|

| Home | Articles | Artists after Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

|

|

AN EXTRAORDINARY NUMBER OF AMERICA’S GREATEST ARTISTS HAVE TAUGHT OR STUDIED AT THE PENNSYLVANIA ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS IN PHILADELPHIA.

|

|

|

Interior view of the academy’s museum.

The Victorian-Gothic building was built in 1876 by the Philadelphia firm of Frank Furness and George Hewitt. Hewitt was a pupil of William Morris Hunt who introduced him to the aesthetics of the modern Gothic Revival. Both interior and exterior combine influences of the day’s leading designers including John Ruskin’s predilection for the richly colored designs of fourteenth-century Venice, Christopher Dresser’s Eastern-influenced ornament, and Viollet le Duc’s use of foliated decoration with cast-iron architecture. Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

|

Since its founding in 1805, the nation’s oldest art school and museum has been connected to the Peales, Cecelia Beaux (1855–1942), William Merritt Chase (1849–1916), Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), J. Alden Weir (1852–1919), Daniel Garber (1880–1958), and, inextricably, the controversial instructor Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). Many other artists took part in the academy’s influential annual exhibitions (discontinued in 1969), or their works have been collected for the academy’s museum, an unparalleled repository of important American

|

|

|

Circle of Thomas Eakins

Thomas Eakins at Forty, 1884 Albumen print, 8 1/4 x 3 inches. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art

|

works of art that were originally intended for study purposes, but that accumulated into a significant holding.

A century ago, avant-garde movements did not wholly infiltrate the traditional curriculum of the academy. Even with modernists such as Arthur B. Carles (1882–1952) as instructors, academic training methods focused primarily on draughtsmanship, including drawing from live models and the anatomical studies so steadfastly promoted by Eakins. Nonetheless, since 1920 the academy has hosted important exhibitions of modern art, has acquired the work of established and emerging contemporary artists, and has classically trained some of the twentieth century’s leading modernists, including John Marin (1870–1953), Charles Demuth (1883–1935), John Sloan (1871–1951), Robert Gwathmey (1903–1988), and more recently, artist and director David Lynch (b. 1946). |

|

|

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916) Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916)

Starting Out After Rail, 1874

Oil on canvas, mounted on masonite,

21 1/4 x 19 7/8 inches

Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston;

Hayden Collection

In Thomas Eakins: American Realist at the Philadelphia Museum from October 4, 2001, to January 6, 2002. |

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916), The Pair-Oared Shell, 1872. Oil on canvas, 24 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mrs. Thomas Eakins and Miss Mary Adeline Williams, 1929 In Thomas Eakins: American Realist at the Philadelphia Museum of Arts through January 6, 2002.

|

After studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts from 1862–1866, Thomas Eakins was among the first waves of American art students to flock to Paris for training.

|

|

|

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916), Baseball Players Practicing, 1875. Watercolor, 10 7/8 x 12 7/8 inches. Courtesy of Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design; Jesse Metcalf and Walter Kimball Funds In Thomas Eakins: American Realist at the Philadelphia Museum of Arts through January 6, 2002.

|

He studied in the academic tradition at L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, but put a decidedly personal and American spin on his subject matter by depicting sporting scenes of fishing, sailing, rowing, and boxing, such as in his celebrated The Champion Single Sculls (Max Schmitt in a Single Scull).

Recently discovered works by Eakins, along with his famous sporting scenes, moving portraits, controversial paintings of surgeons at work, and explorative studies in all media, are part of the retrospective Thomas Eakins: American Realist at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, October 4, 2001, through January 6, 2002. |

|

|

|

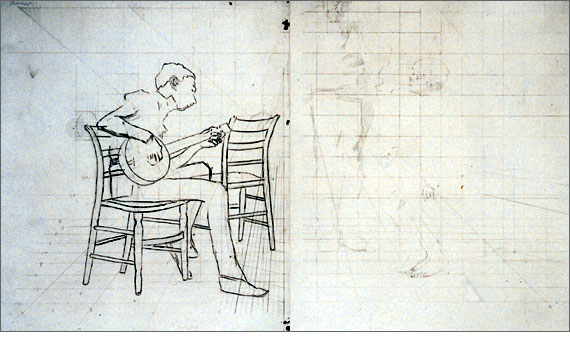

Thomas Eakins (American, 1844–1916), Negro Boy Dancing: Perspective Study, circa 1877–1878. Pen and black, red, and blue ink over graphite on two sheets of foolscap, 17 x 14 inches (each sheet). Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; 1985.68.16.1 & 2

|

As a student, instructor, and director at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Eakins developed and proliferated his own type of realism. His style is characterized by an attention to anatomy, perspective, principles of motion, reflection, and accuracy. By observing living creatures in action as well as dissections and cadavers, Eakins sought to better understand anatomical structures so that his paintings were scientific. He eventually brought cadavers—from human to lion—into the academy’s classrooms.

Eakins made photographic, sculptural, and oil studies of his observations, but drawing remained a preparatory step to his paintings throughout his career. Fortunately, many of his drawings, which serve as records of his creative and scientific processes, were collected by one of his students, Charles Bregler (1864–1958). Bregler remained devoted to Eakins even after his teacher’s 1886 dismissal from the academy for his inflexible teaching methods and insistence on teaching from a fully nude model (dead or alive) even for students only interested in learning to paint landscapes or teacups.

Negro Boy Dancing: Perspective Study is a typical example of Eakins’s “project” drawings. In preparation for finished works, such as his 1878 watercolor depicting an African-American “dancing lesson,” the artist executed perspective drawings to plan spatial effects. Annotations on the drawing allow full understanding of the artist’s perspectival scheme. According to Eakins scholar Kathleen Foster, “the annotations clearly state that the horizon is 48 inches, the viewing distance 4 feet, width of the scene 8 feet, and that the standing man and dancing boy are 5 feet, 7 inches and 3 feet, 11 inches tall, respectively.” From these annotations, we learn that Eakins found measurement of his subjects and pictorial spaces important, and that he positioned himself as well as the viewer as participants in the scene. At a horizon line of 48 inches, Eakins placed his eye at the height of two of the figures in the scene—the guitar player and dancer—who perform under the watchful eye of an elder mentor.

This work is included in the exhibition Process on Paper: Drawings from Charles Bregler’s Thomas Eakins Collection at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, on view at the academy from October 6, 2001, through January 6, 2002.

—Parts excerpted from the exhibition pamphlet, which was written by guest curator Amy B. Werbel, Associate Professor of Fine Arts, Saint Michael's College. |

|

|

|

|

|

Susan Macdowell Eakins (American, 1851–1938), The Tennis Player, 1933. Signed lower right. Oil on academy board, 18 5/8 x 15 inches. Courtesy of Canada Library, Bryn Mawr College In Susan Macdowell Eakins on view at the Woodmere Museum through December 9.

|

In 1876, Susan MacDowell was impressed by Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic, depicting a surgical operation, then on view at the Hazeltine Gallery. The bloody realism of the painting was shocking to most Phildelphians, but inspirational to MacDowell, who decided to study with Eakins. She went on to win the academy’s Mary Smith Prize in 1879.

Following six years of study at the academy, Susan married Eakins in 1884 and thereafter painted only sporadically until the 1920s. She spent much of her time supporting her husband’s career; however, they each maintained a studio within the house. Both Eakins championed a woman’s right to attend life-drawing classes and utilized photography as a preparatory step for their paintings. The modeling of the figure in The Tennis Player exhibits Susan’s study of the human form.

During their marriage, Susan painted in her husband’s sober, realistic style. After his death in 1916, she became much more prolific and adopted a looser, brighter, and more informal technique. Her first one-woman show, a 1973 exhibition at the academy, took place thirty-five years after her death.

The exhibition Susan Macdowell Eakins, on view September 16 through December 9, brings together about thirty of her works and is part of a series of exhibitions titled Passionate Palettes: A Celebration of Philadelphia Women Artists, presented by the Philadelphia Foundation at the Woodmere Art Museum, Philadelphia. |

|

|

|

|

|

| William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916), Spanish Girl (Girl with Riding Crop), circa 1883. Pencil on paper, 12 1/16 x 8 inches. Courtesy of Brock & Co., Carlisle, Massachusetts. |

The influence of the exhibitions held at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts can be affiliated with the work of the renowned New York impressionist William Merritt Chase. When Chase exhibited at the academy in 1879, John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902) showed two canvases depicting urban docks that caught the attention of the press. Perhaps inspired by Twachtman, Chase soon after explored this modern theme of the city waterfront.

Chase participated in annual exhibitions at the academy in 1879, 1880, and 1883. In 1883, about when Spanish Girl was created, the artist garnered critical acclaim at the Paris Salon for out-of-doors European works. He then ceased exhibiting at the academy until 1892, when he began to show his Shinnecock, Long Island, landscapes. Chase taught at the academy from 1896 to 1909. |

|

|

|

|

|

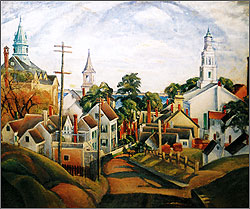

| Nancy Maybin Ferguson (American, 1887–1967), Road to the Monument, Provincetown, ca. 1925. Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Melissa Williams Fine Art. |

As a student at the academy in 1902–1903 and 1907–1912, Nancy Maybin Ferguson (1872–1967) studied under William Merritt Chase. However, by the 1920s Ferguson’s style gravitated toward the fauvist-inspired work of Arthur Carles and other modernists active at the academy.

Ferguson won academy fellowships in 1909 and 1929 and prizes in 1911 and 1916. She was an active member of the Philadelphia Ten, a group of women artists who exhibited together regularly during the 1920s and 1930s. |

|

|

|

|

|

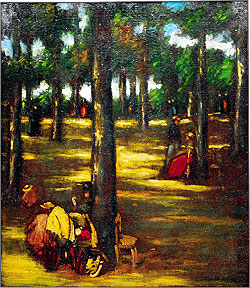

| Robert Henri (American, 1865–1929), Au Bois de Vincennes (At the Forest Vincennes), 1899. Signed lower right. Oil on canvas, 28 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Vose Galleries of Boston. |

Robert Henri trained under Thomas Anshutz (1851–1912) at the academy, but was heavily influenced by Eakins’s focus on realism. However, unlike Eakins, Henri’s approach to realism centered on capturing the emotions and humanity of his subjects. To this end, he painted very quickly, with little attention to anatomical accuracy. His work constituted a spontaneity of feeling in its portrayal of urban, real-life subject matter. In 1908, Henri and other members of The Eight, or Ashcan School of painters, shocked the conservative art world with an exhibition of this new realism. |

|

|

|

|

|

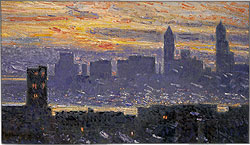

| Childe Hassam (American, 1859–1935), Manhattan Sunset, 1911. Signed and dated lower left. Dated verso with monogrammed initials. Oil on canvas, 19 1/8 x 29 7/8 inches. Courtesy of Spanierman Gallery, LLC. |

Childe Hassam won the academy’s Temple Gold Medal in 1899 for Pont Royal, Paris, a bright Seine view painted from his hotel room window on the quai Voltaire. The academy honored Hassam with the election of Academician in 1906, the Jennie Sesnan Gold Medal in 1910, and the Gold Medal of Honor for lifetime achievement in 1920. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Arthur B. Carles (American, 1882–1952), Venetian Gondolas, ca. 1909. Oil on canvas, 25 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Hollis Taggart Galleries. |

Philadelphian Arthur Carles studied at the academy intermittently between 1900 and 1907 under Cecelia Beaux and William Merritt Chase. A traveling fellowship from 1907 to 1910 allowed him to live in Paris, which at the time was a center for revolutionary ideas springing from the works of Henri Matisse (1869–1954) and Paul Cézanne (1839–1906).

Carles juggled two distinct styles: He painted in a realistic mode, but he also exhibited works in a pioneering style of vivid, fauvist colors and near abstraction. As an instructor at the academy from 1917 to 1925, Carles conducted popular lectures on how to structure a painting through the use of color and was an inspirational force for the younger generation of academy students seeking to explore a more modernist painting idiom. After 1925, having been dismissed from the faculty of the academy, he continued his teaching and his ceaseless experimentation with color. |

|

|

|

|

|

Karen Fogarty, Stalwart, 2000. Charcoal, 31 x 26 inches. In Fifteen Exposures at USArtists. Courtesy of Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

|

Fifteen Exposures, a juried exhibition of works by contemporary academy alumni, is on view October 19–21 at USArtists: American Fine Art Show, 33rd Street Armory, Philadelphia.

|

|

|