|

|

|

|

|

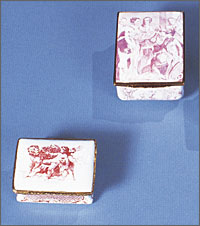

Fig. 1: Two oval patch boxes, Midlands, ca. 1800. The boxes feature themes inspired by the Wilberforce Anti Slavery movement in England.

|

The English fashion for decorative painted enamels spanned nearly a century, from the 1750s into the 1840s. When first introduced from the Continent, their colors, sophisticated designs, and suitability as tokens of affection caught the imaginations of the luxury-minded Georgian elite. Aware of the market potential for these trinkets, English artisans developed an enamel cottage industry that not only rivaled work from the Continent, but achieved a finer quality of craftsmanship. To differentiate between English and Continental enamels, the former are often generically referred to as “Battersea” after the enamel factory located in the Battersea area of London.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 2: Bonbonniere, Birmingham, ca. 1770–1775. In the form of a lady’s French Court shoe.

|

These small, decoratively embellished containers were made for various purposes. The most common are the little boxes used to hold snuff or beauty spots (often applied to cover blemishes and referred to in the period as “patches”) (Fig. 1). Other popular presentation pieces include bonbonniéres (Fig. 2), which held sweetmeats, or hard candies, to sweeten the breath; scent bottles for perfumes; bodkin cases to hold needles; and étuis, containers for useful things that a lady found “necessary,” such as scissors, sewing implements, letter openers, pencils, and pens. Other household objects made of decorative enamel are more unusual. These include writing caskets, candlesticks, inkstands, tea caddies, wine funnels, telescopes, sugar canisters, beakers, and bowls.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3: A rare South Staffordshire “Tussie Mussie,” ca. 1770. These small enamel vases were sewn into the bodice of a lady’s dress for the wearing of fresh flowers.

|

Stemming from a technical heritage that included other methods of enamelwork—cloisonné, champleve, and basse-taille—all of which required metalwork to separate the enamel colors, Georgian painted enamels began with a plain thin copper base coated with a ground glass mixture that annealed when fired and essentially turned into a skin of white glass, over which paint was applied with a brush. This process was most successful on convex surfaces such as small boxes, which were enameled on interior and exterior surfaces to avoid warping.

The earliest English enamels were painted entirely by hand (Fig. 3). This was a time-consuming and tedious task because of the different firing temperatures of the enamel paints, which had to be applied in a specific order relevant to the amount of heat the various colors could withstand. This process was compounded by the difficulty in regulating the kiln temperature, since thermostats as we know them today did not yet exist.

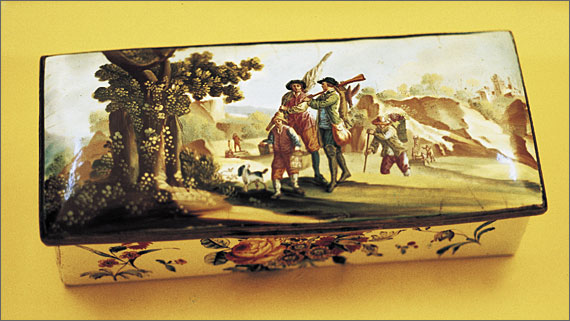

The most important technical improvement the English made to the art of enameling was the process of transfer printing (Fig. 4). Introduced in the mid-eighteenth century, this new technology was more economical for the manufacturer in that it reduced the production time and required less artistic painting. The process involved colored inks that were applied to copper plates engraved in reverse and transferred to thin, glazed paper. The paper was then placed on the white enamel object and fired. The enamel could either be left with just the transfer or the enamel transfer could then be in-painted by adding full color brushwork by hand and refired.

|

|

|

Fig. 4: A large tobacco box, Birmingham, ca. 1770. Transfer-printed and overpainted scene after Tieners painting, The Return from the Hunt.

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 5 (left): York House (Battersea) small table snuff, 1753– 1756, printed in a rare color of red, with a Putto and the British Lion.

Fig. 5 (right): York House (Battersea) table snuff, ca. 1753–1756, transfer-printed in puce by Simon François Ravenet, the engraver, depicting Britannia presenting a medal surrounded by the Arts and Sciences.

|

The most rare and highly sought-after enamels are those produced at the first established English enamel factory, York House (Fig. 5). Located in the Battersea section of London, the factory was established in 1753 and was in operation for only three years before declaring bankruptcy. The factory’s enamels are historically important because York House was the first English company to introduce transfer-printed wares to the London public. Because of their early date and limited span of operation, York House enamels are very scarce, enhancing their desirability. Some York House enamels may be identified by the following characteristics: The transfer prints often feature mythological and biblical themes; their engravings are typically in the “French” or Continental taste (Fig. 6); the ground color is a creamy white rather than a bright white; and the ink colors usually consist of soft tones of red, sepia, purple, indigo, or purplish-black. Also, the engraving is very crisp and of the highest quality; it is never blurred. There are perhaps many other types of enamel that were hand-painted at York House, but they are not as easily identified. As a word of caution, after the York House factory failed, a bankruptcy sale followed and many of the engraved plates were bought by other enamellers and taken to different areas of the country; this resulted in later “re-strikes,” which are less valuable than the early examples made at York House. One can tell the difference by noting the poorer quality and the changes in the shapes of the later objects as they evolved with new fashions.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 6: York House (Battersea) plaque, ca. 1753–1756, The Fortune Teller, engraved by Simon François Ravenet, depicting an old gypsy woman telling the lady’s fortune, while a young boy is stealing the lady’s purse.

|

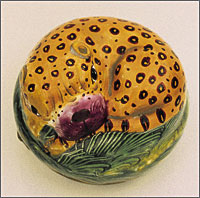

Many small enameling firms were located in the Midlands region of England, such as Bilston, Wolverhampton, and Birmingham. The metal mount-makers also lived primarily in this part of the country, supplying metal bezels and hinges to the enamel artists. Enamels produced in these cottage-industry workshops were decorated with a range of hand-painted and transfer-printed images, from botanical, animal, and genre scenes to favorite mottos of the time. Animal forms (Fig. 7), today called “figurals,” were often products of the Midlands enamellers and are among the rarest and most expensive of all English enamels—probably because they were admired and played with by children, and thus many have not survived intact. Very few English makers marked their enamels, and signed or dated examples are extremely rare.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 7: Bilston snuff box or bonbonniere, ca. 1780. Sleeping leopard curled up on a grassy mound.

|

The interest in enamels produced in England declined in the early nineteenth century, and the demand virtually stopped by the 1830s; the last known English period enamellers ceased production in the early 1840s. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, forgeries of eighteenth-century English enamels began to appear on the Continent. These enamels were made in response to the working classes who wanted what they thought were the bibelots of the Georgian “carriage trade.” The Parisian firm Samson was one of the main producers of these copies, with other companies following suit. These forgeries are poor imitations for the most part and are easily detected when compared to the quality of the originals (Fig. 8).

The revival of the English enamels industry began in the early 1970s. While many contemporary examples are made in the spirit of the eighteenth-century models, few capture the essence of the period enamels. Most of these replicas are clearly marked in the enamel by contemporary makers, which easily identifies the work as new.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8: Two small oval "Motto Patch" boxes. The left example: Birmingham, ca. 1780–1790, transfer-printed and lightly overpainted in translucent color; the right example: a Samson forgery from Paris, ca. 1890–1900. Compare the two: The Birmingham model is printed, the Samson example is painted in imitation of a transfer print; the cobalt blue is almost black on the English example, while the French copy is a modern electric-blue color; the English mount and hinge and the bezel holding the enamel lid are precisely made, the French mount is ill-fitting, and the hinge has a protruding lug which holds the lid open, absent on the English example; the English thumbpiece is a delicate small bit of metal, just enough "lift" to open the top, as opposed to the "cupid-bow lips" type on the Samson, model with its stiff, thick, and clumsy thumbpiece.

|

Modern forgeries are also in the marketplace, sometimes found in the inventory of street vendors in England. These forgeries have the same shapes as period examples yet display clumsy and crude decorative elements rather than the refined and fluid decoration of period examples. Spurious images include American flags on ships, cock-fighting, and wrestling and boxing subjects. The mounts are cheap and artificially aged with acid to make them appear old. The colors are modern shades and garish. At this point, only the hand-painted enamels are forged.

|

When purchasing antique enamels, inquire about the restoration history. Consider the following:

|

|

- A perfect, crack-free object should be examined for authenticity; hairline cracks are a sign of age and should be visible.

- In England today, many antique enamels that display chips are in-painted and sprayed entirely with lacquer. This process not only obscures any restoration, but results in a shiny appearance that looks perfect but is actually restored.

- Remember, enamel is glass—it should be slick and cool to the touch. Lacquer restoration is shiny, but it is neither slick nor cool to the touch.

- Know your dealer or supplier, and get a guarantee and full description on your written and dated invoice.

|

Taylor B. Williams is a partner in Taylor B. Williams Antiques, LLC, Chicago, Illinois, an old-fashioned firm that deals in a full line of antiques, with a specialty in English enamels for nearly 38 years. To learn more, visit www.enamels.com or www.taylorbwilliams.com.

|

|

|