting example, I have focused on Clouds Rising, Pinto Lake, a 1937 oil by Ogden Minton Pleissner.

1. Artist

It is important to research how an artist fits into the sporting art field. Many artists who were not known as sporting artists at times depicted hunting, fishing, and field trial scenes. These works can be seen as opportunities to supplement collections. However, significant American sporting art collections are usually built on a foundation of late-nineteenth- to early-twentieth-century artists that include A.F. Tait, A.B. Frost, Frank Benson, Philip R. Goodwin, Winslow Homer, A.L. Ripley, Percival Rosseau, and Edmund Osthaus.

2. Subject Equals Demand

The paintings that will stand the test of time in terms of value and importance are those with subjects that an artist is known for. For instance, a Pleissner fly-fishing scene would tend to attract more attention than would one of driven grouse shooting in Scotland, simply because more American collectors relate to fly-fishing and the artist is known for that subject.

It is wise to do your homework and become acquainted with an artist’s complete oeuvre. An oil on canvas of quail hunting by A.L. Ripley recently shattered the record price for the artist, bringing over $200,000 at public auction, whereas his oil portraits bring under $10,000. Similarly, Pleissner’s subjects range from European landscapes to World War II illustrations done for Life magazine; yet his sporting scenes which are perhaps the most desirable to collectors.

3. Composition and Mood

The overall aesthetic success of a painting is another consideration. Pleissner was a master of composition—every line, angle, and form was placed for a reason. His style is informed by classical traditions including rigorously realistic draftmanship, perfect perspective, and exacting composition, but creating a mood was also a key element of his technique. In Clouds Rising, the beaming light filters down through the clouds, reflects off the mountains, illuminates the mist, and wraps around the lake to the fisherman in the foreground.

The artist’s own words best summarize his style: “A fine painting is not just the subject, not just the article or the image on the canvas. I think it is the feeling conveyed of form, bulk, space, dimensionality, and sensitivity. The mood of the picture, that is most important.”

Suggested Reading:

Virginia Barnhill, Wild Impressions: The Adirondacks on Paper, Prints in the Collection of the Adirondack Museum (Blue Mountain Lake, NY, and Boston: The Adirondack Museum and David R. Godine, 1995).

Faith Andrews Bedford, The Sporting Art of Frank W. Benson (Boston: David R. Godine, 2000).

Warder H. Cadbury, Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait: Artist in the Adirondacks (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 1986).

Stella Walker, Sporting Art (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1972).

Stephen B. O’Brien, Jr., is the owner of Stephen B. O’Brien, Jr., Fine Arts in Boston. He specializes in American, sporting, and Western paintings as well as antique bird decoys and American folk art.

All photographs courtesy of Stephen B. O’Brien, Jr.

This article was originally published in Antiques & Fine Art magazine. Fully digitized versions are available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|