|

| Home | Articles | Prayerful Art/Artful Prayer: The Book of Hours |

|

|

|

|

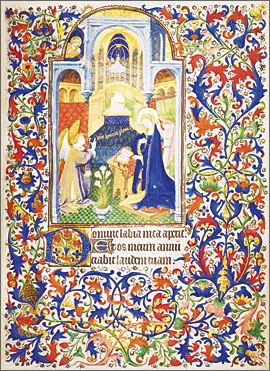

Fig. 1: “Mary of Burgundy at Prayer,” Book of Hours of Mary of Burgundy, by the Master of Mary of Burgundy, Belgium, ca. 1480. Tempera on Parchment, 225 x 165 mm. Courtesy of Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis, 1857, f. 14v.

|

It is hardly surprising that the Book of Hours has been dubbed the late-medieval “best-seller.” Between the mid-thirteenth and mid sixteenth centuries, this devotional book grew in popularity among laymen and -women, who used it to sanctify their days through prayer. The production of Books of Hours, or Horae1, eclipsed that of all other types of books, even the Bible. Initially handwritten and illustrated by scribes and illuminators, they were later printed in well over a thousand editions. Sometimes humble and unillustrated but often elaborately decorated for aristocratic patrons and the well-to-do urban elite, Books of Hours are among our most valuable cultural documents of the late Middle Ages.

For the laymen and -women of the late medieval period, the spiritual life of the clergy was something to be revered and emulated. Through ritual and custom, the Church’s ordained seemingly enjoyed a privileged access to God that was unattainable for many people. Priests, monks, and nuns sanctified time by daily praying the Divine Office, a complex liturgical prayer that frequently varied. The Divine Office was found in the Breviary, a book that contained the daily public prayer of the Church. Breviaries were rarely owned by laymen and -women, for whom the distractions of secular life precluded the regular recitation of such a battery of devotions. Instead, laymen and -women sought a comparable but simpler book that would permit them to imitate the religious experience of the clergy. In the Book of Hours they found a user-friendly prayer book that suited their needs.

|

|

|

|

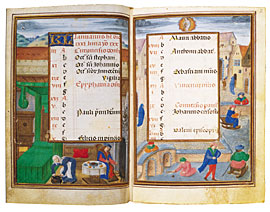

Fig. 2: “Annunciation,” De Levis Hours, workshop of the Master of the Duke of Bedford, Paris, ca. 1410–1420. Tempera and gold on parchment, 216 x 153 mm. Courtesy of Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Ms. 400, f. 23.

|

An illuminated miniature from the Hours of Mary of Burgundy illustrates the purpose of the Book of Hours (Fig. 1) very well.2 Seated within a small oratory, Mary prays from her Horae. Absorbed in prayerful reflection, her finger guiding her reading, she appears not to notice what is taking place beyond her window. There, in a light-filled Gothic church, Mary of Burgundy appears again, this time with her husband and her ladies-in-waiting. They have a private audience with the Virgin and Christ-child. What the artist has captured is Mary’s experience of prayer. The Book of Hours is a vehicle that transports her from a mundane to a transcendent spiritual reality. It is the means by which she communicates directly to the Mother of God, who will listen to her concerns and answer her prayers.

The Book of Hours is first and foremost a volume of Marian devotion. Though no two are exactly alike, at the core of each is the lengthy liturgical prayer called the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, more commonly known as the Hours of the Virgin. Composed primarily of psalms, hymns, prayers, and various pious ejaculations, the Little Office was divided into eight segments known as the “canonical hours.” Beginning at sunrise and continuing at approximately three-hour intervals throughout the day, the clergy was required to recite the Divine Office at the eight “hours” known by their Latin names: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. The Hours of the Virgin were patterned on this ancient form of prayer. Of course, even though the Little Office was much shorter and characterized by far fewer daily variations than the Divine Office, not every layperson would have been able to adhere steadfastly to its regular recitation throughout the course of the day.

|

|

|

|

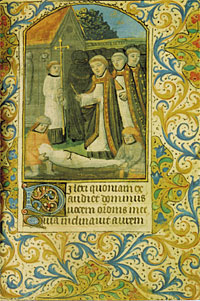

Fig. 3: “January,” Book of Hours for the Use of Rome, Flanders, ca. 1475–1500. Tempera and gold on parchment, 114 x 84 mm. Courtesy of Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Ms. 287, ff. 1v-2.

|

The division of the text according to the canonical hours provided a convenient opportunity for artists to insert illustrations. In many Books of Hours, illuminated miniatures mark the beginning of each hour, acting both as bookmarks in this era before the widespread use of pagination and as visual aids to prayer and devotion. These images often depict in sequence scenes from Christ’s Infancy or Passion. In the De Levis Hours, a miniature of the Annunciation signals the beginning of Matins (Fig. 2). Beneath the image we read the opening lines of the hour: Domine labia mea aperies. Et os meum annunciabit lauden tuam. (Lord, Thou shalt open my lips. And my mouth shall sing thy praise.)

Though they are among the most important flowerings of the late-medieval cult of the Virgin, Books of Hours comprise more than devotions to the Madonna. Most include a variety of prayers that the users could have read separately from the Hours of the Virgin. At the beginning of a typical Horae, the reader would have found a liturgical calendar that indicated the feast days of saints and of the Church. In some of the more densely illuminated versions, the calendars were illustrated with zodiacal symbols and genre scenes depicting activities characteristic of the changing seasons. In a fifteenth-century Flemish Book of Hours, the calendrical text for the month of January seems to float in two panels above larger paintings of which we see only the outer margins (Fig. 3). At left, we find a comfortably appointed interior where a man warms himself by the fire while his wife attends to household chores. The facing leaf depicts an outdoor scene with men entertaining themselves on an icy town waterway.

Four brief Gospel lessons usually follow the calendar, often illustrated with images of the Evangelists in the act of writing. Then comes the Hours of the Virgin, followed by other little “offices”: the Hours of the Cross and of the Holy Spirit, with illustrations of the Crucifixion and the Pentecost. These are succeeded by more prayers to the Virgin known as “Obsecro te” (I beseech thee) and “O Intemerata” (O immaculate Virgin). They are followed by the Penitential Psalms, usually illustrated with an image of King David, and a litany to the saints.

|

|

|

|

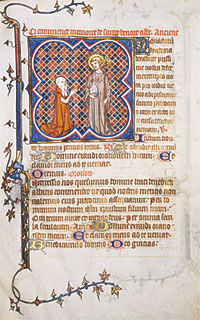

Fig. 4: “Burial.” Connolly Hours, France, fifteenth century. Tempera and gold on vellum. Boston College, John J. Burns Library. Ms. 86–97, f. 106.

|

Near the end of most Books of Hours is the Office of the Dead. This lengthy liturgical office was recited through the night while waking a deceased family member. It was also considered efficacious in decreasing the amount of time that one’s departed relatives spent in the fires of purgatory, and so it was appropriate to pray on a regular basis. A variety of illustrations opens this text. Representative of the group is the burial scene found in the Connolly Hours (Fig. 4).

Finally, many Books of Hours include a number of “suffrages,” or brief prayers, to various saints. These devotions often served practical purposes. For example, Saint Anthony’s intercession could be called upon for skin ailments, Saint Margaret’s for the pain of childbirth. Blanche of Burgundy, the Countess of Savoy, must have recognized the value of this saintly assistance: In the Book of Hours that she commissioned in Paris during the second quarter of the fourteenth century, there is an extensive series of suffrages, each accompanied by a picture of her praying to the different saints (Fig. 5). Blanche of Burgundy is a noteworthy representative of many patrons who, if their pocketbooks allowed, were able to commission customized Books of Hours that were often brilliantly illuminated.

Books of Hours were produced throughout Western Europe. In spite of their significant cost, by the fifteenth century, the demand for them was so great that a system of mass production seems to have been put in place—one could purchase them in bookshops in many of the urban centers in the West. French and Belgian workshops were the most prolific producers of the Horae. Significant numbers of Netherlandish Books of Hours also point to a noteworthy demand in the Low Countries. Although fine examples were produced in Italy, Germany, and Spain, Books of Hours survive in fewer numbers from these regions, where they do not appear to have been as much a part of the culture. It is difficult to accurately gauge their popularity in England, where so many Catholic books were destroyed during the Reformation.

|

With some significant exceptions, most Books of Hours are primarily written in Latin. For their middle-class and aristocratic owners, who by the late Middle Ages were increasingly literate, this fact seems not to have posed a problem. The language was a simple Church Latin, and the prayers changed little. The reader, who might have grown up speaking a romance language derived from the ancient tongue, would have also heard many of the Latin prayers in church, such as the Ave Maria. For those privileged owners of illuminated Horae, the illustrations themselves would have spurred prayer and meditation.

|

|

|

Fig. 5: “Blanche of Burgundy Praying Before Saint Benedict,” Savoy Hours; fragment of the original text. This section attributed to the workshop of Jean Pucelle, ca. 1334–1348. Tempera and gold on parchment, 201 x 147 mm. Courtesy of Yale University, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Ms. 390, f. 7.

|

Today, Books of Hours survive by the thousands in public and private collections. Frequently prized for their luminous paintings, they are part of our cultural patrimony of the late Middle Ages. They are invaluable links to our medieval past and continue to enamor scholars and collectors to this day.

Timothy M. Sullivan is a doctoral candidate in the History of Art at Yale University. A specialist in medieval book illumination, he is co-author of Reflections on the Connolly Book of Hours (1999).

Suggested Reading

De Hamel, Christopher. “Books for Everybody.” In A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. London: Phaidon Press, 1994.

Harthan, John. The Book of Hours. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1977.

Wieck, Roger. Painted Prayers: The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art. New York: George Braziller, 1997.

Wieck, Roger. Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. New York: George Braziller, 1988.

|

|

- The term Horae is derived from the Latin name of the liturgical prayer at the core of the Book of Hours, the Horae Beatae Mariae Virginis, or Hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary. It has also come to designate the entire Book of Hours, and so will be used in both senses in this article.

- Many Books of Hours are known by titles that recall former owners or the benefactors who gifted them to their present library. The name Hours of Mary of Burgundy, for example, was applied to the book because of its original owner, while the Connolly Hours, referenced later, refers to the name of the donor.

|

|

|